|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links: Articles in this issue:

From the Editor:

Downplaying Religion |

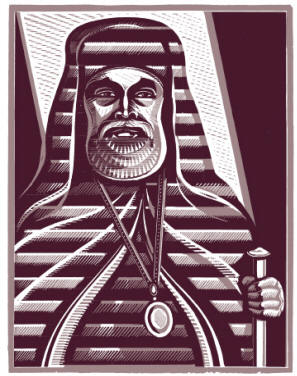

Euphoria in remarkable degree greeted the November 12 election of Bishop Jonah Paffhausen as the leader of the Orthodox Church in America at a church conclave in Pittsburgh. “Hundreds of clergy and laity of the Orthodox Church in America wept for joy yesterday,” Ann Rodgers of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette opened her story on the event. “This is a miraculous occurrence,” the Rev. John Reeves, an OCA pastor in State College, Pennsylvania, told her. We hear stories like this in the lives of the saints.” Press critic Terry Mattingly called it a “stunning, amazing” story in his blog Get Religion on November 13. For Mattingly and others, part of the news value of the event involved the election of the first non-“cradle Orthodox,” or convert, to lead one of the nation’s major Orthodox jurisdictions. Part had to do with an electrifying, impromptu speech Paffhausen had given a few days earlier at the Pittsburgh All-American Council, which had been called to elect a new metropolitan, or primate, for the church. But most of the giddiness bubbled up from an unanticipated outbreak of hope that the OCA might finally escape a grinding decade of squalid scandal that has discredited virtually all of the church’s leadership on charges of financial corruption or collusion to cover it up. It is hard to think of a church scandal that has involved so large a proportion of a significant church’s leadership—not that many American journalists have noticed. Paffhausen’s predecessor, Metro-politan Herman Swaiko, a 75-year-old who ruled with an iron first, had been chased out of office in September after the publication of an internal investigation that, in the words of the October 21 Christian Century, “confirmed accusations that church leaders had either ‘squandered’ millions of dollars or participated in covering up the diversion of funds for personal expenses and to cover shortfalls.” Some of the diversions were little short of humiliating for a church—including the pocketing of funds raised for the relief of 9/11 survivors and an attempt to do the same with funds raised for the families of the children killed in the 2004 school massacre in Beslan, North Ossetia. The scandal began in the mid-1990s with the transfer of several million dollars in grant funding from the Archer Daniels Midland Foundation to unaudited discretionary accounts controlled by the OCA’s then-Metropolitan Theodosius Lazor and its chancellor, the Rev. Robert Kondratick. Denials, cover-ups, and efforts to suppress dissent began in the late 1990s. The cover-up finally began to unravel in late 2005, when a former church treasurer made public charges and a lay organization crystallized “to inform members of the Orthodox Church in America (OCA) of the origins, nature and scope of allegations concerning financial misconduct at the highest levels of the central church administration,” mostly by launching a web operation called Orthodox Christians for Accountability, www.ocanews.org. When the 49-year-old Paffhausen was elected Archbishop of Washington and New York and Metropolitan of All America and Canada, he was the only OCA hierarch untouched by the scandal (among nine sitting and three retired bishops). Nonetheless, his election was unexpected because he had only 12 days before been consecrated as an auxiliary bishop, serving until then as abbot of a small monastery in Manton, California. “We have to work together with one mind and one heart and one soul, striving with all our might to bear witness to Jesus Christ and the Kingdom of God,” Paffhausen said after his election. “Nothing else matters.” Rodgers reported that support for Paffhausen was galvanized by his responses to questions at a public forum that included “forthright admission of wrongdoing at headquarters” and words that clergy and lay delegates accustomed to episcopal claims of unilateral authority longed to hear from one of their bishops: “Authority is responsibility. Authority is accountability. It’s not power.” Paffhausen’s speech “changed the equation,” said Mark Stokoe, the Dayton, Ohio, layman who edited the ocanews.org operation and was the most visible leaders of a long campaign for reform and accountability. “He spoke intelligently, forthrightly, and directly.” Until that point, reformers had been hoping to elect Archbishop Job Osacky of Chicago, a longtime bishop who was involved in the initial cover- ups but who had become a lonely voice for change on the church’s governing Holy Synod. In late 2005, Osacky wrote a letter, later made public on ocanews.org, asking his colleagues whether the former OCA treasurer’s allegations “are true, or are they false?” After that, his Diocese of the Midwest became the only OCA jurisdiction where clergy and laity could speak and organize publicly to demand information about the scandal, without fear of hierarchical retribution. Despite dragging on for years and offering numerous juicy examples of clerical greed and malfeasance, the scandal attracted relatively little news coverage. Some of this is just business as usual—the Orthodox don’t cut much of a figure on the American religious scene, divided as they are into a cluster of small ethnically derived jurisdictions and scattered thinly across the landscape. The Post-Gazette’s Rodgers produced several stories after the scandal exploded, as did the Washington Post’s Alan Cooperman when he was on the religion beat in 2006 and 2007. The Washington Times also produced serious coverage, especially of the most recent phase of the scandal. Finally, the Anchorage Daily News provided what was probably the best and most enterprising coverage of a related scandal, or perhaps sub-scandal, involving the local OCA bishop, Nickolai Soraich of Sitka and Alaska, who was active in the synod’s attempts to suppress investigation of the national scandal. Nickolai also had complex conflicts with his own flock, especially the Aleuts, Eskimos, and Native Americans who make up the bulk of the OCA’s Alaska members. In 2008, Nickolai was relieved of his post by the synod in the wake of a public rebellion of most of the priests in his diocese and scandals involving public drunkenness and alleged sexual harassment by his chancellor, and the bishop’s decision to ordain a convicted sex offender to a minor clerical office. If professional journalism played a minor role in the OCA story (much smaller than in the widely covered controversy in the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America in the late 1990s), cyberspace glowed. The ocanews.org website developed into a huge agglomeration of documents, reports on developments, and commentary from a cadre of anguished laity and priests, many of whom were reluctant (especially priests fearful of hierarchical retribution) to sign their contributions. As editor, Stokoe, who has a long record of OCA activism and served intermittently on its metropolitan council, strove for a trenchant but even-handed tone, while pushing an agenda of vigorous investigation and transparency. The scandal, as laid out in a special investigative committee report published on September 3, began as early as the late 1980s, when the central administration of the perennially cash-starved jurisdiction, based in Syosset, New York, on the north shore of Long Island, began cutting financial corners, moving cash around, and “borrowing” from restricted funds and special charitable appeals and bequests. During the 1990s, the bulk of $3.575 million in grants from the Archers Daniels Midland Foundation and the Dwayne Andreas Foundation, were siphoned off into three unaudited, undocumented, discretionary accounts controlled by Theodosius and his chancellor, Father Robert Kondratick. At least another million disappeared from OCA accounts in the 2000s, but record-keeping has been so poor that the full extent of the misappropriations and fraud will never be known. “The overwhelming evidence shows that the OCA’s leadership at its highest levels have been complicit since as early as 1989 and has squandered millions of dollars,” the report, prepared by a committee of five members appointed by the church in the fall of 2007. “Some placed their personal gain above their Christian duties. Others failed in their fiduciary responsibility to bring these matters to light and correct them.” “The preponderance of evidence clearly shows Metropolitan Theodosius, Metropolitan Herman, the Holy Synod, the Metropolitan Council, the Administrative Committee, the former Chancellor, the part-time Treasurers, and the Comptroller had varying and sometimes multiple roles in this tragedy.” By most accounts, the central figure in the scandal was Kondratick, the church’s chief administrative officer from the late 1980s until 2006. Along with diverting large sums for unauthorized personal and family use, pressing for reimbursement for undocumented credit card expenses, creating a chancery culture of “deception, deceit and covertness,” Kondratick “used OCA resources to develop personal loyalty, dependence and silence on the part of the hierarchy, clergy, and laity through gifts, which included cash, jewelry, meals, travel, lodging, and incidentals,” according to the report. After describing Metropolitan Theodosius as a lazy, hands-off manager who shied away from tough problems, the report argued that “given Metropolitan Theodosius’ style, there was a leadership vacuum, which Kondratick filled as Chancellor. Metropolitan Theodosius’ weaknesses and disinterest allowed the former Chancellor to take almost complete control of Chancery operations, to include staffing, budgeting, and spending decisions. Ultimately, the Chancellor was able to control the Holy Synod, Metropolitan Council, and Administrative Committee.” By the late 1990s, it was becoming difficult to keep the lid on the central administration’s cash diversions, because independent accountants were refusing to audit books to which they had only partial access. The church’s audit committee had began to complain as early as 1993, but was thwarted by Theodosius and Kondratick. The church’s treasurer, Deacon Eric Wheeler, who initially collaborated with the pair, began trying to block and reverse their practices. In the fall of 1999, he was fired as treasurer and given a severance package that required him to remain silent. Jonathan Kozey, the lay chair of the audit committee, was also removed. Archbishop Herman Swaiko, then of the Diocese Eastern Pennsylvania, was appointed Temporary Treasurer and had already been fully briefed by Wheeler about the improprieties in the central administration. Rather than investigating the charges and raising the alarm, Swaiko began a steady campaign to suppress investigation and even discussion of the problems that would last until things began to unravel in 2006. When Herman became metropolitan in 2002, he reappointed Kondratick as chancellor and reappointed him in 2005. As for the other bishops sitting on the Holy Synod, the report concluded that, “in this unprecedented scandal of the OCA, none of the hierarchs, when confronted with information from whistleblowers and others about the financial abuses, took immediate action. It was over the “Beslan matter” that the synod’s unity began to unravel. During the fall of 2004, OCA parishes had raised about $90,000 on behalf of the survivors of the Beslan hostage disaster, when several hundred Russian schoolchildren died after being taken hostage by Chechen terrorists. The money was transferred to the OCA’s “representation church ” in Moscow, a kind of embassy operation for liaison with the Russian Orthodox Church. The SIC report noted that Kondratick had instructed Archimandrite Zacchaeus Wood, pastor of St. Catherine’s Representation Church in Moscow, that he “expected to divide the Beslan funds with Zacchaeus 50/50 and to receive his share in Moscow.” Kondratick apparently expected to use the money to pay the costs of an OCA delegation visit to Russia. Wood consulted with Archbishop Osacky, “who advised him to give the funds to the Beslan charity.” The archimandrite then videotaped a meeting at which Kondratick demanded his half and then showed the video the next day to Metropolitan Herman and “related these events” to three additional OCA hierarchs then visiting Moscow. Osacky apparently sent Herman a full copy of the video, and became the first hierarch to begin to push for a full accounting of the church’s financial records. When Osacky’s diocese demanded better accounting at the church’s next All American Council in June 2005, Herman sent him an angry letter: “I am dismayed and deeply saddened that a member of the Holy Synod would undermine the Holy Synod’s dignity and authority by suggesting that its stewardship is less than responsible or appropriate.” In October, former treasurer Wheeler wrote to the Metropolitan and Holy Synod to report allegations of “massive financial improprieties during his tenure as OCA treasurer.” In November, Wheeler wrote a second letter, and then released it, along with a cache of documents to the public. By January, ocanews.org was up and running and, by February, stories with headlines like “Accusations of Misused Money Roil Orthodox Church” were appearing in places like the Washington Post. On March 18, the Post’s Cooperman reported that Metropolitan Herman had abruptly fired Kondratick and “brought in an independent law firm to conduct a full investigation.” According to Cooperman, “senior clergy and lay leaders across the country had demanded an investigation and eight Orthodox Christian lawyers wrote a letter last week warning church leaders that they could face legal consequences if they did not act soon. But the sudden dismissal of Chancellor Robert S. Kondratick, the church’s chief administrative officer for the past 17 years, surprised even insiders at the denomination’s headquarters.” Metropolitan Herman struggled mightily to keep the investigations and audit under his control, while (along with some other diocesan bishops) ordering his priests to be silent about the scandal. Other members of the synod, especially Bishop Tikhon Fitzgerald of the Diocese of the West, took to the Internet to defend Kondratick and attack Archbishop Osacky and Orthodox Christians for Accountability. At ocanews.org, a continuing rumble of complaints focused on Metropolitan Herman’s refusal to say much about the scandal or to promise full disclosure of the audit or investigation results, especially after it became clear that the metropolitan had arranged for the New York law firm of Proskauer Rose to report to himself, rather than publicly to the church’s metropolitan council. In March of 2007, prompted by the conclusion of the Proskauer investigation and one by an internal subcommittee of members of the council, the synod suddenly shifted course. “It must be confessed that during early 2006, there were many of us who believed that the allegations were exaggerated, motivated by the personal animosity of the accusers, or that there were simple explanations to these misunderstandings,” the statement said. “In March of 2006, it became apparent to us that we were wrong in these beliefs, and that there was substance to at least some of the claims.” When Proskauer delivered an oral report on its findings, the synod admitted that the “body of evidence that was presented was detailed and quite frankly, shocking. The confirmed instances of the abuse of Church trust were determined to be centered on one person, the former Chancellor of the Church.” The synod quickly moved to conduct an ecclesiastical trial, and it eventually voted to defrock the uncooperative Kondratick in July. For his part, Kondratick argued that he was being set up as the fall guy. Although stripped of the priesthood, he remained (and remains) an employee of Holy Spirit Church in Venice, Florida, a position to which he was appointed by Bishop Royster of the Diocese of the South. But Metropolitan Herman balked at releasing either the Proskauer report or that of the investigative committee chaired by Archbishop Osacky—pulling that report from the OCA’s website after an hour. He then moved to dismiss layman Lewis Nescott, a federal prosecutor and a member of both the investigative committee and the metropolitan council, for insubordination. In response, the Diocese of the Midwest and some parishes from other parts of the country began withholding contributions, deepening the OCA’s chronic fiscal woes. One piece of depressing information shaken loose during the scandal was that the OCA, which had consistently claimed a membership of 1 million, actually had only 27,000 dues-paying members. In the middle of all of this, the Rev. Thomas Hopko, the retired dean of St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary in New York, released a glum “reflection” on ocanews.org that gave some insight into the quandary would-be reformers faced, locked as they were into an ecclesiastical system where the hierarch holds all the cards: “We can obey our leaders who disagree with us, and refuse to meet with us and speak with us, to the extent that they do not lead us into heresy or immorality, whatever they are doing, or not doing, in their personal lives and pastoral actions.” At this low point, blogger Rod Dreher, a columnist for the Dallas Morning News and a fairly high profile OCA covert who left the Roman Catholic church because of the sexual abuse scandal of the early 1990s, admitted that he couldn’t bring himself to face up to the current OCA scandal. “There’s a big financial scandal in the Orthodox Church in America and I have deliberately avoided getting too involved with learning about it because I know from hard experience that that sort of thing is a spiritual and emotional trap for me,” Dreher wrote. Others, however, persevered. In late 2007 and 2008, much of the OCA energy was taken up by the Alaska sub-scandal. But Herman felt enough pressure in the fall of 2007 to appoint a second investigative committee, this time chaired by Bishop Benjamin Peterson, who had replaced the retired Tikhon Fitzgerald as the leader of the Diocese of the West. Significantly, the group included priests like John Tkachuk of Montreal and Philip Reeves, who were well known reformers. Under growing pressure to adopt administrative “best practices” and surrounded by a new team of administrators, Herman had more and more trouble squelching dissent. Bishop Nickolai of Alaska was finally deposed in May of 2008, after several fits and starts and a lot of embarrassing public tumult. The bishops of the synod had also been pressed into scheduling an emergency All American Council in November to discuss the scandal and church finances. Preparations for that revealed the depth of rage in the parishes. A series of eight “town hall meetings” was called to discuss plans for the council. All eight were well attended by angry clergy and laity. “It is time to rip off the band-aids and expose the wounds,” Mary Sporcic said at the July 23 meeting in Hartford. “We have been given promises of reports, delays, etc. Take care of the problem! Enough is enough! Time to clean house!” Calls for Metropolitan’s Herman’s resignation or removal occurred at almost all of the meetings. On August 30, the synod, having read a summary of a second investigative committee’s damning report, issued a humbling statement: “Recognizing our weakness, and our failures, the Holy Synod of Bishops bows low before the clergy and the faithful of the Church, and we ask forgiveness from you all. We are truly sorry that this could come to pass in the Church, and that this has happened under our supervision.” On September 3, Metropolitan Herman refused to attend the meeting where the investigative report was to be released and requested a medical leave, which the synod denied. On September 4, he retired. This was not the way things were supposed to go for the OCA. More than any other Orthodox jurisdiction, it had a special sense of mission about life in America and a vision for what American Orthodoxy could be. Planted by Russian missionaries to Alaska in the late 1700s, for much of its history it was, like other Orthodox jurisdictions, mostly a haven for immigrants in a new land. But, in the decades after World War II, its leaders laid out a vision of transformation into a genuinely American church—post-ethnic, using English, establishing a cloud of small mission churches, openly seeking converts, and struggling to build an organizational structure that balanced “American” voluntarist and democratic impulses with the hierarchical traditions of Orthodoxy. During the years of communist domination of Eastern Europe, it was the OCA’s intellectual leadership—theologians like George Florovsky, Alexander Schmemann, and John Meyendorff—who shaped a cosmopolitan church and spoke for all of Orthodoxy on the world stage. In the 1970s, the Moscow Patriarchate made the OCA the first “autocephalous,” or fully self-governing, Orthodox jurisdiction in America. While this status wasn’t recognized by other Orthodox churches here, it made a powerful statement about the Orthodox tradition’s movement into America. But while the OCA did gain many converts, it did not grow, shrinking by more than 50 percent since 1970. Further, the church’s bishops worked to undercut lay and clerical participation in governance in the name of authentic Orthodox ecclesiology. (The OCA picked a new metropolitan three times between 1967 and 2003, and each time, the candidate selected by majority vote of the clergy and laity representatives at an All America Council was rejected by the bishops in favor of their own choice.) However, the activists at ocanews.org showed themselves to be true believers in the OCA’s “American” vision. They demanded institutional transparency, open accounts, servant leadership, and less emphasis on gaudy display. In September and October, the site lobbied hard against selecting a bishop tainted by the scandal as metropolitan, and even against a campaign orchestrated by the influential faculty at St. Vladimir’s Theological Seminary to elect a Russian Orthodox bishop serving in Austria, on the grounds that the OCA must have an American leader. That’s what led to the election of Bishop Jonah Paffhausen, a man described in a headline in the Abilene, Texas Reporter-News as “a baby bishop in a hot seat.” Paffhausen is a shining example of a certain sort of American Orthodox in this time—an intellectual who converted in college because of theological reading. Julia Duin of the Washington Times, the first secular reporter to produce a profile of Paffhausen (on December 1), quoted Father Steven Kostoff’s blog from the council where he elected to explain the dramatic choice: “The black hole of our scandal was sucking the life out of the OCA,” Kostoff wrote. “The election of an untainted candidate with a good reputation now seems like not only a brilliant and spontaneous response by an alert body, but the work of the Holy Spirit.” Paffhausen himself explained the scandal this way: “A lot of it was growing pains, moving from an old-style centralized church into a 21st-century church conscious of itself as a nonprofit that has to abide by normal modes of operation.” Previously, “what the bishop wanted, the bishop could do without checks and balances.” If that attitude sticks, this will be a new day in the 2,000-year-long history of Orthodoxy. But it is by no means clear that the rest of the Orthodox church—in the United States, let alone the rest of the world—is with the program. |

Scandalous

Days in the OCA

Scandalous

Days in the OCA