|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links:

From the Editor: |

The Religion Gap Abides

These patterns, however, should not be taken to mean that religion ceased to matter at the ballot box. In 2010, what we call the “religion gap” (or more popularly, the “God Gap”)—the preference of weekly worship attenders for Republicans and of less frequent attenders for Democrats—yawned as wide as ever. The exit polls showed that Republican congressional candidates received the votes of 59 percent of the frequent worshipers but just 44 percent of the less observant. On the flip side, the Democrats got 56 percent from the less frequent attenders and just 41 percent from the weeklies. In both cases, the gap was 15 percentage points—nearly twice as big as the election’s gender gap. (The GOP won 57 percent of men’s votes, 49 percent of women’s.) So even though social issues were foremost in few minds, this simple measure of religiosity, worship attendance, had a powerful impact on the vote. And this impact holds even when the impact of other demographic variables is taken into account, including gender, income, age—and, indeed, religious affiliation. What’s notable is the constancy of the pattern. Over the past decade, the gap in the vote has changed very little in national elections, whether presidential or congressional contests.

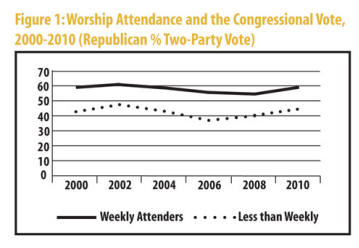

Figure 1 plots the Republican percentage of the two-party congressional vote for respondents who reported attending worship weekly or more often and those who reported attending less frequently (including not at all). The vertical lines show the size of the religion gap in each election. Although the size of the Republican vote varied—dropping in 2006 and 2008, when the Democrats gained control first of Congress and then of the presidency—the gap itself changed very little. In 2006, it was actually larger (19 percentage points) than it was in 2000 and 2008 (15 points). In 2010, it was identical (15 points).

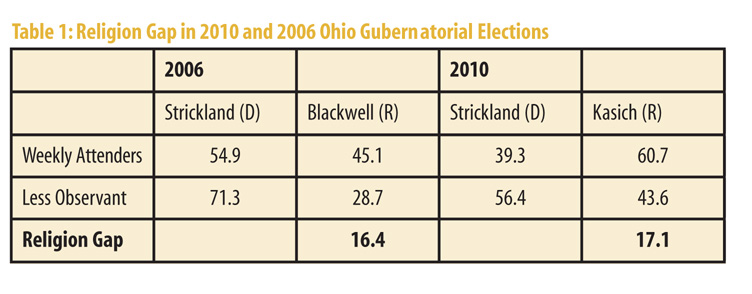

Figure 2 plots analogous data from the exit polls for the Republican percentage of the two-party presidential vote in 2000, 2004, and 2008. Although the vote total varied from election to election, the size of the gap stayed the same, at 17 points. The religion gap persists by gender, income level, and religious affiliation. For example, while white evangelical Protestants vote Republican more than white Catholics, within each group there is a pronounced difference in partisan preference based on worship attendance. Indeed, statistical analysis shows that worship attendance is one of the most powerful demographic predictors of American voting, typically exceeded only by race. And since African Americans tend to be frequent worship attenders who vote strongly for Democratic candidates up and down the ticket, taking race into account only enhances the importance of the gap among white voters. The religion gap appears in state elections as well, varying a bit from place to place. We can see more clearly how it functions by comparing its impact in the 2006 and 2010 gubernatorial votes in the swing state of Ohio. These elections had notably different results but, as Table 1 shows, the religion gap remained strikingly constant.

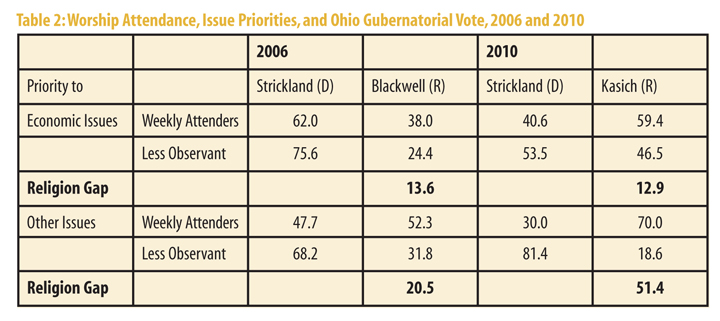

In 2006, Democrat Ted Strickland ran a religion-friendly campaign against Republican Ken Blackwell, a staunch conservative who as secretary of state had alienated even members of his own party by his aggressive partisanship and strong opposition to abortion rights. Strickland won in a landslide, 62 percent to 38 per cent, picking up 54.9 percent of the weekly attenders as well as 71.3 percent of the less observant. The religion gap was 16.4 percent. Strickland showed that, under the right circumstances, Democratic candidates could do well among religious voters. But even so, his Republican opponent did markedly better with weekly attenders than among the less observant. Running for re-election in 2010, Strickland was narrowly defeated by former Republican congressman John Kasich, 49 percent to 51 percent. Yet as different as the result was, the religion gap—17.1 percentage points—remained almost the same as it had been four years earlier. With the economy taking priority, Kasich won 60.7 percent of weekly worship attenders while Strickland took 56.4 percent of the less observant. Consider Table 2, which looks at only those Ohio voters who ranked economic issues as number one in importance. In 2006, when this group comprised a little less than half the voting public, the Democratic candidate won majorities of both frequent and less frequent attenders, but did significantly better among the latter: The religion gap was 13.6 percent.

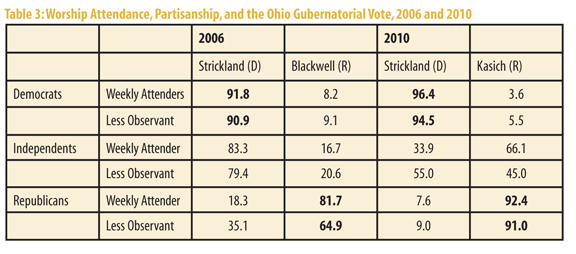

In 2010, almost nine out of 10 Ohioans fell into this group, and Kasich won a slight majority. Of the frequent attenders, he took 59.4 percent, while Strickland picked up 53.5 percent of the less observant. And despite the shifts, at 12.9 points the religion gap was close to what it had been in 2006. The point to bear in mind is that in both elections, “economic” voters divided strikingly according to religiosity. But if the religion gap cuts across demographic lines and is not driven by issue preferences, what explains its impact on the vote? The answer is that, to a significant degree, religious observance has itself become a determinant of political partisanship. Table 3 looks at the religion gap for Democrats, Republicans, and Independents, in the 2006 and 2010 Ohio gubernatorial elections. It is hardly surprising that self-identified Democrats should vote heavily for the Democratic candidate and self-identified Republicans for the Republican. In 2006, a significant number of Ohio Republicans chose to go the other way, but differentially according to level of observance: less than one out of five frequent worship attenders as opposed to more than one out of three of the less frequent.

In 2010, the voting patterns of self-identified partisans reverted to normal—over 90 percent—and the 2006 religion gap of over 16 points that had opened up on the GOP side all but disappeared. Meanwhile, on the Democratic side, the minor religion gap in both elections showed weekly attenders to be slightly more likely to vote for Strickland—a reflection of the Democratic loyalty of black voters, who tend to be regular worship attenders. Indeed, in 2010, Strickland won 93 percent of the black weekly attenders but only 88 percent of less observant African Americans. That year, the black vote constituted 20 percent of Strickland’s total. Now consider the independents. In 2006, their vote shows a small religion gap in reverse, with Strickland doing slightly better among the weekly attenders (a rare occurrence). But in 2010 the independents split, with frequent attenders going strongly for the Republican while the less observant stuck with the Democrat, but at a much lower rate than four years earlier. Looked at from this perspective, the Republican won in 2010 because he was able to reestablish the religion gap among independents. Kasich won the independent vote over all by capturing disproportionately those independents most likely to vote Republican—the frequent worship attenders. What Table 3 shows is how deeply embedded religion has become in contemporary party coalitions. In any given election, circumstances can shift the religion vote one way or another at the margins. But frequent attending Republicans are the hardest votes for the GOP to lose and the easiest to recover. The remarkable stability of the religion gap over the course of a series of quite different elections suggests that reports of the gap’s demise, which occurred periodically during the last decade, will be premature for quite some time. Indications are that once the votes are counted and the exit polls tabulated in November 2012, it will prove to be as robust as ever. |