|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Link:

Introduction: The Congruence Between the Scientific and the Secular Science Education and Religion: Holding the Center The Competition of Secularism and Religion in a Science Education Scientific Literacy in a Postmodern World High School Students Speak Out

|

A Special Supplement to Religion in the News:

The Congruence Between the Scientific and the Secular

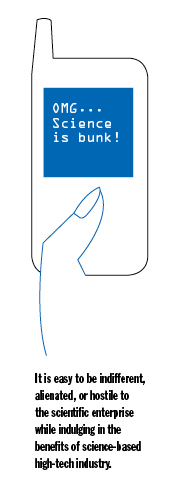

Embedded in a certain concept of modernity is the idea that science is a major building block of the secular worldview and that the progress of science is, de facto, the triumph of the secular worldview. This outlook arises from the close historical, philosophical, and intellectual relationship between the natural sciences and secular ideas and values. There are indeed many points of congruence between the scientific and the secular, including commitments to reason, skepticism, systematic knowledge, empiricism, and the procedural aspects of scientific methodology—all of which form the basis of a common commitment to the impartial generation of truth. The methodical use of empirical data in scientific research accords with the “worldly” focus of secular ideas and values. The scientific and the secular appeal to the experience of ordinary people under relatively common, and replicable, circumstances. Modern science is thus properly considered an agent of secularization because of its association with free inquiry and freedom of thought and expression. It also qualifies by virtue of its role in undermining the superstition, ignorance, and belief in magic that so often fostered fear and authoritarianism in human societies. The Scientific Revolution of the 17th century involved an unprecedented endeavor to secure the autonomy of the scientific enterprise from religious authority. It established core methodologies that investigators use when they experiment, when they confirm what others have done, when they follow through on the processes of not only generating but testing, confirming, and denying knowledge of one sort or another. This cultivation of a naturalistic worldview and a skeptical spirit encouraged believers and non-believers alike to cultivate a new mental habit of demanding good, empirically verifiable reasons for their beliefs and to reexamine the factual basis of moral causes. It was the proponents of Copernicus’ theory of a heliocentric universe who began using the phrase libertas philosophandi (freedom of philosophizing—free inquiry) which eventually found its way into the full title of Spinoza’s famous Theological-Political Treatise of 1670. Galileo pronounced the fundamental scientific principle that “Two truths cannot contradict each other.” In 1660, when the famous Royal Society of London was founded, its members asserted that science was based on the principle of testing ideas by experiment, adopting as their motto “Nullius in verba,” which loosely translated means, “Take nobody’s word for granted.” They also went on to commit themselves to exclude matters of religion and politics from scientific discussions. The sciences, in terms of their ethos and organization, can also be viewed as the best example of the triumph of the essentially secular ideas embodied in the French Revolution’s slogan of Liberté, egalité, fraternité and its promise of la carrière ouverte aux talents—meritocracy. With its universality, objectivity, and commitment to meritocratic peer review, science seems to admit of egalitarianism and real democracy more than any other area of human enterprise. Its ethos leads to a universalism of good ideas and empirical data that are accepted from whatever quarter they emerge. Science has an anti-authoritarian tradition based on the concept of self-generated human progress—constantly reforming and refining itself from within without external guidance. In the words of the sociologist Max Weber, science is a secular “vocation” and “scientific work is chained to the course of progress…; every scientific ‘fulfillment’ raises new ‘questions’; it asks to be ‘surpassed’ and outdated.” Today, scientific education and research are commonly viewed as pillars of secular lifestyles and social organizations that, as a matter of principle, reject the authority of any particular religious association or doctrine. Along the lines of Isaiah Berlin’s celebrated distinction between “negative” and “positive” conceptions of freedom, science and secularism can thus be seen as congruent because of their common endeavor to demarcate areas of human action that are “free from” external, particularly religious, authority. The interplay of science education and secular values has public policy importance in a number of areas—particularly with respect to economic prosperity and geopolitical strength. In the United States, the dream of harnessing scientific progress to the betterment of all citizens arose during the Progressive era in the early 20th century—the heyday of belief in the public school and the birth of the research university. The Progressive idea of universal education and progress, exemplified in the writings of John Dewey, was predicated on the notion that the form of education that can truly empower individuals is scientific in spirit and principle. It was originally propagated by a coalition of industrialists, public servants, and academicians who believed that science and its universal method of knowledge acquisition could unify the nation and generate economic and social progress. This vision assumed that science was and should be value-neutral and indifferent to the varied identities and beliefs of an increasingly diverse American nation. The Progressives professed that the “indifference” of science—its disinterested search for truth—was basic to its credibility and strength. Yet in our time this ideology, which conceives of science as a common good embodying value-neutral knowledge, has come to be disputed by certain communities that feel threatened by the implications of scientific research for their own worldviews. In the academy, a fashionable relativist and postcolonial outlook belittles the achievements of science and instead valorizes “local knowledge” grounded in indigenous or ancient conceptual categories. More importantly, science has come under challenge from a resurgent religious fundamentalism, which above all seeks to protect young people from being taught scientific ideas that seem to threaten religious beliefs. Paradoxically, the very triumph of science has enhanced its vulnerability to these forms of “skepticism.” As it has advanced and grown, science has become more complex and harder for ordinary people to comprehend. In an age when technology is increasingly user-friendly, it is easy to be indifferent, alienated, or hostile to the scientific enterprise while indulging in the benefits of science-based high-tech industry. The widening gap between the scientific community, as a perceived elite, and much of the general public has gradually eroded the status of science as a common good. Even though most Americans still claim to value science highly and believe it will continue to make their lives better, too many steer clear of it in school. As a result, the traditional model of science education now appears more elusive than ever before. Although parents recognize that their children’s future depends on a good education, the swell of scientific illiteracy prevents them from assessing with confidence and clarity what actually constitutes a good education. It is not too much to say that the dream of science for all has become an empty cliché rather than a source of personal inspiration. The result is a mood of ambivalence and confusion among many science educators. In order to better understand what the educational system is up against, the ISSSC undertook two initiatives in the summer of 2006. One was an academic workshop on “science education and secular values” featuring papers by leading experts in the area of science education and scientific literacy. Abridged versions of three of these papers are included in this supplement. In addition, the ISSSC sponsored an essay contest for Connecticut high school students. Its rather revolutionary aim was to learn something of what was happening on the ground by directly asking the rising, techno-savvy generation of young people to explain the unpopularity of science among their peers. A short report on what they had to say follows. Needless to say, science as a model of human growth and development neither can nor should be immune from scrutiny and debate. Questions inevitably arise. What is the nature of authority in science? Do problems in science classrooms reflect broader problems concerning the public understanding of science? What level of science literacy is necessary or desirable for the ordinary citizen? Should our concern be on the inputs (what is taught to students) or on the outputs (what is learned)? Can the teaching of science in institutions of public education be predicated on the assumption that it benefits every student, regardless of his or her cultural identity or personal aspirations? How can the claim to know what benefits other persons, which is either implied or explicitly professed in contemporary treatises on science education, be squared with the ideal of freedom of choice? It is only appropriate that our authors do not all agree on the answers. |