|

|

|

|

SYMPOSIUM ARTICLES: Läicité and Secular Attitudes in France Secularism: The Case of Denmark The Secular Israeli Jewish Identity Secularism in Iran: a Hidden Agenda?

|

Secularity in Great Britain By David Voas

What does the term "secular mean in great Britain? Britain is formally a religious country in a way that many modern states are not, having (different) established churches in England and Scotland. The links between church and state have very little impact on contemporary life, however. In some cases they seem to achieve the worst of both worlds, creating an impression that offends one side without benefiting the other.

The term “secular” might for many

people be associated with the mission of the National Secular Society, a

lobby group for church-state separation, which is overtly atheistic rather

than merely opposed to giving religion a

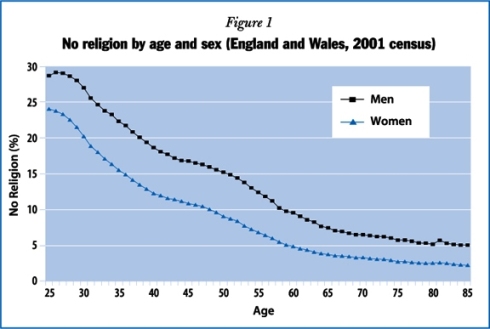

In common usage, though, a contrast is usually apparent between “secular” and “secularism.” “Secular” is the opposite of “religious,” and simply indicates an absence of religious motivation or content (e.g., secular ceremonies, morality, art, etc.). “Secularism” is an ideology that opposes religious privilege and frequently religion itself. Because the British are typically non-religious rather than anti-religious, many people are secular but far fewer are secularists. Unlike Americans, Britons are accustomed to the idea of state-supported religious education, religious broadcasting on network television, bishops in the legislature, and so on. Unlike many continental Europeans, Britons do not tend to feel that they need protection from religious institutions. Indeed, the implicit assumption seems to be that a modest dose of religion is good for people—or at least other people. Social scientific approaches We can describe three distinct though overlapping ways of being secular: not believing, not practicing, and not identifying with a religion. The study of secularity thus raises a double problem: first to try to measure religious (non)adherence, and, secondly, to decide what the results might mean. In our view, identifying with a religion, believing in the supernatural, or attending religious services should not necessarily disqualify someone from being regarded as basically secular. How many people are secular in Britain? The dominant British attitude towards religion is not one of rejection or hostility. Many of those in the large middle group who are neither religious nor unreligious are willing to identify with a religion, are open to the existence of God or a higher power, may use the church for rites of passage, and might pray at least occasionally. What seems apparent, though, is that religion plays a very minor role (if any) in their lives. By contrast, the “Sheilaists” are more conscious of spiritual seeking. “Sheilaism” was the self-applied label used by a respondent (“Sheila Larson”, a young nurse) in Habits of the Heart (Bellah et al. 1985): “I believe in God,” Sheila says. “I am not a religious fanatic. I can’t remember the last time I went to church. My faith has carried me a long way. It’s Sheilaism. Just my own little voice.” Exactly where one should draw the line distinguishing the secular from the rest is unclear. Many nominal adherents are failed agnostics: they used to have doubts, and now they just don’t care. Arguably, most are secular for all practical purposes. If they are included, then at least half the British population could reasonably be regarded as secular. How are secular people different from others? There is enormous variation by age in religious identification. Among people aged 65 and over surveyed for the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey in 2004, only 22 percent say that they regard themselves as belonging to no religion, while 63 percent of young adults (18-24) so describe themselves. These differences might be influenced by life stage (if older people are more religious than young ones), but the evidence suggests that in the main they are generational (produced by a steady decline in religiosity over time; see Voas & Crockett 2005, Crockett & Voas, forthcoming). Exactly half of white men say that they have no religion (in the BSA 2004), versus 41 percent of white women. To put it another way, men make up 58 percent of the secular category as defined above using European Social Survey data, but only 36 percent of the religious groups. Only 17 percent of religious people are not married, widowed, separated, or divorced; by contrast, nearly 40 percent of the secular are never-married. Most, but not all of this effect is explained by age; among those born before 1970, 17 percent of the secular and only 8 percent of the religious are never-married. Likewise, only 15 percent of the religious in that age range say that they have ever lived with a partner without being married, while 38 percent of the secular have done so. Both the religious and the secular are better educated, on average, than those who are neither. (About 30 percent have been in higher education, as against less than 20 percent for the others.) High levels of education often produce scepticism about religion and the self-confidence to be overtly agnostic or atheistic, but higher education is also associated with middle class values, civic participation, suburban living, and other characteristics conducive to churchgoing.

Social and political attitudes The secular are somewhat more likely to appear on the left of a left-right scale (30 percent left vs. 26 percent right), with the opposite true of religious people (25 percent left vs. 31 percent right). The secular are somewhat more likely to say that they never discuss politics; however the statistic is 25 percent vs. 18 percent among the religious. Again, though, only 26 percent of the secular (vs. 37 percent of the religious) say that they have ‘quite a lot’ or ‘a great deal’ of interest in politics. These results hold up even when controlling for age. Conclusion Are secular and religious people in Great Britain different? Yes and no. The age contrasts are significant, with younger, more secular generations gradually replacing those that are older and more religious. At the same time, people who are consciously and consistently religious or unreligious tend to be better educated and in higher occupational categories than those in the muddled middle. Sociologists of religion have tended to concentrate on the core religious constituency, and this conference is a welcome opportunity to examine the opposite pole. Ultimately, the challenge, though, lies in understanding the group in between. When it comes to religion, the British have been ‘puzzled people’ for decades (Mass Observation 1947). Their secularity, like their religiosity, is casual and unconcerned. Britain may illustrate how the secular triumphs: by default. |