|

|

|

|

SYMPOSIUM ARTICLES: Läicité and Secular Attitudes in France Secularism: The Case of Denmark The Secular Israeli Jewish Identity Secularism in Iran: a Hidden Agenda?

|

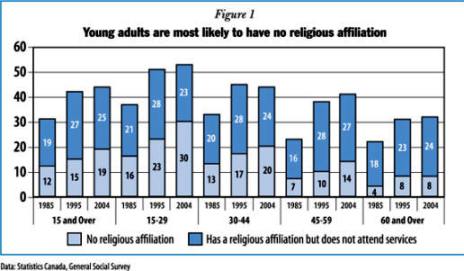

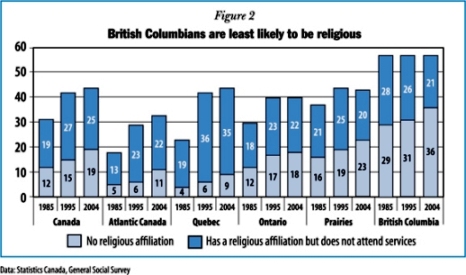

Is anyone in Canada secular? A facetious question. Obviously the answer is yes, but exactly how many is difficult to determine. There are two problems inherent in the question. A great deal depends, of course, on what one means by “secular,” a problematic term inextricably bound with 19th-century ideology. The second problem is that Canada is paradoxical. On the one hand, self-identification with a religious organization is very high, and “belief” in God is even higher. On the other hand, few Canadians attend a place of worship regularly, and religion is conspicuously absent from most of public life today. Until the 1960s, however, the Dominion Census or Statistics Canada did not allow a response of “no religion.” Since then, the “religious nones” have grown from 4 percent in 1971, to 7 percent in 1981, 12 percent in 1991, and 16 percent in 2001. The GSS puts the figure at 19 percent of Canadians over 15 in 2004 (see Table 1). In addition, 25 percent of Canadians reported they had not attended services in the previous year, up 5 percent in the past two decades. People in these two categories are disproportionately young (see Figure I), disproportionately live in British Columbia (see Figure II), and are more likely to be native born Canadians than immigrants, or if an immigrant, to be from China or Japan. In part, the low levels of affiliation in British Columbia are affected by the disproportionate numbers of immigrants who are from China and Japan in the greater Vancouver area. Also, note the anomaly in Quebec, which in 2004 had the largest number of people who never attend services (35 percent), but the lowest number of people who claim “no religion” (9 percent).

Secular or Disembedded? The argument that religion is declining is hard to sustain, when eight of ten Canadians self-identify with a religious group, even if only three in ten attend services regularly. Attendance decline leveled out a decade ago, and Bibby reports that a rebound has begun. Private religious practices are widespread. And of the nearly 20 percent of Canadians who say they have no religion, 40 percent say they believe in God, a third engage in private religious practices, and two-thirds eventually reaffiliate with a church. The number of people in Canada who would fit the “classical” definition of being secular is quite small. A concept which I think better describes the Canadian situation is what Anthony Giddens and Charles Taylor call disembedding. The Canadian data indicate that cultural boundaries are being redrawn, and the nature of religious practices has changed. Canadians are less embedded in their religious communities, but a large majority of Canadians seems to be unwilling to abandon its religious identity. Individual spirituality, a good deal of it eclectic, has become more important, and large numbers of Canadians engage in private religious practices. Canadians have not abandoned the church, but what they want from it has changed. Most people want the church to provide rites of passage and a holiday experience, many still look to it for meaning and spirituality, but few are any longer committed to the church as a total life style. What at one time may have been considered normative behavior, such as weekly attendance, is now a virtuoso performance. These changes in religious behavior have consequences for the organizational and institutional dimensions of religion as well. The church is no longer the center of the community, nor is it the sole arbiter of morality or legitimacy. Many churches, whose top-heavy structures have been slow to adapt, now face financial problems. But change is not the same thing as decline. |