|

|

|

|

SYMPOSIUM ARTICLES: Läicité and Secular Attitudes in France Secularism: The Case of Denmark The Secular Israeli Jewish Identity Secularism in Iran: a Hidden Agenda?

|

By Lars Dencik

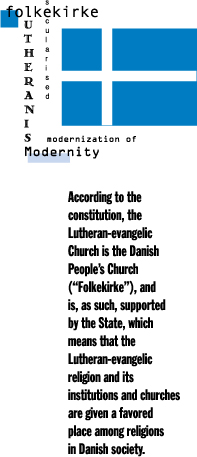

Not only is egalitarianism a highly estimated value in Denmark and in the other Scandinavian countries, these countries also can be characterized by having had-—up to recently—a historically and sociologically extraordinary high degree of ethnic homogeneity. With very few exceptions • all citizens belonged to the same State-run Lutheran church; • all citizens in the country spoke Danish and Swedish, respectively—a language spoken by all inside the country but nowhere outside the country; • all citizens shared the experience and consciousness of a long unified national history. In the wake of modernization, two processes of relevance to our discussion on secularism in society took place: The church as an institution and the influence of religious thoughts on politics and social affairs in general lost influence. Migration and cultural globalization gain influence and affect the fabric of social life in the country. Let me briefly summarize what the State-church system implies: • According to the constitution (§ 54), the Lutheran-evangelic Church is the Danish People’s Church (“Folkekirke”), and is, as such, supported by the State, which means that the Lutheran-evangelic religion and its institutions and churches are given a favored place among religions in Danish society. All tax-paying citizens, regardless of their personal religious beliefs, thus contribute to the priests and bishops of the “Folkekirke.” • Practically all citizens are automatically born as members of the “Folkekirke.” Not to be so demands that the citizens take the initiative to leave the church. At present 83 percent of the Danish population belong to the “Folkekirke.” Denmark, then, from one point of view is clearly a Christian country—as are by the same standards the other Scandinavian countries. This amalgamates into what I for want of a better label would label a secularised Lutheranism as a dominant cosmology in Denmark. Although Denmark (and Sweden) is a country in which most of the citizens by tradition belong to the State church, Christianity as a religion does not characterize the life of any large segment of the population. The number of churchgoers on any regular Sunday is below 5 percent of the adult population and even on the religious holidays (with the exception of the Christmas Eve service) doesn’t rise much above that. A good 80 percent of the population can be characterized as “secular” in the sense that religious practices do not play any part in their daily life. Nor do they to any substantial extent support the Christian-Democratic political party—in Denmark that party attracts approximately 2 percent of the voters in general elections. The paradox, of course, is that still most of the citizens are members of the “Folkekirke.” This fact is used by a majority of the citizens only for entry and exit services—birth/baptism, confirmation, weddings (to a lesser extent) and death/burials. Nevertheless, most Danes’ everyday world view and daily life ethics are profoundly coloured by certain Christian or, rather, Lutheran values: the Protestant ethic of hard work and diligence, combined with a particularly rational way of handling human affairs. In the formation of the modern Danish and Swedish welfare state, this is amalgamated into a “higher” cosmological unity: secularised Lutheranism. In this cosmology, virtually everything is measured according to its utility, nothing is really “holy,” and religiosity is, as I have demonstrated, regarded a question of private inner beliefs. The very categories by which one organizes and evaluates social affairs in Denmark are tinted by the tacit values and viewpoints of secularized Lutheran cosmology. The segment of the population that can be described as “religious” can also be described as, on the average, less educated, more often rurally based, and having a lower income than the secular segment. What constitutes Danishness, and how—if at all—a non-native Dane may achieve that today is a very hot issue in Denmark. During the past two decades, cultural globalization has challenged whatever that, i.e., “Danishness,” has meant to the Danes. In particular, the migration of Muslim groups into the Danish welfare states—today approximately 6 percent of the inhabitants in Denmark are immigrants or children of immigrants, most of them refugees from the Middle East, some of them workforce immigrants from Pakistan—has become an absolutely dominating issue on the contemporary political scene in Denmark. The very phenomenon of culturally “deviant” and, in particular, Muslim presence in Danish society has sharpened the awareness among Danes of their own cultural heritage, life-style, and values. This has meant a sharpened articulation of the secular values modern Denmark celebrates: political freedom, freedom of expression (including the right to criticize and even also to ridicule religious and other “holy” texts and symbols), individualism (also within the family, for instance with respect to children’s rights), and every individual’s right to live according to one’s own individual preferences, sexual liberalism (including relaxed attitudes to homosexuality, to being “daringly dressed” in public, to pornography, etc.), and women’s rights and gender equality in all spheres of life. Not only have these secular values become more clearly articulated than before, they are nowadays also launched, at times aggressively, as values that express the very essence of contemporary Danishness. In Denmark, as in other European countries, the success of what might perhaps be called “traditional secularism,” advocating the independence of politics, education, science, and social affairs from religious dogmas and institutions, has served as a vehicle for emancipation and democracy. The question is: what social role does it serve today, given the context of cultural globalisation and migration and given the content of the secular values advocated as characterizing contemporary Danishness? |

Secularism:

Secularism: