|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Table of Contents Spring 2005

Quick Links:

From the Editor: What Athens Has To Do With Jerusalem Evangelicals Discover the Culture of Life The Faith-Based Initiative Re-ups

|

What Athens

Has To Do With Jerusalem

The cassock does not make the priest” is an old Greek proverb that has been confirmed in spades during a year marked by a gaudy explosion of scandal in the Greek Orthodox Church. “Holygate,” as some Athens journalists have called it, has rocked the church in Greece as well as the Holy Land, where Orthodox Christianity has had a strong presence for at least 1,500 years. Since February, the head-lines in Greece have been dominated by reports of shady secret land deals, the system-atic bribery of judges, poly-morphous sexual misconduct, drug -dealing, and an almost infinite variety of embezzlements by very senior bishops and priests. Indeed, one Greek commentator estimated on May 26 that about half of the Greek state church’s 86 diocesan bishops stand accused of crimes or breaches of ecclesiastical discipline of one degree or another. The scandals caused the dismissal of the Patriarch of Jerusalem and may yet claim the Archbishop of Athens. They have certainly damaged the standing of what had been Europe’s most entrenched and privileged state church. “The Greek public can only watch dumbfounded as the country’s bishops humiliate themselves on television, tossing barbs at each other and trading accusations of forgery, blackmail, dissolute living, even drug trafficking,” Kathimerini (The Daily), the conservative Athens daily that is Greece’s closest approach to a newspaper of record, editorialized on February 1. About 95 percent of Greeks are baptized Orthodox Christians and, hitherto, few Greeks thought it possible or desirable to disentangle the twin strands of Hellenism and Orthodoxy. “Not even the most passionate anti-clerical type could have imagined what our eyes are seeing and our ears are hearing, Thanassis Georgopoulous, a columnist for Ta Nea (The News), a mass-market, leftist newspaper in Athens, wrote during the early stages of the crisis. “Not even the most fanatical enemy of the church could have planned such a deep and painful crisis.” The Greek scandal broke late in January, when an Athens radio station broadcast tapes of alleged telephone conversations in which Metropolitan Panteleimon of Attica, a large diocese covering much of suburban Athens, boasted that he had the power to influence judicial decisions in court cases involving the church and in criminal matters. Other tapes were soon broadcast in which Panteleimon made “love talk” to young men. Further investigation produced charges that the metropolitan also controlled a relative’s 4 million Euro bank account, which he administered as a mutual fund, and he was soon accused of skimming the receipts of collection boxes in several monasteries in Attica. At about the same moment, Greek prosecutors arrested a priest named Iakovos Yiosakis and charged him with operating an in-fluence peddling ring that may have bribed up to 30 Greek judges to obtain favorable rulings in matters ranging from civil lawsuits to criminal charges against drug dealers. Yiosakis, who had also been involved in the 1990s in a scandal over homosexuality at a monastery on the island Kythera, was soon charged with illegally exporting historic icons, and charged in the United States with embezzling money from a small Greek Orthodox parish in Chicago where he had taken a pastor position in the middle 1990s. Newspapers then carried reports that Metropolitan Theokletos of Thessaly had been arrested the previous year during a police drug raid on a gay bar in Central Greece. Theokletos had been dressed in civilian clothes and was accompanied by a high official of the national church’s central administration. Theokletos, who was also charged by rivals with dealing drugs and running a male brothel, happened to be a protégé of Archbishop Christodoulos of Athens, a charismatic, fire-breathing Greek patriot and, until this point, an extremely popular figure in the country. In February, an explosion of charges and revelations followed. One tabloid published an alleged photo of a nude, 91-year-old bishop in bed with a young woman. Compromising photos of other high church leaders followed, as did a blizzard of financial charges. The bishop of the southern city of Corinth was accused of embezzling hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of parish funds, and the bishop of the island of Chios was charged with maintaining an unexplained $17 million bank account in the United States. On the island of Patmos, prosecutors were investigating reports that a former abbot of the Monastery of St. John the Divine had sold monastery land to his brothers for a fraction of its value. “Hour by hour, information and evidence mounts to confirm the relationship of Archbishop Christodoulos with the underworld,” the newspaper Hora (The Hour) editorialized on February 25. “He does not seem to understand that he is sinking in lies.” Christodoulos had to endure a long series of humiliating interviews on television in which he had to drop his first line of defense: that the church was under attack by enemies of Orthodoxy and Hellenism. He told a meeting of the Greek synod of bishops that the crisis was “particularly grave” and acknowledged the need for “catharsis.” “I humbly ask for forgiveness from the people and the clergy, who, in their majority, honor…the cassock they wear,” Brian Murphy, the Associated Press’s European religion writer, quoted him saying on February 18.

The synod began accepting episcopal resignations, appointing investigative

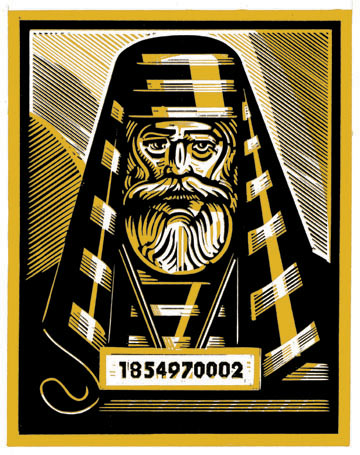

com- “[T]he archbishop of Athens and the various bishops who are mired in the heart of the church scandal have claimed in public, or in corridor talk, that the church is a target of sinister forces seeking to undermine its leadership,” snorted Kathimerini columnist A.I. Angelopoulos. “Even if one is to believe at least some of these accusations, it is nevertheless hard to ignore that the longstanding policies of the Greek Orthodox elite have themselves inflicted numerous wounds on the body of the church.” In mid-February, a public opinion poll published in the secular newspaper Eleutherotypia (Free Press) reported that Christodoulos’ approval rating had dropped from 68 percent last May to 43 percent. Other polls showed that most Greeks, for the first time, supported the separation of church and state. “The Orthodox Church has held a rarified position as the perceived caretaker of Greek identity during four centuries of Ottoman rule that ended in the early 19th century,” the AP’s Murphy wrote on February 18. “More recently, opinion polls often placed it among the most trusted institutions and Christodoulos was as popular as a celebrity.” For the Orthodox church, the most daunting aspect of the scandal was that the huge outpouring of accusations against bishops tends to confirm what many Greeks have always whispered about the church’s celibate elite—that their ranks are swollen with grifters, self-promoters, and hypocrites who publicly condemn extramarital sex and homosexuality while indulging freely themselves. While the crisis in Greece was more florid, the Jerusalem scandal exposed a geopolitical mare’s nest involving Greeks, Palestinians, Israelis, and Jordanians in a murky dispute centering on secret leases of property in the Old City of Jerusalem to Jewish businesses interests. At the center of the storm was Patriarch Irineos I, an ardent Greek nationalist committed to the preservation of Greek control of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem. “These days the gates of hell have opened and the darkness of lies, defamation and war against the mother church have emerged,” Patriarch Irineos complained to Greek journalists in February in the characteristic high-flown Greek ecclesiastical style. “Demons are circling the ways of the Holy City and trying to crush those who support the Jerusalem patriarchate and the brotherhood of the Holy Land.” The Jerusalem patriarchate is one of world’s dozen independent Orthodox churches, none of which has the right to intervene in any other. Five of these “autocephalous” churches have Greek identities: the churches of Cyprus and Greece and the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, whose communities are in fact Greek, and the patriarchates of Alexandria (Egypt and Africa), and Jerusalem, whose communities are not. The latter three are vestiges of pre-modern times when Greek communities flourished all over the eastern Mediterranean. As has been the case for hundreds of years, almost all of the roughly 100,000 Orthodox Christians in Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian territories—the Jerusalem patriarchate’s territory—are Arabs. Yet more than 100 of the patriarchate’s 120 clergy are Greek, and many of these are men shuttled from Greece into the Holy Land for relatively brief stints. The patriarchate itself is governed by a 17-member synod of bishops drawn exclusively from the exclusively Greek monastic Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulcher. The Brotherhood is widely viewed as a band of monastic plunderers, eager to skim off whatever sources of loot they encounter. Especially since 1967, when Israel seized the Old City of Jerus-alem from Jordan, there has been persistent tension between Greeks and Arabs over the ethnic character of the church. Viewed charitably, the Jerusalem patriarchate has been played for advantage by the various contending parties in the Middle East, each of which would like to gain control of its landholdings. One measure of the church’s plight is that the Israeli and Jordanian governments and the Palestinian Authority all have veto power over the election of the patriarch—a legal vestige of the Ottoman Empire’s style of controlling religious minorities. In late March, the Israeli daily Ma’ariv reported that the patriarchate, which holds billions of dollars worth of property in Israel and Palestinian areas of the West Bank, had secretly sold several symbolically significant properties just inside the Old City’s Jaffa Gate to Jewish investors from outside Israel. “Omar Square is Ours!” blared one Ma’ariv subhead. The issue inflamed longstanding Arab perceptions that the Greek hierarchy was colluding with Israel to erode the Arab presence in the Old City, which Palestinians want to see as the capital of an independent Palestinian state. Irineos “repeatedly denied” having sold the land, Greg Myre and Anthee Carassava reported in the April 4 New York Times. “But his claims have met deep skepticism, and the episode has touched some of the most sensitive nerves in the Holy Land…. Palestinians in the Greek Orthodox Church have renewed charges that the Greek clerics are out of touch with the Arab clergy and people.” The result was an explosion of Arab rage, articulated mostly by Arab Orthodox Christians (although the Palestinian Liberation Organization may have had a hand in organizing things) and focused on the ritual events of the week preceding Easter—Holy Week—when Jerusalem is flooded with Orthodox pilgrims. “Angry Arab protestors mobbed the Greek Orthodox patriarch during a religious procession in Jerusalem’s Old City on Sunday, enraged over a scandal involving the alleged sale of politically sensitive land to Jewish investors,” Agence France Presse reported on April 24. The attack took place when Irineos “emerged from the basilica of the Holy Sepulcher after a three hour service on Palm Sunday.” Scores of Arab members of his flock greeted him with cries of “Judas” and “Shame on you!” as they struggled with Israeli riot police and pilgrims from Greece and Cyprus. While Greek and Arab co-religionists squabbled over a sign that read: “Judas, betrayest thou the Son of Man with a kiss,” protestors spit on the patriarch and one of them lobbed a bottle of water at the hierarch’s head. Irineos, who became patriarch in 2001, was so shaken that he failed to turn up for the solemn services on Good Friday. And for the climactic services of Holy Saturday, Israeli security services prevented virtually all Arab Christians from attending. Denying any part in the land transaction, Irineos pinned the blame on his financial lieutenant, a 32-year-old Greek national named Nikolaos Papadimas, who had disappeared, apparently taking $800,000 in funds realized from the deal along with him. “May my hands be cut off if I have stolen,” Irineos told Kathimerini in mid April. But on Good Friday, April 29, Ma’ariv reported that it had obtained copies of a 198-year lease signed in August 2004 by Papadimas, as well as a power of attorney authorizing Papadimas to act on behalf of the patriarchate that Irineos had signed a few months earlier. The patriarch didn’t have persuasive response to that revelation, and, at about the same time, the Greek government reported that he had not cooperated with investigators sent from Greece. Meanwhile, the scandal in Athens and the scandal in Jerusalem had begun to merge. Through April, more and more attention focused on a shadowy freebooter named Apostolos Vavylis. A convicted heroin dealer, Vavylis often dressed in monastic garb although he was never a cleric, and consorted with the Greek and Israeli security services. Archbishop Christodoulos denied knowing the man, until a copy of a recommendation letter written by him in the mid-1990s surfaced in the press. In 2001, it seemed, Vavylis had shuttled between Athens and Jerusalem on a mission of “national importance,” he told journalists from a secret hiding place. During Holy Week, the Israeli daily Ha'artez reported that Vavylis claimed to have been assigned by Christodoulos to win Irineos’ election as patriarch of Jerusalem by hook or by crook. According to Ha’aretz, Vavylis claimed that Irineos had offered him $400,000 if he won, but then had welshed on the deal. In the meantime, Vavylis negotiated with Israeli officials on Irineos’ behalf and allegedly blackmailed other candidates for patriarch by threatening to publish photographs of their homosexual entanglements. At one point in April, Vavylis and Papadimas were both issuing regular statements to journalists from hiding places abroad. On April 23, Vavylis was tracked down by Greek police and Interpol in Italy, and he now promises to be a spectacular witness in prospective Greek trials. “In this religious themed reality show—where insults, rude gestures, threats and curses alternate with the hypocritical ‘Christ is Risen!’” wrote Panetlis Boukalas of Kathimerini. “It is difficult to distinguish who deserves the role of the Good Christian and who plays the traitor, thief or humbug. Insults, vanity, wild looks and self-righteousness are common to all. All invoke God, who sees all from high and apparently takes sides.” On May 5, a majority of the patriarchate’s synod of bishops, along with most of the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulcher, decided to clean house. Irineos, always a figure of controversy, was dismissed with a signed letter that said he was “incorrigibly caught up in a syndrome of lying, religious distortions, degradation of the Patriarchate, and irresponsible mishandling of Patriarchate property.” According to the Athens News Agency, the main Greek wire service, Irineos replied that his colleagues were “worms and trash,” and that the letter had no legal standing because only he could summon a meeting of the synod. He wanted to fire the members of the synod and replace them with sympathetic men.

A

standoff ensued after Irineos fled from the offices of the patriarchate and

holed up, with Israeli police protection, in his official residence. With

the Greek, Jordanian, and Palestinian governments calling for his

resignation and Greek newspapers running headlines like In Istanbul, meanwhile, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Bartholomew, asserted his right to act as the “first among equals” in the Orthodox world hierarchy and called a meeting of heads of all the autocephalous churches to decide how to respond to the crisis—the first such meeting in a decade. Bartholomew himself urged Irineos to resign, which his Jerusalem counterpart refused to do. Asked by Reuter’s correspondent Goran Tomashevic why he couldn’t control the damage more effectively, Patriarch Bartholomew responded, “I cannot work miracles.” When the global synod of Orthodox leaders met on May 24, it voted 10-to-2 to terminate intra-Orthodox recognition of Irineos and authorized the Jerusalem synod of bishops to elect a new patriarch. None of this moved Irineos, who attended the Istanbul summit and declared that he intended to remain in office. Outside of Greece and Israel, the whole saga attracted little journalistic attention, with most American papers carrying short and almost incoherent news briefs at junctures in the story’s development. Not until May did some more ambitious pieces begin to try to put the story in perspective. Most of these efforts sought to explain how the leasing of Old City land had come about. The Jerusalem Post, Israel’s English-language daily, shed the most light in a series of opinion pieces that proffered coherent interpretations of the roots of the struggle—notably a May 23 op-ed by Daoud Kuttab and a May 26 article by a Greek monk, Hieromonk Joseph, headlined “Better the Patriarch Than the Patriarchy.” Both pieces argued that the severity of the rebellion against Irineos had more to do with the possibility that the Palestinians and Israelis might patch up their differences in the relatively near term than with Irineos’ idiosyncrasies. With that end in view, Arabs hoped to seize control of the Jerusalem church, as their neighbors in Syria and Lebanon did in the 1890s in the Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch. With the patriarchate’s landholdings in Arab hands, Arabs might have real economic power to wield. Kuttab, in particular, held out hope that the incident would “allow Arab Christians to claim their rightful place” in the governing of the Orthodox Church in Israel and the Palestinian lands. “The Orthodox Church, the mother of all Christian churches in the Holy Land, is a very strange creature. Palestinian Christians consider it the last bastion of religious colonialism in the Holy Land.” Hieromonk Joseph, a priest monk who served in the Jerusalem Patriarchate from 1996 to 2002, offered a Greek take on the situation. The problem, he wrote, was a longstanding and corrupt tradition of authoritarian leadership in the Jerusalem patriarchate. The patriarchate’s structural weakness is that internal laws allow the election of its patriarch by a mere plurality of the synod of bishops, and not the majority required by all other Orthodox churches. This bred factionalism, and, indeed, in 1991, Irineos won election with only seven of seventeen votes, with each of two rivals getting five votes. The complications go deeper because many think that the Church of Greece and perhaps even the Greek foreign ministry acted behind the scenes, along with the Palestinian Authority, to support Irineos, who had long served as the Jerusalem patriarchate’s representative in Athens. The Israeli and Jordanian governments backed a rival. “Irineos’s fawning pre-election letters to Yasser Arafat found their way into the media,” Joseph wrote, and “the Israeli government vigorously opposed Irineos.” When he was elected, the Israeli government withheld its recognition of the validity of the election until 2004, and was still encouraging a legal challenge to the election in Israeli courts this spring. As Joseph and many other unnamed sources read it, Irineos had struck a deal with the Israeli government to lease symbolically important Old City property to Jews in exchange for Israeli government recognition of his election. The deal would also produce a substantial flow of cash to relieve the patriarchate’s chronic deficits—and perhaps to line the pockets of Irineos’ faction. Another key problem, the monk wrote, was Irineos’ obdurate Greek nationalism. “In the very first speech at the enthronement ceremony, Irineos advanced a radical nationalist program, insisting on the purely Greek nature of the patriarchy; moreover, he was going to enhance that character by inviting more Greeks to move to Israel.” Patrick Theros, a retired U.S. diplomat active in Greek-American affairs, painted a similar picture in the May 21 edition of the Greek-American newspaper, the National Herald of New York. “It now turns out that Irineos made certain injudicious promises to Palestinians that, in return for their support, he would terminate or otherwise undo the leases for the Israeli Knesset, the King David Hotel, and other important Israeli institutions which sit on Patriarchate-owned land.” Theros claimed that Irineos lacked the street savvy of his predecessor Diodoros, “a wily politician who protected Orthodox control of the Holy Places through judi-cious diplomacy with the Israeli, Jordanian, and Palestinian governments; a diplomacy which was frequently reinforced by an equally judicious use of corruption.” As May closed, the Greek government was looking for ways to pressure Irineos to “retreat to a monastery.” It threatened to withdraw his Greek diplomatic passport, and, indeed, publicly reissued his passport, listing as Irineos’ occupation: “ex-patriarch.” Back in Athens, the main public question seemed to be whether Arch-bishop Christodoulos could cling to office, in spite of the fact that many of his closest associates had been discredited. But as the summer rolled around, the besmirched hierarchs could not be counted out. There were, indeed, indications that the Greek people had wearied of the spectacle. In a May 13 opinion survey, 80 percent said they expected that corruption would always be a problem in the Greek church. Hellenism and Orthodoxy remained bound at the hip, and it was time to move on.

|