|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links: Articles in this issue:

From the Editor:

Downplaying Religion |

No Saints Need

Apply It was clear from the outset that Mitt Romney would have a problem with evangelicals—or, more precisely, with the Republican Party’s evangelical base. The antipathy of evangelicals to Mormons is an old and familiar journalistic storyline. One of the more notable recent examples of it occurred in 1997, when the Southern Baptist Convention held its annual meeting in Salt Lake City. The entire corps of religion reporters showed up for an expected donnybrook—which, of course, never materialized, because everyone was very polite, especially the Mormons. In the 2008 campaign cycle, Amy Sullivan was first out of the blocks with “Mitt Romney’s Evangelical Problem,” a September 2005 Washington Monthly article whose subhead said it all: “Everyone wants to believe the Massachusetts governor’s Mormonism won’t be a problem if he runs in 2008. Think again.” In due course, there were data to back her up. According to a September 2007 Pew survey, 39 percent of white evangelicals confessed to having unfavorable opinions of Mormons, as opposed to 46 percent who said they had favorable ones. This compared to unfavorable/favorable numbers of 21-62 and 21-59 among white mainline Protestants and Catholics, respectively. Likewise, a poll conducted a couple of months later by political scientists at Vanderbilt showed that evangelicals viewed Mormons with much greater hostility than any other American religious group—as much as they reserved for atheists. As with the anti-Catholic “whispering” and “underground” campaigns against Al Smith in 1928 and John Kennedy in 1960, evangelical hostility remained for the most part sub rosa. But at least one prominent evangelical pastor, Robert Jeffress of Dallas’ famous First Baptist Church, weighed in, not against voting for a Mormon per se but against imagining that a vote for a Mormon would be equivalent to voting for a “Christian.” “It’s a little hypocritical for the last eight years to be talking about how important it is for us to elect a Christian president and then turn around and endorse a non-Christian, Jeffress told the Dallas Morning News on October 18, 2007. “Christian conservatives are going to have to decide whether having a Christian president is really important or not.” While we must await an inside account of his campaign for the definitive answer, it seems pretty clear that it was in order to neutralize evangelical opposition that Romney chose to position himself as a party-line social conservative in his race for the Republican presidential nomination. Besides opposing same-sex marriage and abortion as Massachusetts governor, he also—in a state where biomedical research counts as a major industry—turned thumbs down on embryonic stem cell research. This actually put him at odds with his co-religionists in the U.S. House and Senate, all of whom supported it in keeping with the LDS belief that “ensoulment” does not take place until the embryo’s implantation in the womb. Perhaps the most notable moment in Romney’s effort to quiet evangelical concerns came in late October of 2006, when the candidate met with leading evangelical lights, including Jerry Falwell, Franklin Graham, and Richard Land, and assured them that he, like them, accepted Jesus Christ as his Lord and Savior. What seems to concern evangelicals most about Mormons is their claim to be Christians—a claim that evangelicals reject out of hand. In November of 2007, Jonah Goldberg of National Review’s Corner blog, quoted from some of the many responses he received to a post he made on evangelical anti-Mormonism. In the words of one evangelical:

Another comment, along whose lines Goldberg said he received “piles,” ran:

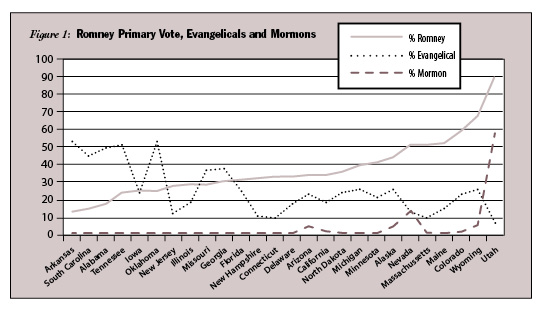

Precisely because of such sentiments, Romney’s strategy of minimizing Mormon distinctives may have been a mistake. Rep. Bob Inglis (R-SC) suggested as much, as did Richard Land of the Southern Baptist Convention when he imaginatively proposed that Mormons hold themselves out as “the Fourth Abrahamic religion.” A more accurate and perhaps even useful idea would be for Mormons to identify their faith as “Judeo-Christian”—inasmuch as their longstanding claim has been to restore ancient Israel as well as early Christianity. Be that as it may, it is worth trying to determine the extent to which Romney’s bid for the Republican nomination was hurt by a lack of evangelical support. Any such determination should take account not only of anti-Mormon sentiment but also of the more widespread accusation that Romney had changed too many of his prior positions for political convenience. For the charge bore some relationship to the sentiment. Had Romney not been concerned about evangelical resistance to his candidacy, he could have avoided the flip-flop charge by, well, not flip-flopping. Making himself out to be less of a social conservative would have made it easier to run on his undisputed strength as a policy wonk, economic sophisticate, and competent manager. Moreover, turning himself into a party-line social conservative may actually have intensified evangelical opposition. Why? Just as people who change positions are deemed untrustworthy because they claim to be something they’re not, so, in evangelical eyes, Mormons claim to be something they’re not; namely, Christians. By shifting to embrace all the “moral values” of evangelicals, Romney may have only reinforced their conviction that Mormons are people who sail under false pretenses. In this regard, it’s important to recall that Romney’s candidacy was supported either directly or indirectly by many evangelical leaders and others on the religious right, including Chuck Colson, Bob Jones III, Richard Land, Tony Perkins, Gary Bauer, Ralph Reed, and Paul Weyrich. Indeed, the candidates’ guide of Focus on the Family Action amounted to a covert endorsement. Tellingly, senior vice president Tom Minnery declared (mistakenly) in an FFA broadcast, “Mitt Romney has acknowledged that Mormonism is not a Christian faith, and I appreciate his acknowledging that.” The widely shared mantra from such pro-Romney leaders in late 2007 and early 2008 was: “We’re electing a president, not a pastor.” Yet the evangelical rank and file withheld the hem of its garment—especially after former Southern Baptist pastor Mike Huckabee emerged as a credible alternative. As Romney advisor Mark DeMoss, who once worked for Jerry Falwell, recalled in a Pew Forum interview last August, “I heard repeatedly from people who said, ‘How can you support a Mormon when we have one of our own running for president? We should support one of our own, a fellow Southern Baptist.’” Huckabee, towards whom religious right leaders were decidedly cool, was not above playing the anti-Mormon card himself. In Zev Chafets’ December 17, 2007 profile in the New York Times Magazine, for example, the former Arkansas governor asked whether it wasn’t true that Mormons believe Jesus and Satan to be siblings. In his campaign literature, Huckabee did not scruple to identify himself as a “Christian leader.” Faced with Huckabee’s growing appeal to the party’s evangelical base, Romney gave the speech on religion that, it seemed, he’d been trying to avoid having to give from the beginning of the campaign. In it, he criticized sectarian religious appeals and played up “moral values” in politics, paralleling evangelical leaders’ line about presidents and pastors. That was on December 6. Less than a month later, Iowans caucused and the primary season was off to the races. A glance at the exit polls makes it clear that evangelicals never warmed to him. The question is whether they doomed his candidacy. A good place to begin to answer it is by discovering how Romney fared in the Republican primaries and caucuses as a whole, and how these results related to the presence of evangelicals. Figure 1 (see below) lists the GOP nominating contests in order of the percentage received by Romney, ranging from a low in Arkansas and to a high in Utah, measured by the solid line.

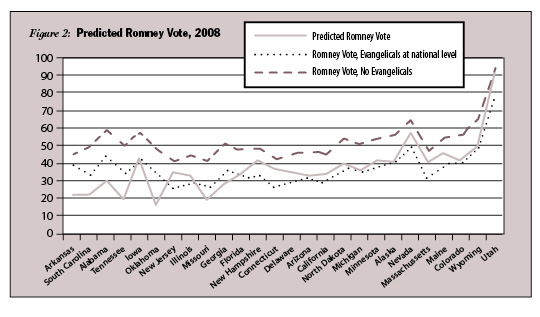

This ordering reflects in part the path of the campaign. Romney started poorly with a loss to Huckabee in the Iowa caucuses and to John McCain in the New Hampshire primary. He recovered with victories in the Michigan primary and in the Nevada and Wyoming caucuses. But this recovery was followed by defeats in the South Carolina and Florida primaries, which set up as a set of disappointments on Super Tuesday, notably in the South. How much did evangelicals have to do with these results? The dotted line in Figure 1 shows white evangelicals as a percentage of adult population in each state. The shape of this line and the Romney vote is suggestive: Overall, Romney did worst in states where the evangelical population was large and best where the evangelical population was small. Across the South, from Florida to Oklahoma, Romney lost; elsewhere, he achieved a number of victories. The Iowa caucuses are an exception to this pattern because evangelicals are not especially numerous in the Hawkeye state. However, Iowa evangelicals have been highly mobilized politically since 1988, when they shook up the Republican nomination contest by sending Pat Robertson to a second-place finish. These aggregate patterns fit the available primary exit poll data. For example, Romney received 11 percent of the white evangelical vote in South Carolina compared to 36 percent in Michigan. Of course, evangelicals were more important in South Carolina, accounting for 55 percent of GOP primary voters as compared to 33 percent in Michigan. In sum, evangelicals tended to oppose Romney everywhere, but the opposition was largest where evangelicals were most numerous, a factor compounded by a large number of evangelicals in the electorate. Of course, evangelicals were not the only cause of Romney’s electoral problems. He faced viable opponents who were also out of favor with some evangelicals, notably McCain; and the winner-take-all rules of most GOP contests turned small margins at the ballot box into big gains in the delegate count. Nor can one assume that the evangelical vote was entirely motivated by anti-Mormon sentiment. For evangelicals to prefer a fellow evangelical like Mike Huckabee need have been no more the result of religious prejudice than it was for Mormons to back their co-religionist, as they did. In fact, the dashed line in Figure 1 showing Mormons as a percentage of the adult population in each state tends to parallel Romney’s success at the polls. Still, these patterns suggest that evangelical opposition made the difference in Romney losses in key contests at critical junctures in the nomination campaign. To probe this possibility more fully, we analyzed the patterns in Figure 1 using a common statistical technique, multiple regression analysis. This technique allows us to determine if the evangelical population of a given state had an independent effect on Romney’s fortunes once other factors are taken into account. Here a simple statistical model of a state’s population worked quite well: The combination of just three measures (the white evangelical and Mormon population, and McCain’s percentage of the vote) predicted 71 percent of the variation in the Romney vote across these states—a strong finding given the crudeness of these measures. McCain was Romney’s principal rival for the nomination overall, and thus the McCain vote is a good control for the competition Romney faced from other Republican candidates. As one might expect, the McCain vote had a negative effect on the Romney vote, all else taken into account. However, the two religion measures each had an independent impact about twice the size of the McCain vote, with the percentage of evangelicals in the state having a negative impact and the percentage of Mormons a positive impact on the Romney vote. Thus the evangelical vote had a negative impact on Romney’s vote totals. But how much of a difference did that vote make in the final result? We can use our simple model to answer the question by making different assumptions about the size of the evangelical population and calculating what the Romney vote would have been under those assumptions, with all else remaining equal. Accordingly, Figure 2 (below) plots three lines. The solid line is the Romney vote predicted by the model based on the actual percentage of evangelicals in each state. The two other lines give a Romney vote under two different assumptions.

The first assumption, embodied in the dotted line in Figure 2, shows what the Romney vote would have been were the evangelical population in each state equal to its proportion of the national population (22 percent). This assumption effectively makes the impact of evangelicals the same in every state. Put another way, it simulates a situation where the evangelical segment of the population constituted a constant in all nomination contests. The second assumption, embodied in the dashed line in Figure 2, shows what the Romney vote would have been assuming that the evangelical population did not exist (set to zero). In effect, this second assumption removes the impact of evangelicals as a voting bloc in every state. It simulates a situation where evangelicals voted the same way as other Republicans. Note that the dotted line in Figure 2 is higher than the solid line in a number of southern states. The difference between the two lines shows that Romney would have won four of the five (only missing in Huckabee’s own state of Arkansas), including the crucial South Carolina primary. Such victories would have substantially improved Romney’s prospects for winning the GOP nomination. But note that he still would have lost the Iowa caucuses to Huckabee and the Florida primary to McCain, while doing less well in a number of states outside the South. This evidence suggests that the variable size of the evangelical population compounded Romney’s problems in key states. The dashed line in Figure 2 is higher than the solid line in all the states. Here the difference between the two lines shows that Romney would have won in the South including Florida, plus Iowa and maybe even McCain’s home state of Arizona as well. In short, under the no-evangelicals assumption, Romney would surely have been the Republican nominee. Thus, it appears that Romney lost the nomination because of his inability to win evangelical votes. Of course, the analysis cannot specify how much of a role anti-Mormon sentiment might have played. All that we can say for sure is that there was abundant evidence of it, and that it helps explain why evangelicals were so loath to vote for Romney. Viewed from this perspective, it seems likely that Romney made a strategic error in aggressively seeking evangelical support by altering his social issue positions. Doing so likely weakened his appeal to Republican voters outside the social conservative fold, and may even have lost him ground among evangelical voters, not only by playing into their anti-Mormon views but also by underscoring the importance of religious criteria in choosing a president. During the Bush years, many rank-and-file evangelicals had heard repeatedly from their leaders about the value of electing a “Christian” president, and according to the teachings of their churches, a Mormon candidate failed to meet the test. It proved difficult for many of these same leaders to argue that evangelicals should support Romney because of his support for “moral values,” especially when there was a viable “Christian” candidate in the race. This turn of events is ironic because the leaders of the religious right have not been especially sectarian in their politics, making common cause with social conservatives from many religious backgrounds—including Mormons. One lesson of the Romney campaign may be that the religious right needs to make a concerted effort to preach a gospel of issues-over-religion to the evangelical rank and file. In fact, there was a good example of this kind of issue-based coalition in the 2008 general election: the passage of California Proposition 8 banning same-sex marriage. Mormons prominently joined evangelicals and Catholics in organizing the pro-Proposition 8 campaign, helping to assemble a broad coalition that included not only white religious voters but also African Americans and Hispanics. If Mitt Romney manages to capture the GOP nomination in 2012, he may have Proposition 8 to thank for it. |