|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Table of Contents Fall 2003

Quick Links: From the Editor:

Special Supplement: The Social Gospel Lays an Egg in Alabama Mel Gibson, the Scribes, and the Pharisees Gibson and Traditionalist Catholicism

|

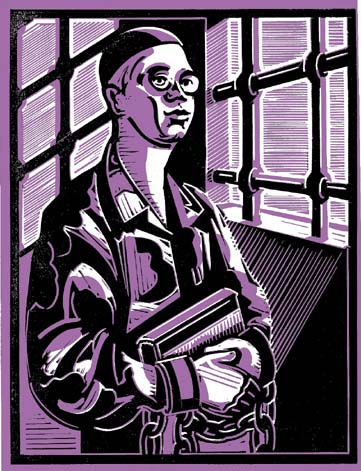

The Case of Chaplain Yee

Yee was the golden boy of the armed forces’ new Muslim chaplaincy program, a public spokesman on Muslims in the military and Islam generally. “The taking of civilian lives is prohibited by Islam,” he told Scripps Howard a month after the September 11 attacks, “and whoever has done this needs to be brought to justice, whether he is Muslim or not.” After being sent to Guantanamo, Yee was commonly offered by the military for interviews with reporters. Now, it seemed (as the headline on Edward Plowman’s October 4 article in World magazine put it), “We hardly knew Yee.” Like John Walker Lindh, “the American Taliban,” here was another story of a religious turncoat [see “The Real Man Without a Country,” Religion in the News http://www.trincoll.edu/depts/csrpl/RINVol5No2/lindh.htm], but this time the protagonist was a prototypical All-American immigrant youth. Chinese American, raised Lutheran in New Jersey, “Jimmy” was a cub scout, played Little League baseball, and wrestled in high school. He went to West Point. “The kid had a good Christian upbringing, a steady suburban upbringing,” his childhood pastor Remo Madsen told Ralph Ortega and Derek Rose of the New York Daily News September 22. “He went to church, he learned about Christ, he went to Sunday school, he had terrific societal values.” Madsen, they reported, “could not understand why Yee converted to Islam.” For his part, Yee saw his conversion, which took place during military service in Egypt after the Gulf War, as an extension of his Christian upbringing. “It didn’t throw out what I believed of Jesus Christ,” he told the Seattle Times shortly after 9/11. “We believe Jesus was sinless, that he performed miracles, was born of Mary, and that he will come again. So my beliefs in Christianity didn’t go away; Islam held these beliefs.” Although this statement was published repeatedly following his arrest, the prevailing story line was of a good boy gone bad. Rowan Scarborough, who broke the story in the Washington Times September 20, set the tone of virtually all subsequent coverage by emphasizing Yee’s apparent duplicity. The Yee who publicly portrayed Islam as a “religion of peace,” Scarborough wrote, had joined “three other notable detainees in the war on terrorism” in the Charleston, South Carolina, brig: “Yaser Esam Hamdi, an American-born Saudi who fought with the Taliban; Jose Padilla, a former Chicago gang member who is charged with plotting to detonate a radioactive bomb; and Ali Saleh Kahllah al-Marri, accused of being an al Qaeda sleeper agent.” Yee’s high school wrestling coach, Richard Iacono, was widely quoted to the effect that Yee had demonstrated a change of character when he returned from service in the Middle East. After spending a few months as a pharmaceutical salesman, he quit to study Islam and Arabic in Syria. “Right then, I thought, uh-oh,” Iacono told the Daily News’ Ortega and Rose September 22. “I have to believe in my kids,” Sarah Kershaw of the New York Times quoted him as saying September 24. “But if that religion has brainwashed him to change his thinking, then maybe I’m wrong.” The good “James” stood in contrast to the apparent terrorist sympathizer who, virtually all the early stories claimed, had taken the “Muslim name” Youseff. This prompted his wife (who on the advice of her lawyer had at first refused to speak to reporters) to tell Kershaw, who wrote the most balanced of the many Yee profiles, “It’s not true—he never changed his name. He likes his name.” She explained that she called him Youseff because that was her father’s name and she found it easier to pronounce. But the explanation didn’t keep the media from referring to him as “James, also known as Youseff” and “James ‘Youseff’ Lee.” A few stories—but only a few—expressed doubts that the fact that Yee had reportedly been found in possession of names of prisoners and interrogators and diagrams of the Guantanamo facility meant that he had turned against his country. On September 24, CNN security analyst Kelly McCann reported that senior officials she had spoken to described the press coverage as “Islamic hysteria.” She went on to ask, “Are we over-reporting this? Are we making too much of it?” “[N]one of the reports suggested how detailed the diagrams were, and maps depicting the layout of the Guantanamo base are routinely handed out to reporters,” Dan Fesperman of the Baltimore Sun wrote September 25. “All of this could mean either that Yee is a great actor or the victim of overzealous investigators.” Since soldiers at Guantanamo must sign agreements not to reveal details about the camp, “even the simplest breach of security might be interpreted as a criminal violation.” Some raised the question of whether the chaplain’s job was itself at odds with the interrogation process. Findlaw columnist Phillip Carter, writing for CNN.com, explained that isolation and dependence are key to the interrogation process: “A detainee who’s alone, disoriented, and afraid will likely turn to his interrogator for help—assistance that can be bought with the currency of information.” A kind word from a guard, translator, or chaplain can disrupt this relationship and interfere with the interrogation process, he wrote. “If Yee and Halabi indeed…acted as friendly counselors to, couriers for, and…procurers of food for, the detainees,” he continued, “then it is very likely that they fatally sidetracked interrogation.” The consensus view, however, was that the problem lay in the vulnerability of the Muslim chaplaincy program to infiltration by Islamic radicals. Washington Times columnist Frank Gaffney Jr., indulging in a bit of I-told-you-so, reminded readers September 23 that after the grenade attack by U.S. Army Sgt. Asan Akbar at the beginning of the Iraq war he had written that Akbar “could have gotten murderous ideas about America, its armed forces and the Muslim world from a chaplain in the U.S. military.” The same day, the Times’ Steve Miller and Rowan Scarborough, citing criticism of the Pentagon’s screening policies, asserted that “the military had seen evidence that some chaplain’s officers had referred those interested in Islam to a Web site containing links to the speeches and writings of radical Wahabbi clerics who promote violence against Israel and the West.” On September 23, as well, the Washington Post’s John Mintz and Susan Schmidt recalled a story the Post ran months before in which New York Senator Charles E. Schumer had requested an examination of the process of vetting Muslim chaplains, pointing out that both organizations used by the military to endorse candidates had been investigated in 2002 as part of a probe of Muslim organizations alleged to have dealings with terrorists. “It is disturbing,” Schumer told Ray Rivera and Cheryl Phillips of the Seattle Times, also on September 23, “that organizations with possible terrorist connections and religious teachings contrary to American pluralistic values hold the sole responsibility for Islamic instruction in our armed forces.” Within the week, Schumer and Arizona Senator Jon Kyl had announced plans to hold a Senate hearing on the chaplain vetting process. Doubts about the vetting process seemed to be justified when, at the end of September, a leader of the American Muslim Council, Abdurahman Alamoudi was arrested for illegally accepting money from Libya. Reports indicated that the council was closely connected to one of the organizations that approves Muslim chaplains. At the October 14 Senate hearing, John S. Pistole, Assistant Director of the FBI Counterterrorism Division, noted that radical groups, including domestic terrorist groups such as the Aryan Nations, have historically looked at the U.S. military and prisons as fertile recruitment and training grounds. As of early November, Yee faced only minor charges for improperly handling classified information—specifically (as Knight Ridder’s Carol Rosenberg reported October 13) “taking classified material to his home” and “transporting classified material without the proper security containers.” Then, on November 25, AP’s Paisley Dodds reported that new charges of adultery and storing pornography on government computers had been filed against Yee. However, it is still possible that the Guantanamo Bay prison commander could dismiss the charges entirely. That, at least according to World magazine—an evangelical Christian publication that advertises itself as “God’s World News”—is what happened to Yee’s predecessor at Guantanamo, Navy Lt. Abuhena Saiful-Islam. A “highly placed Pentagon source” told World that Saiful-Islam had been “taken into custody on similar charges about a year ago” but was cleared in the absence of “chargeable evidence” and returned to his home base at Camp Pendleton. On October 24, the Washington Post’s Mintz reported that military authorities had launched their investigation of Yee nearly a year earlier, after “a series of confrontations between him and officials” over the treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo. As Jim Stewart put it on the CBS Evening News September 22, “In the end that may be all that Yee is guilty of, being too sympathetic to the men he ministered to.” Yee’s successor is unlikely to face this problem. “[W]hile the new chaplain will continue Yee’s role of advising command staff on Islamic practices, he will minister only to Muslim soldiers and will not meet with detainees,” reported the Boston Globe’s Charlie Savage November 7. A Christian chaplain, Maj. Dan O’Dean, will instead handle the religious requests of detainees.

|

In

the military’s investigation of security breaches at its Guantanamo Bay

prison, the most serious charges were leveled at two translators—USAF Airman

Ahmad al-Halabi and civilian Ahmed Fathy Mehalba. But it was the arrest of

Captain James Yee that caused all the fuss.

In

the military’s investigation of security breaches at its Guantanamo Bay

prison, the most serious charges were leveled at two translators—USAF Airman

Ahmad al-Halabi and civilian Ahmed Fathy Mehalba. But it was the arrest of

Captain James Yee that caused all the fuss.