|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Table of Contents Summer 2003

Quick Links: From the Editor The Latest Japanese Cult Panic

|

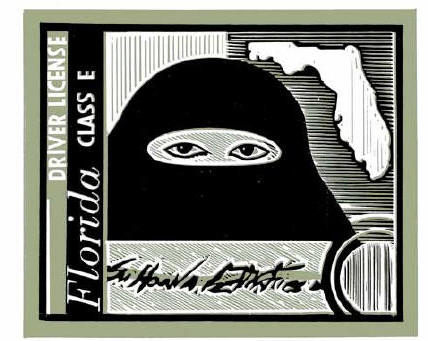

Jihad for

Journalists Wartime always brings conflicts between national security and individual rights, but it is not usually journalists who in the name of security lead the charge against religious freedom. That’s what happened in the case of Sultaana Freeman, a Florida Muslim who filed suit for the right to keep a photo of herself wearing a veil on her driver’s license. The story began in January, 2002, but its roots lie in the fall of 2001, when the Florida Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles undertook a general review of its driver’s license system because a number of 9/11 hijackers had obtained valid Florida licenses. The veil issue was first raised in the media in a Miami Herald article on November 23, 2001 entitled, “Tighter Security May Mean More Strict Driver’s License Rules.” Freeman, an American convert to Islam, wears a niqab: a veil that hides all of the head and face, revealing only her eyes. When she moved to Florida in early 2001 she applied for and received a driver’s license with a picture of her wearing it, just like her previous license in Illinois. Florida recalled the license in December, citing security issues and the necessity of full-face photographs to identify all drivers. Freeman was ordered either to retake the photo without her niqab or face having her license revoked. She refused and the state followed through on its threat. She turned to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which on January 17 filed a petition to have her license reinstated on the grounds that the state had deprived her of her right to religious free exercise under Florida law. “I don’t show my face to strangers or unrelated males,” Freeman declared in a January 30 article in the Orlando Sentinel by Amy C. Rippel and Pedro Ruz Gutierrez. After a brief flurry of coverage, the case disappeared from view for several months awaiting its first day in court. On June 27, 2002, just before a hearing on the state’s motion to dismiss, Freeman’s attorney Howard Marks told the New York Times that veiling was “a fundamental tenet of her religion and to require her to sacrifice having a driver’s license or choose between that and her religious belief is a violation not only of Florida’s Religious Restoration Act but also of the Florida Constitution.” Passed in the mid 1990s at the behest of a large coalition of religious actors, including many on the Christian right, this Religious Freedom Restoration Act (one of many state versions of a Clinton era federal law) requires that the state demonstrate a compelling interest whenever it restricts the religious behavior. According to Jay Vail, a Florida assistant attorney general, there was just such a compelling interest in this case. “Florida law is unequivocal that a photo ID is required,” Vail said July 30 on the National Public Radio show All Things Considered. “It’s very plain in the law.” He also told United Press International that, “when there is a matter of common interest that promotes public safety, then we must yield on our right to free exercise to the extent that it’s necessary to secure that public safety interest.” On May 27 of this year, the suit went to trial before Florida Circuit Judge Janet C. Thorpe amidst a full-throated media frenzy. On June 6, Thorpe ruled that while Freeman’s religious belief was sincere, Florida’s demand that she lift the veil did “not constitute a ‘substantial burden’ on her right to exercise her religion.” The state’s need to identify drivers outweighed her need to cover her face, the judge said. In finding that Freeman was “motivated by a sincerely held religious belief to remain veiled.” Thorpe evaluated her rights claims carefully and respectfully. The same cannot be said for most journalistic analysis. While news stories usually recounted the legal arguments in a straightforward way, editorial writers, columnists, and TV pundits vied with one another to minimize the complexity of the legal arguments and to demean Freeman’s religious beliefs and stigmatize Muslims. Michael Ramirez’s May 29 cartoon in the Los Angeles Times portrayed the driver’s licenses of Freeman and her lawyer, listing her address as “Silly Lawsuit Way” and the lawyer’s name as “Bunch O. Clowns.” “The nuts and bolts of this case have nothing to do with Ms. Freeman’s right to worship, freely or diversely, and everything to do with her responsibility to drive lawfully,” Washington Times columnist Diana West wrote May 30. “On the highway, she is a driver first, not a Muslim.” West went on to insinuate that denying Ms. Freeman the right to drive altogether might keep her from becoming a suicide bomber. On May 31 the Chattanooga Times Free Press’s Steve Barrett compared Freeman to “a member of the Ku Klux Klan insisting that his driver’s license photo be taken while he wore a Klan hood that hid his face.” In her June 15 column, Susan Martin of the St. Petersburg Times dismissed Freeman as “a misguided individual embracing an extreme form of Islam.” If editorial writers were less likely to trivialize Islam, they were equally cavalier about legal precedent and just as dismissive of Freeman’s right to sue. “Score one for common sense,” The Dallas Morning News declared June 10. “Driving is a privilege, not a right. ” Through the entire debate, journalists seemed unable to grasp that there has been a great deal of litigation over driver’s licenses, and that states have granted many exemptions to those who don’t want photographs on their licenses. Three times since 1978, different state supreme courts have issued decisions supporting plaintiffs who didn’t want photographs on their licenses at all (Bureau of Motor Vehicles v. Pentecostal House of Prayer (1978, Indiana), Quaring v. Peterson (1984, Nebraska), and Dennis v. Charnes (1984, Colorado). In each case, the courts directed the state to provide exemptions for those citizens who objected to having their pictures taken on religious grounds. All three cases involved Pentecostal Christians, some of whom regard it as religiously impermissible to subject themselves to photography. Fourteen states (Arkansas, California, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, Oregon, South Carolina, Vermont, and Wisconsin) have rules providing an exemption from photo requirements when a licensee’s religious precepts do not allow him or her to be photographed. Judicial decisions in other states, including Colorado and Nebraska, require such an exemption. The ACLU pointed this out in interviews and during the trial itself, and Judge Thorpe’s ruling acknowledged as much. But the media weren’t interested. Among many thundering editorials, the Herald-Sun of Durham, North Carolina, the Herald of Rock Hill, South Carolina, and the Denver Post commended Florida for lifting Freeman’s license without mentioning that their own states require alternate forms of driver’s licensing when religious objections are made. The worst offenders were the hosts of cable news talk shows. Even when they interviewed legal experts, they usually cut short discussions of the legal landscape in order to move on to their own misconceptions. “Driving is a privilege not a right,” pronounced Chris Matthews on May 29, host of Hardball MSNBC, as he cut off Howard Simon, executive director of the Florida ACLU, who was attempting to explain that, legally, it’s not that simple. In her decision Judge Thorpe cited the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1963 Sherbert v. Verner decision, which held that the distinction between a right and a privilege does not matter when the privilege is part of “normal life activities” like driving. On June 20 civil liberties attorney Chris Murray discovered the futility of attempting to confound Fox News Network’s Bill O’Reilly with mere facts. O’Reilly brushed off Murray’s attempt to correct the “driving as a privilege” interpretation, and ignored Thorpe’s ruling that it was “immaterial whether Plaintiff is in the majority or minority of any given sect of practicing Muslims.” Instead, O’Reilly cited as relevant a UCLA law professor’s statement that there is no Islamic law prohibiting believers from being photographed. Indignation drove almost all the very emotional opining on Freeman’s lawsuit, which was neither outrageous nor even unusual. Aside from a few news stories, journalists were unwilling to acknowledge that exceptions to mandatory photograph requirements are commonly granted in the United States (although not, perhaps, in Florida). Ignoring the legal realities, they preferred to shout down Freeman’s attempt to exercise her religion as “extremist,” “frivolous,” “foolishness,” and above all, not worth a court’s time. On CNN’s “Attorney’s at Law” show June 1, Lisa Bloom of Court TV asked plaintively, “[D]on’t the Muslims have the same rights as Jews, for example, who have the right to wear a yarmulke in the military? Nuns to wear a habit? Replied CNN contributor Michael Smerconish: “They did up until September 10, and then all of a sudden, everything changed.”

|