|

|

|

|

SYMPOSIUM ARTICLES: Läicité and Secular Attitudes in France Secularism: The Case of Denmark The Secular Israeli Jewish Identity Secularism in Iran: a Hidden Agenda?

|

Secular Americans:

Freethinkers By Ariela Keysar and Barry Kosmin

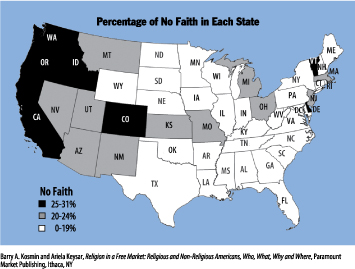

Social surveys have demonstrated again and again that at the beginning of the 21st century the component of the American population that is commonly termed secular is growing in number and as a proportion of the nation. The largest nationally representative survey, the 2001 American Religious Identification Survey of more than 50,000 nationally representative adults, reported that when asked “what is your religion, if any?” 14.1 percent reported they had no religion. When the highly respected General Social Survey (conducted by NORC) in 2004 asked 2,812 respondents “what is your religious preference?” 14.3 percent said “none.” Even the 2005 Baylor Survey, despite its small sample of only 1,712 respondents found that 10.8 percent of the American population was religiously “unaffiliated” according to their definition[1]. Regardless of how we classify these tens of millions of Americans, as non-identifiers with a religion or as non-affiliated with any organized religious group, clearly the secular segment of the population is substantial and has grown considerably since 1990. Secularity takes many forms in American society. Like religion, it varies in intensity along the trajectories of belief, belonging, and behavior. Our recently published book, Religion in a Free Market, shows that the American public does not subscribe to a binary system. In our research, we found self-identifying Catholics and Lutherans who say they don’t believe in God, Mormons who claim a secular outlook, and religious people who, despite their religiosity, are comfortably married to people of other faiths or no faith at all. In America, secularity is one option among many in a free-market-oriented regime that has operated for two centuries. The boundaries between religion and secularity, and among different religions, are not clearly fixed because, to quote from Religion in a Free Market, “the government has found it is not equipped or inclined to provide a precise definition of what constitutes a religion or religious belief or practice. . . .This laissez-faire attitude by the state means there is plenty of organized religion around for Americans to consume and numerous options and places to do so.” [2] Secularity and secular people in America have gone largely un-researched until now. Manifestations of secularity are difficult to distinguish and isolate in the United States because people are not compelled to opt into or out of “religion.” Many countries still operate either legally or in practice under a binary system that offers very limited choices between a monopolistic supplier of established religion and outright irreligion. In contrast, in a free market, secularism and manifestations of secularity can take both positive (pro-secular) and negative (anti-religious) forms. It can offer a range of alternative non-theistic belief systems as well as levels of irreligion and indifference to religion across the realms of belonging and behavior. Thus, in the United States, we can observe populations of secular people of different types, sizes and proportions according to the variable or issue being examined. Secularization among the American public is best measured along three dimensions, the so-called 3 B’s: belief, belonging, and behavior. Each dimension contributes to our understanding of secularization because the three are by no means strictly collinear: Americans who appear to be secular by belief may appear religious by belonging, or vice versa. Others may appear religious by belief and belonging, but not by behavior. And so on. How Big Is the U.S. Secular Population? The actual size of the secular population is open to interpretation according to the criteria one considers relevant for measuring or identifying secularity among the public. It can be claimed to be anywhere from 1 percent to 46 percent of Americans according to whether the criteria are strict and limited to atheists and agnostics or inclusive of anyone unaffiliated with a religious congregation. One obvious social manifestation of secularity is being distant from or out of touch with religion. This can be measured by a lack of affiliation with organized religion. The causes or reasons for this unwillingness or inability to “belong” can vary widely from ideological attitudes to physical access issues. Nevertheless, the actual population of those who do not presently “belong” to a religious congregation or institution is very large. ARIS found that 46 percent of American adults or nearly 100 million people did not regard themselves as or claim to be members of a religious group in 2001. An alternative measure of “belonging” with which to identify the non-religious population is the response to the key ARIS question on religious identification, what is your religion, if any? The responses that we categorized as “No Religion” amounted to 14 percent of the national adult population or 29.5 million people. The most common “secular” response, given by 13 percent of the population, was “None.” An additional 1 percent offered a “positive secular” response. The actual estimates were 991,000 Agnostics, 902,000 Atheists, 53,000 Secular (so stated), and 49,000 Humanists. In addition, over 5 percent of the sample, amounting to over 11 million adults, refused to answer the question. As we state in our book, there are indications to show that this group was mainly irreligious; certainly it did not feel a compelling need to assert a religious identity. This means we can identify a “No Faith” population of adults who either professed no religion or refused to answer the question amounting to 19 percent of adult Americans or over 40 million persons. The accompanying map clearly illustrates that there is a regional dimension to this social phenomenon.

If one counts as seculars those who have a secular or somewhat secular outlook and say they have no religion, then more than one in five adult Americans can be included. That amounts to around 46 million individuals. Interestingly, some corroborating statistics for the size of the secular population have recently appeared in a Gallup Poll on attitudes to the Bible. It found that 19 percent of Americans thought the Bible was a “collection of fables.” Who Is the Archetypal Secular American? An interesting socio-demographic profile or typology of the “classic freethinking American” emerges when we look across a range of variables to search for those most associated with the No Religion identity category and the secular outlook population. This population is more male than female. It is young: the most common age category is 18-35 years. It is more likely to be never married. Among ethnic groups it is more Asian than the general population. Geographically, it is more western. So the picture that emerges is that of a young, never-married, Asian male living in, say, Washington State. That description brings to mind somebody working for a high-tech corporation. Social and Political Implications In Religion in a Free Market, we demonstrated how in the civic realm the seculars have distinct political loyalties. They have a strong tendency to be politically independent of the two main parties. Thus, their reluctance to join or identify with institutions holds for both religious affiliation and political party. If the young cohorts maintain their religious preferences as they get older, it could have major consequences for societal and political issues that are at the heart of current debates within the U.S. society. Since there is more consensus today on economic issues, as regards the virtues of a capitalist economy than there was for instance in the 1930s and 1940s, there is now less class politics. As a result, “values” are the new battlefield, and the religious divide is more central to politics. This is particularly so where ethical or moral issues are involved, such as stem cell research, science teaching, assisted suicide, homosexual marriage, the death penalty, and gun control. One consequence of a free market in beliefs and ideas is a proliferation of choices, as a result of which people will distribute themselves across a wide range of possible options. Unlimited and unregulated options will inevitably give rise to the complexity we have observed regarding the multiple dimensions of secularity and secularism. In a free society, freethinking stretches into all spheres of existence and reduces the pressure to be logical and consistent in opinions or behaviors. This makes delineating the boundaries among secularism, religion, and spirituality very difficult to categorize and measure. Indeed, without any obligation to be coherent and follow normative patterns, some people will exercise their choices in idiosyncratic ways. In his Wealth of Nations, the 18th century free market economist Adam Smith postulated that just as with tangible goods in the economy so in a “natural state” of religion there is no fixed limit to the number of suppliers or their ability to formulate and offer philosophies, religious culture, and spiritual goods and services.[3] And so, today, in America, there is no limit on the ways in which the sovereign consumer can and will reformulate or consume ideas, loyalties, and rituals. This situation is an essential marker of secularization. An environment that offers freedom to exercise liberty of conscience and the pursuit of personal happiness is an important legacy of secularism in the political domain. 1Given the 4 percent margin of error for the Baylor University survey, there is no statistical difference from the ARIS and GSS estimates. 2Barry A. Kosmin and Ariela Keysar, Religion in a Free Market: Religious and Non-Religious Americans, Who, What, Why and Where, Paramount Market Publishing, Ithaca, NY, 2006 p. 7. 3Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Book Five, Chapter 1, Part 3, Article III, The Modern Library, New York, 1965 [1776]. |