|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links:

Table of Contents |

The GOP's Religion Problem

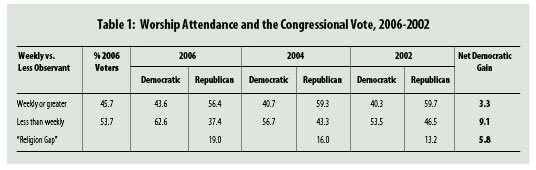

It's finally time to retire that tiresome, inaccurate phrase ‘the God Gap,’ so beloved by pollsters and commentators after the 2004 election,” wrote Amy Sullivan, an editor of Washington Monthly, in the New Republic’s online edition November 8. “Yesterday the God Gap all but disappeared.” On November 11, the Post’s Alan Cooperman reported, “As the results of the midterm elections sank in this week, religious leaders across the ideological spectrum found something they could agree on: The ‘God gap’ in American politics has narrowed substantially.” But in fact, Sullivan and the diverse religious leaders jumped to the wrong conclusion. The full exit poll data released this month show that the partisan divide between more religious voters and less religious ones actually increased in the November election. The religion gap, as we prefer to call it, is not ready for retirement yet. Why the misapprehension? It has to do with the fact that there are two components to the religion gap: the two-party vote of the more religious and the two-party vote of the less religious. Since becoming a subject of general interest a few years ago, the religion gap has most often been represented simply by looking at the more religious—typically defined as those who say they attend worship at least once a week. This made sense because, during the 1990s, it was among these frequent attenders that the gap became most pronounced, in favor of the Republicans. In the 2000, 2002, and 2004 congressional elections, exit polls showed frequent attenders dividing their votes roughly 60 percent to 40 percent for the GOP. Last year, however, only 56.4 percent of them voted for Republican congressional candidates. By that measure, the religion gap did shrink, from nearly 20 percentage points to under 13. But the bigger, overlooked story had to do with the less religious—those who say they attend worship anywhere from a few times a month to not at all. Their support for Democratic congressional candidates grew from 53.5 percent in 2002 to 56.7 in 2004 to a whopping 62.6 percent last year. At 25.2 percentage points, the 2006 difference in the two-party vote among less frequent attenders was larger than the difference among frequent attenders has ever been. The net result of these two vote differentials has been increasing polarization of the electorate along religious lines. This can be seen most clearly if we compare the votes of frequent and less frequent attenders for the same party over the past three elections (see Table 1). What this shows is a religion gap that grew from 13.2 to 16 to 19 percentage points—with most of the growth attributable to the increased preference for Democrats on the part of the less observant.

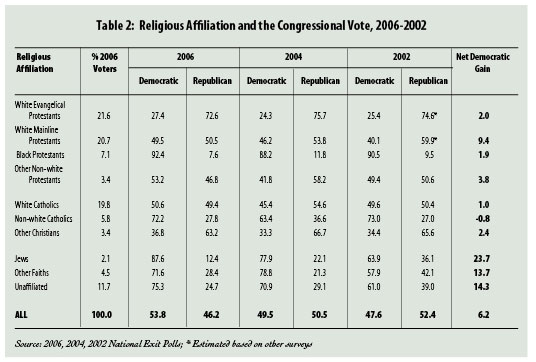

A good index of this trend is the growth in the votes of religiously unaffiliated voters for Democratic congressional candidates from 61 percent in 2002 to 70.9 percent in 2004 to 75.3 percent last year. Overall, the political bottom line for 2006 was that the Republicans had a bigger problem with less religious voters than the Democrats had with more religious ones—a sharp reversal of fortunes from 2004. Of course, religious polarization in contemporary American politics is not all about frequency of worship. Last fall, a large quantity of ink was spilled wondering about whether white evangelicals would jump the Republican ship—or at minimum stay at home—as a result of GOP corruption scandals and, perhaps, a more religion-friendly look on Democratic faces. But, as was widely noted, white evangelicals turned out to vote in large numbers and turned to the Democrats in disproportionately small ones. Overall, 72.6 percent of white evangelicals voted for Republican congressional candidates in 2006—just two percentage points less than in the last midterm election in 2002 and well below the 6.2 percentage-point shift for the electorate as a whole between 2002 and 2006 (see Table 2).

As in 2004, “values” was the issue that counted most for white evangelicals, 44.2 percent of whom ranked it as the issue that “mattered most” in the election, according to a post-election survey by the Pew Research Center. That was more than three times the number of evangelicals who ranked Iraq number one. “Corruption” weighed in at only 5.1 percent. In a word, white evangelicals remained as wedded to the Republican Party as ever in 2006. Together with other conservative Christians (led by the Mormons, who vote Republican in even greater numbers), they represent the GOP’s religious base, constituting about a quarter of the electorate. On the other side of the religious divide are black Protestants, non-white Catholics (Latinos, for the most part), Jews, and those of other non-Christian faiths. In the last election, they voted for Democratic congressional candidates at rates ranging from 92.4 percent (black Protestants) to 71.6 percent (other faiths). The Democratic trend in Jewish voting was particularly striking, going from 63.9 percent in 2002 to 77.9 in 2004 to 87.6 percent in 2006. Together with the religiously unaffiliated, these religious groups, representing nearly one-third of the electorate, constitute the religious base of the Democratic Party. For them, Iraq was the issue that mattered most, far outranking “values.” In the middle in 2006 were white mainline Protestants and white Catholics, each representing one-fifth of the electorate and both closely divided between Democratic and Republican voters. These are swing religious groups par excellence. The white Catholics, trending Republican for a couple of decades, bounced back to the Democrats in 2006. They gave a special priority to the economy, with 32.8 percent naming it the most important issue. Mainline Protestants, once the bedrock of the Republican Party, have grown increasingly Democratic during the George W. Bush presidency. “Corruption” ranked first in the array of issues they considered “extremely important,” according to the exit polls. In the Pew poll, one-third of them said Iraq was the issue that mattered most—nearly four times the number that cited “values.” As we have noted in previous discussions of the religion gap in these pages, there has been an important gender component to the religion gap. Specifically, frequent attending men support Republicans at higher rates than frequent attending women, while less frequent attending women support Democrats at higher rates than less frequent attending men. How did this gender gap fare in 2006? Simply put, it shrank, to 3.5 percent from 7.4 percent in 2002 among frequent attenders and to 5.3 from 6.2 percent among the less frequent. Region is the other dimension of religious voting that we have been tracking, based on the eight regions discussed in the Greenberg Center’s Religion by Region project.[1] In the 2004 elections for Congress, each party carried four regions, with New England, the Middle Atlantic, the Pacific, and the Pacific Northwest going to the Democrats and the Midwest, Mountain West, South, and Southern Crossroads going to Republicans. In 2006, the Democrats carried six regions and, of the remaining two, came within four-tenths of a percentage point of the Republicans in the Mountain West. The outlier was the Southern Crossroads region, which appears to be rapidly turning into the GOP’s regional heartland. In 2002, the Crossroads actually broke slightly in favor of the Democrats in congressional voting, by a margin of 50.2 percent to 49.8 percent. But the Democratic total sank to 42.4 percent in 2004 and to 40.3 percent in 2006, making it the only region in the country where the GOP gained ground last November. The explanation does not clearly derive from the issues profile of the region— although, by a small margin, more respondents cited “values” as extremely important than in any other region. More likely, it lies in some combination of region-wide partisan realignment toward the GOP and residual attachment to President Bush in his native Texas, the region’s largest state by far. What does all this portend for 2008 and beyond? In broad terms, nothing much has changed. Each political party retains the strong support of certain religious constituencies, and across the board, the more religious continue to prefer Republican candidates and the less religious, Democratic. Regionally, the Democrats remain strong in the Northeast and Far West; the Republicans, in the heartland—though increasingly, it seems, parts of the Southeast such as Virginia are in play. It is possible that, as the war in Iraq winds down, the level of Republican voting between both religious segments of the electorate will bounce back to 2002 or 2004 levels, returning control of Congress into GOP hands. It is also possible that Republicans will attract even more support from the most religious voters. But the trend lines suggest otherwise. Just as the growth in Republican voting by the more religious part of the electorate took several election cycles to reach its peak and stayed there for several elections, so it is telling that that the country’s less observant citizens have voted increasingly Democratic in the course of the last few trips to the polls. Meanwhile, the Republican decline among the most religious has been modest, so a simple recovery of these voters is unlikely to offset Democratic gains among the less religious. Throughout President Bush’s first term, annual Gallup surveys found that more Americans believed organized religion should have greater influence in the nation than believed it should have less. For the past three years, however, it’s been the other way around. Democrats, in short, may be able to reap the benefits of resisting the faith-based politics of the other side. Republicans, caught between their solid “values” base and a more secular-minded electorate, may have their work cut out for them. 1The regions are comprised as follows: New England (ME, NH, VT, MA, CT, RI); Middle Atlantic (NY, NJ, PA, DE, MD, DC); South (WV, VA, KY, TN, NC, SC, GA, FL, AL, MS); Midwest (OH, MI, IN, IL, WI, MN, IA, NE, KS, ND, SD); Southern Crossroads (LA, TX, AR, OK, MO); Mountain West (MT, WY, CO, ID, UT, NM, AZ); Pacific (NV, CA, HI); Pacific Northwest (OR, WA, AK). |