|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Table of Contents Spring 2004

Quick Links: From the Editor:

|

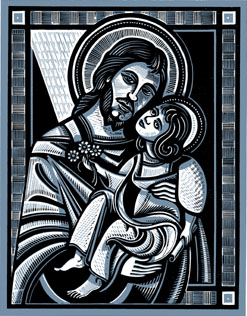

God

the Poppa

On March 18, 2003, Stephen Rubin, president and publisher of Doubleday Broadway, sent 10,000 advance copies of a book by an unknown author to booksellers and the media, hoping to create an instant energy jolt for a publishing industry on the ropes. His author, a former English teacher at a New Hampshire prep school, was Dan Brown; the book, The Da Vinci Code. A month later, Rubin told Bill Goldstein of the New York Times that he was “pleasantly surprised” when the novel debuted at number one on the Times’ bestseller list. One year later, that surprise had escalated into shock and awe. The Da Vinci Code has remained on most bestseller lists, much of the time at number one, and has sold over 5.5 million copies—a feat only bested in 2003 by J. K. Rowland’s keenly anticipated fifth installment of the Harry Potter series. Beyond this purely mercantile bonanza, The Da Vinci Code has invaded popular culture, inspiring cover stories in Time and Newsweek, dominating reading groups, discussion classes at churches and libraries, and picking up a $6 million dollar movie option from Sony Pictures. Is it just, as Sherryl Connelly wrote in New York’s Daily News on March 16, the novel’s uncanny ability to “shock the faithful and entertain everyone else?” Or, as the Catholic Church and evangelical Christians would eventually come to believe, was there a genuinely radical spiritual message to be found somewhere in between the car chases and the puzzles? Initial reviews of The Da Vinci Code spoke with one voice in their praise of what they perceived as a thriller/mystery in the vein of Robert Ludlum or Tom Clancy, that mixed together early Christian history, secret messages in the art of Leonardo Da Vinci, and a Harvard symbology professor (Robert Langdon) caught up in a murder investigation in Paris. On March 17, 2003, Janet Maslin in the New York Times called it a “gleefully erudite suspense novel.” “Are you a paranoid plot-seeker? You’ll love this,” wrote Terry Tazioli a few days later in the Seattle Times. Reviewers saw the novel’s premise—that for 2,000 years the Church conspired to hide Mary Magdalene’s marriage to Jesus—as what Alfred Hitchcock called the “MacGuffin,”—the ultimately irrelevant plot point around which a mystery is spun out. It is clear that these early reviews treated Brown’s bestseller as fiction, pure and simple. Early last summer, The Da Vinci Code still stood firmly atop bestseller lists. Countless newspapers recommended it as the perfect vacation read, from the Hartford Courant (“blends esoteric Catholic lore with contemporary gore”) to the Birmingham News (“a very good mystery”) to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (“a beach book with brains”). Not to say that there were no skeptics willing to speak out. On June 19, Cynthia Grenier of United Press International wrote, “Ban Harry Potter all right, but raise a voice against a book that claims Jesus Christ selected a woman to carry forth his mission on earth? Forget it.” Kathleen Parker’s column in the Orlando Journal Sentinel characterized the novel’s celebration of the goddess as nothing more than “oogedy-boogedy.” And author Stephen King, in his premiere column for Entertainment Weekly August 8, called Dan Brown’s work “drek.” But as the summer passed, reporters began to detect an interesting phenomenon: Women and younger readers were thronging to read a book in a genre (thriller) which is usually geared to middle-aged men. Many were fascinated by Brown’s portrayal of Mary Magdalene as Jesus’ chosen partner, the ultimate example of the “sacred feminine” marginalized throughout church history. For readers not already in the know, The Da Vinci Code revealed that Mary Magdalene was not a prostitute, as decreed by Pope Gregory the Great in 591, but a well-to-do supporter of Jesus. (In 1969 the Vatican publicly came to the same conclusion.) However, it is doubtful that the Vatican would concur with Dan Brown’s other “uncovered truths” about Mary Magdalene. First there was the claim by second and third century non-biblical texts (Gnostic gospels) that Mary Magdalene was Jesus’ favored apostle. Second, the age-old rumor, most recently laid out in the 1982 book Holy Blood, Holy Grail by Michael Baignet, Henry Lincoln, and Richard Leigh, that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were not only married, but produced a daughter. “Mary Magdalene is back,” exclaimed reporter Roxanne Roberts in the July 20 Washington Post. Roberts made clear the connection between casting Mary Magdalene as an apostle equal to Paul and the aspirations of women to take a greater role in their churches. Novelist Margaret George, who wrote Mary, Called Magdalene, told Roberts that Jesus’ companion had now become “the poster girl for womens’ ordination.” By September, book groups, libraries, and church meetings found overflow audiences wanting to know more about the book that kept them up all night. On September 28, the Dallas Morning News described one of many such evenings: Roy Heller, assistant professor at Southern Methodist University, scheduled a biblical analysis of The Da Vinci Code at a local Episcopal church. “They expected that 30 people would show up…More than 500 did.” September also saw some rumbling against the mostly positive media spin that Dan Brown had enjoyed for six months. On September 1, San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker wrote that the idea of Leonardo hiding clues about Mary Magdalene in his paintings was “wiggy.” William Safire, jumping on Brown’s definitions of words from pagan to sub rosa, snickered in his New York Times Magazine column December 28, “The Oxford English Dictionary disagrees.” More significantly, Catholic newspapers suddenly noticed that many Americans regarded The Da Vinci Code as more than just a good read. In Crisis magazine, veteran Catholic reporter Sandra Miesel wrote a lengthy point-by-point attack that accused Brown of producing a “poorly written, atrociously researched mess.” But it was the ABC news special “Jesus, Mary and da Vinci,” a one-hour “sweeps week” investigation of the novel’s theories that aired November 3, which provoked the major media backlash. With Elizabeth Vargas as on-air reporter, the special was anything but hard news, relying heavily on evocative music and vague statements like “What if we told you” and “I guess we’ll never really know.” Interestingly, two of the experts interviewed were scholars whose new books would ride the crest of The Da Vinci Code to become bestsellers: Elaine Pagels (Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas), and Karen King (The Gospel of Mary of Magdala; Jesus and the First Woman Apostle). While both credited The Code with exploring the role of women in early Christianity, neither bought the premise of a married Jesus. If, up to then, attacks on The Da Vinci Code had been muted, the response to ABC’s “investigative report” was visceral. Even before it aired, Ray Flynn, president of the policy group Your Catholic Voice and former mayor of Boston, told the Boston Globe the upcoming special represented “an all-time low in offending Christians.” The conservative Catholic order Opus Dei was understandably put out at being cast as the book’s evil empire (complete with a murderous albino monk with a taste for self-flagellation). A fact sheet posted on its website (www.opusdei.org) reassured readers that the book’s “bizarre depiction of Opus Dei is inaccurate.” While calling the monk’s behavior “exaggerated,” the site explained, “Those who seek to advance in Christian perfection must mortify themselves more than ordinary believers are required to do.” Journalists, in particular religion writers, took note. A few examples of articles challenging The Da Vinci Code in the wake of the ABC special were The Washington Times (“Married Jesus Breaks the Code”), the Associated Press (“Was Jesus Married? A Novel and ABC News Erase the Line Between Fiction and Fact”), and The Christian Science Monitor (“Who Was Mary Magdalene? The Buzz Goes Mainstream”). While Monitor staff writer Jane Lampman’s piece dismissed the Jesus/Mary ménage, it offered another explanation for the novel’s incredible success. Ben Witherington III, professor at Asbury Theological Seminary told Lampman, “America is a Jesus-haunted culture, but at the same time it is biblically illiterate. When you have that odd combination, almost anything can pass for knowledge of the historical Jesus.” A smaller number of journalists and clergy wondered if it was fair to hold what was, after all, a novel, to the rigors of historical truth. Steve Maynard of the Tacoma News Tribune reported on January 2, for example, that the Rev. David Norland, associate pastor at Emmanuel Lutheran Church in Tacoma, was comfortable making the distinction between “a good piece of fiction” and “bad, bad theology.” Part of the responsibility for the confusion must land at the door of Dan Brown, who told Linda Wertheimer on NPR’s Weekend Edition April 26, “The only thing fictional is the characters and the action that takes place. All of the locations, the paintings, the ancient history, the secret documents, the rituals, all of this is factual.” Wertheimer let that drop unchallenged. In spite—or because—of the growing controversy, Newsweek ran a cover package December 8 in which religion writer Kenneth L. Woodward worried that “the danger is that feminist ideology will overreach the text.” A sidebar, “Decoding The Da Vinci Code,” validated some of the book’s theories and dashed others. An associated feature, “The Bible’s Lost Stories,” gave credit to Brown for popularizing the trend among scholars to research overlooked women in the Bible, from Mary Magdalene to the Old Testament figure Judith, who saved Jerusalem by beheading an enemy general. Newsweek emphasized that many biblical scholars and feminists did not find The Da Vinci Code’s tale of a romantic relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdalene to be convincing—or necessary. “Let’s not continue the relentless denigration of Mary Magdalene by reducing her only importance to a sexual connection with Jesus,” declared John Dominic Crossan, professor emeritus of religious studies at DePaul University in Chicago. “She’s not important because she was Mrs. Jesus.” For their part, evangelical Christians woke up to the debate after the turn of the year, with Christianity Today establishing an anti-Da Vinci Code section on their website (www.christianitytoday.com). On February 16, Darrell Bock, professor at the Dallas Theology Seminary, told Julia Dunn of the Washington Times that the book “is an attempt to reshape our culture and our Christian beliefs.” Bock’s own “counterpunch” can be found in his book, Breaking The Da Vinci Code: Answers to the Questions Everybody’s Asking, which was released in April. As The Da Vinci Code wrapped up 12 months (and counting) at the top of the bestseller lists, a new question popped up in the media: What had made it so successful? Explanations fell into different camps. Elizabeth A. Johnson, a Fordham University professor, was one of many who found the reason in a widespread distrust of the Catholic hierarchy: “In light of the sex abuse scandal, most in the Catholic Church would not put it past the Vatican to suppress [controversial issues],” she told the Los Angeles Daily News on February 1. Others saw the book’s success as evidence that prejudice against Catholicism is still alive and well. Writing in The New Republic March 2, Jennifer C. Braceras claimed, “Brown’s portrayal of Catholic teachings and the Church as an institution reinforce the perverse stereotype of Catholicism as a bizarre cult.” The majority of articles, however, put the novel’s phenomenal impact down to its re-imagining of Jesus as a husband and father, and Mary Magdalene as a spiritual leader. Novelist Sue Monk Kidd, whose bestseller The Secret Life of Bees paid tribute to the black Madonna, was asked by Amy Wilson in the Orange County Register why the reclaiming of female spiritual figures had such a wide appeal. “Because what we do not value in God,” she answered, “we do not value in our culture.”•

|