|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links:

From the Editor: |

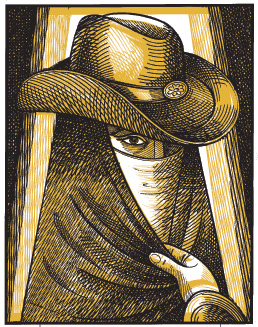

Sharia

Isn’t OK

In November, Oklahoma’s voters overwhelmingly supported an amendment to the state constitution that would ban state courts from applying sharia, the religious law of Islam. That vote draws on old tropes in American religious and political history, which are themselves more interesting than the law and the resulting lawsuit challenging its compatibility with the U.S. Constitution. The amendment’s sponsors conceded that there is no imminent threat of sharia taking over America’s courts—a point made in a pre-election story by Nicholas Riccardi in the Los Angeles Times on October 29 headlined, “Oklahoma may ban Islamic law: Backers say it isn’t a problem now, but why wait?” Muslims called the bid a scare tactic. The Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment preclude states from imposing religious law on their citizens. An Oklahoma court cannot tell Catholics or Jewish citizens seeking a divorce that their case will be decided under canon law or halakha (Jewish law). Neither can it require that parties involuntarily refer their cases to religious tribunals. Moreover, federal constitutional law even prohibits courts from interpreting religious law, as they are sometimes asked to do when a doctrinal split emerges between a local church and a national body. Silliness, however, does not make a law unconstitutional. Singling out one faith for regulation does. Entirely unsurprisingly, a federal district court quickly issued a preliminary injunction against enforcement of the provision on the ground that it violates the most fundamental assumption of the U.S. Constitution’s religion clauses—that government must treat all similarly situated faiths identically. Since both Catholicism and (Orthodox) Judaism, to name but two, also have bodies of religious law, but are not barred from recognition by Oklahoma’s courts, the unconstitutionality of the provision is plain. Oklahoma has nonetheless appealed. Precisely because all institutions of government are forbidden to impose religious law on non-consenting citizens—and hence the amendment was in large measure unnecessary—it is a fair question whether plaintiffs in the challenge can show they are hurt by it. There are uncommon but possible applications, such as voluntary arbitration of a dispute under sharia law, a religious freedom claim based on that law, or an agreement made pursuant to the law of a nation applying sharia law. The ban can in any event be easily circumvented. For example, instead of drafting a will that states that property should be distributed according to sharia, the drafter can simply follow those rules in apportioning his or her estate. The point about legal irrelevancy was made, paradoxically, by the proposition’s legislative sponsor (a Republican), who criticized the outgoing (Democratic) Attorney General for not forcefully raising an objection to the plaintiffs’ standing to maintain the lawsuit on the ground that the adopted language accomplished nothing. Perhaps the charge is best understood as an indication of the partisan nature of the anti-sharia effort, and it’s probably not entirely an accident that the charge was carried in a November 8 story on Fox News by Ed Barnes. Of course, the real harm the amendment works is conveying an unmistakable message that Muslims who observe sharia are not welcome in Oklahoma. Not a single article about the amendment cites any law professor as holding the view that the provision is constitutional, though several University of Oklahoma law professors are quoted as declaring the bill plainly unconstitutional. This is not a reflection of bias by the reporters. I am unaware of any law professor who thinks the provision defensible on the merits, though there are professors who think the pending lawsuit is premature or that the plaintiffs lack standing to sue. In the late 19th century, evangelical Christians, in the face of rising Catholic political strength, raised the specter of a Catholic takeover. The 19th-century Catholic Church, by way of such papal encyclicals as the 1864 Syllabus of Errors of Modernism, campaigned against many of the most fundamental principles of American political life, notably the separation of church and state. Protestants, led by President Grant and many of the leading Protestant clergy of the day, responded by pushing for state constitutional amendments (so-called Blaine Amendments, after the leading proponent of such efforts) banning all state financial aid to religious institutions. These efforts were in part sincere, and in part a wedge issue to encourage Protestants to rally to the Republican Party to counter rising Irish (read: Catholic) influence on the Democratic Party (the Party, it was famously said, of Rum, Romanism and Rebellion). While neutral in form, these amendments were plainly aimed at the Catholic Church, which was then vigorously campaigning for aid for its parochial schools. The parallels between the campaign to enact the Blaine Amendments and the anti-sharia law effort are striking. First, each arose in the context of political jockeying, and each was used to arouse proponents’ political base against forces described as “alien” and “un-American.” In the case of the anti-sharia amendment, these efforts were apparently successful. The Republican surge in Oklahoma (they captured all branches of state government) has been attributed to the sharia proposition on the ballot and a late telephone campaign on its behalf by an organization committed to it. Though several news stories and op-eds emphasized this point—one story, by James C. McKinley, Jr. in the New York Times on November 14 even quoted an Oklahoma Democratic legislator who had voted against placing the sharia law proposition on the ballot and as a result faced charges of being a supporter of extremist Islam in the election—the evidence for the proposition is thinner than one would expect. No hard evidence showing that the issue pushed people to the polls was cited, nor are there numbers pointing to an increase in voter turnout (as compared to, say, the prior midterm elections). Riccardi’s Los Angeles Times story did cite poll data indicating that support for the proposition soared: from 49 percent in favor, 24 percent against, and 24 percent undecided in July to an endorsement by over 70 percent of voters at the November polls. Several stories did note that Newt Gingrich—who is testing the waters for a 2012 presidential bid—supported the anti-sharia amendments. So did Sarah Palin, though less vociferously. This suggested to Marc Ambinder, writing in the October Atlantic, that sharia could be a wedge issue with mileage. Second, as was the case with Blaine Amendments, the targets of the amendments were portrayed as alien and “un-American,” undermining core American values, or, most tellingly, America’s Christian or Judeo-Christian heritage. (In the case of Blaine, it had been America’s Christian heritage only that was at stake, Catholics not being considered good Christians.) The idea was expressed in regard to Oklahoma most eloquently by that well-spoken xenophobe, Pat Buchanan, in a syndicated column published in the Niagara Falls Reporter (among other places) November 20: “The Amendment should be seen as ‘a cry from the heart of America’ that we are and wish to remain a Western nation, a predominantly Christian country and we wish to be ruled by our Constitution.” Just how seriously the Judeo-Christian point is taken is reflected in the pledge of the American Center for Law and Justice—which typically opposes laws restricting private parties’ ability to follow their religious beliefs—to help defend the law and to draft similar, “more constitutional” legislation for enactment in other states. Texas, Wyoming, and Arizona are now considering such proposals, and, as Donna Leinward reported in a comprehensive story in USA Today on December 9, other states as well. Third, the targets of these proposals react with protestations of their commitment to accepting American norms, though in both 19th- and 21st-century cases the targeted group displayed splits over how to Americanize. Fourth, as Omar Sacirbey wrote on December 9 for the Religion News Service, much of the support for the anti-sharia effort comes out of the evangelical movement, with the American Center for Law and Justice taking a prominent role. The director of Oral Roberts University’s Center on Israel and Middle East Studies likewise supported the effort, according to a Huffington Post blog by Christopher Brauchli on November 5. It is important to recognize, however, that other evangelical groups and recognized evangelical clergy do not appear to be part of this effort. Fifth, though the point is not often made, neither 19th-century opponents of Catholicism nor contemporary opponents of sharia law are conjuring up a wholly non-existent threat. The Syllabus of Errors directly targeted key Western political ideas central to American constitutional thought. Only the willfully blind could deny that both around the world and in small pockets of America, there are some Muslims intent on imposing sharia law at least on all Muslims, if not on society generally. In the context of modern America, the threat of this actually happening is infinitesimally small, and in any event (as several writers note), does not justify the discriminatory singling out of Islam in Oklahoma’s constitution. But neither do the shortcomings in the amendment justify ignoring the stake all Westerners have in the battle against these extremist efforts. There are, however, important differences between Blaine and anti-sharia law amendments. As nearly all of the news stories and many of the critics of Oklahoma’s amendment were quick to observe, there is almost no evidence that sharia law is about to break out into American law. There was a much-discussed New Jersey case involving a trial judge’s refusal to issue an order of protection (and not, as several stories suggested, aborting a criminal prosecution) to the wife of a Muslim couple subject to sexual and physical assaults because the husband, in alleged reliance on his Pakistani (Islamic) cultural background, did not believe his actions wrong. The refusal to issue an order of protection was quickly and decisively overturned by an appellate court as opponents (but not proponents) are quick to note. By contrast, mid-19th-century Catholics vigorously insisted on their right to equal funding of Catholic schools, and they had substantial political clout. Popes did indeed insist that separation of church and state was a heretical idea. Popes are not marginal actors. Even more importantly, although the target of the Blaine Amendments was undoubtedly the Catholic Church, the adopted amendments were neutral in form and therefore applicable to all faiths. No doubt, in the 19th century the primary purpose of the Blaine Amendments was to target Catholic schools and, to a lesser extent, Catholic social services agencies. In the fullness of time, however, the neutral cast of the prohibitions has restrained government aid to a wide range of faiths. The anti-sharia provisions, by contrast, can never be applied other than to Islamic law. As widely observed, many other faith groups, including Orthodox Jews and evangelical Christians, maintain their own systems of adjudication—not only for primarily intra-faith disputes (say over ministerial fidelity to dogma) but to the full range of human endeavors, including business and marital disputes. These would, of course, be unaffected by Oklahoma’s amended constitution. Pepperdine University Law Professor Michael Helfand pointed out in an especially clear exposition published as a November 10 op-ed in the Los Angeles Times that courts routinely enforce agreements to religious arbitrations of this sort, provided they are the product of the voluntary decision of the parties. As of this writing, the Texas Supreme Court is considering the enforceability of a commercial agreement calling for arbitration of disputes pursuant to sharia or Saudi law. Helfand underscores that courts also police the results of such arbitration awards for violations of fundamental public policies. Several stories, including one by Gina Miller in the November 9 Dakota Voice, made the point that such arbitrations have been for some time allowed without evident harm in Great Britain. (A law review article by Washington and Lee Law Professor Robin Fretwell Wilson, which appeared during the 2010 election cycle, reaches a more ominous conclusion about the situation in the U.K.) Allowing such arbitration awards is, on the one hand, a reflection of the liberal principle that people should be able to govern their affairs as they choose, including by abiding by religious principles. On the other, the liberal state is defined by the uniform rule of secular law binding on all citizens equally. Had Oklahoma chosen to bar all arbitration, or all arbitration applying non-Oklahoma law—as Ontario did a few years ago in regard to family law in order to forestall Islamic law arbitrations thought unfair to women—a different issue would be presented. Oklahoma, though, chose to target one faith among many. The most salient difference between 19th-century anti-Catholicism and contemporary anti-sharia efforts, though, is this: The anti-Catholic crusade was endorsed by much of the national elite, beginning with the President of the United States and much of the Protestant establishment. By contrast, the 21st-century elite for the most part treated the Oklahoma effort with undisguised contempt. That was particularly true in the media. Consider this roster: Clarence Page in his syndicated column of November 16, 2010; Roger Cohen in the December 6 New York Times; Garrett Epps and Marc Ambinder, in the November Atlantic; Eugene Robinson in the September 21 Washington Post; and editorials in the November 28 New York Times, the November 11 Los Angeles Times, and the October 31 Newark Star Ledger, as well as in several Oklahoma papers, including the November 10 Oklahoman. All were scathing in their criticism of the proposed amendment. In a biting column in the November 16 Washington Post, Michael Gerson, President George W. Bush’s former speechwriter, made the important point that the adoption of the proposition would hurt America’s efforts to improve relations with the Islamic world. Yet as powerful and cogent as the opposition voices were, they failed to persuade almost three-quarters of the Oklahoma electorate. The point is not that voters can be misled by cynical, power-hungry demagogues, though that is certainly true. It is that there is a yawning gap between the intellectual elite, liberal and conservative, comfortable with a recognition that in the 21st century Americans must become accustomed to living in a multicultural, multi-sectarian world, and those Americans who, though prepared to tolerate much, are insistent on retaining an older vision of America. Mocking those views as, for example, Cohen, Gerson and Coleman did, or as the Star Ledger did in headlining its editorial “Oklahoma Goes Rogue with Nutty Ballot Issue,” only confirms the suspicions of many Americans that the elite doesn’t understand them, and doesn’t much care for the United States they yearn for. That sort of dismissal will only backfire. |