|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Table of Contents Summer 2003

Quick Links: From the Editor The Latest Japanese Cult Panic

|

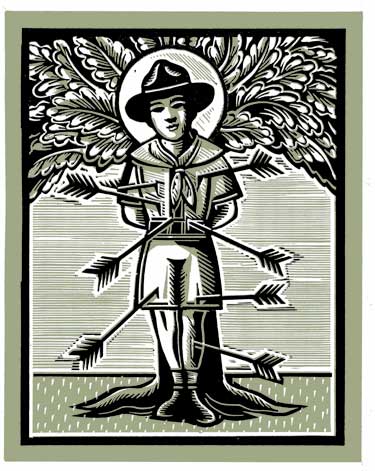

The Irreverent

Eagle In his new book on the Boy Scouts, Scouts Honor, New York Times deputy metropolitan editor Peter Applebome recalls a local Methodist minister offering a prayer that his son’s mostly Jewish troop in Chappaqua, N.Y. would have a successful day selling Christmas trees to raise funds. “It struck me,” he writes, “that other than the beautiful renderings of the Scout oath (‘On my honor I will do my best to do my duty to God and my country…’) this was the first reference to God in any form since we had joined the troop.” So much for the discreet ecumenism of the Middle Atlantic. In other parts of the country God, who has become almost as big a problem for the Scouts as gay scoutmasters, is treated differently. Take the case of Darrell Lambert of Port Orchard, Washington. Last fall the 19-year-old Eagle Scout was kicked out of his troop for publicly announcing that he was an atheist. Marsha King reported the story for the Seattle Times Oct. 29 in a point-counterpoint story that alternately quoted Lambert and Brad Farmer, head of the Chief Seattle Boy Scouts Area Council. Lambert was, according to King, the straightest of straight arrows. He didn’t smoke, use drugs, or imbibe alcohol, and in his senior year of high school alone had completed over 1,000 hours of community service. King even quoted the parent of a fellow scout as saying, “Darryl walks the walk of Christ. Whether he professes it or not, he walks it.” What he did profess didn’t get him in trouble at first. After proclaiming his lack of belief at his Eagle review board, the board—apparently expressing local standards— praised him for his honesty. It was only after he doing the same at a regional leadership seminar that red flags went up. Farmer gave him, King wrote, “about a week to decide ‘in his heart’ if he was truly an atheist.” It seems that the young man’s real sin was not so much saying what he believed as his insistence on calling it atheism. “I think the only higher power than myself is the power of all of us combined,” Lambert told King. “We’re all in symbiosis with each other.” That was not a very far cry from Farmer’s interpretation of the Scouts’ requirement of “Reverence”: “It can be part of subscribing to a structured religion—or a more amorphous faith in some presence greater than ourselves.” Such expressions of amorphous spirituality are, if anything, the norm in the Pacific Northwest. And Lambert’s goal was to make his case for local standards into a cause célèbre. “The way I want to see the Boy Scouts change is to take membership laws away from national and return them back to the individual units,” he told King. The vast majority of the media recognized this for the test case it was. It took only a few days for the Scouts to prepare their response. In Dean Murphy’s Nov. 3 New York Times story, Mark Hunter, director of marketing and administration for the Seattle Council, and national spokesman Gregg K. Shields challenged the idea that Lambert walked on water. Hadn’t the Eagle Scout repeatedly sworn an oath to do his duty to God? “It would be a disservice to all the other members to allow someone to selectively obey or ignore rules,” Shields said. As for the 11 points of the Scout Law besides reverence, Murphy wrote as the kicker to his story, “Mr. Shields could not say whether anyone had been ejected for being untrustworthy, disloyal, unhelpful, unfriendly, discourteous, unkind, disobedient, cheerless, unthrifty, cowardly or sloppy.” The deadline having passed without Lambert changing his mind, the council issued an official statement of expulsion, from which the Seattle Times extracted this befuddled passage: “We regret that Mr. Lambert feels his beliefs must be compromised; that is never requested or desired by the BSA. The Boy Scouts of America is a shared value organization and we do not ask anyone to compromise their beliefs just to become a member.” For his part, Lambert pledged to appeal the ruling up the BSA ranks. After the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2000 that the BSA could maintain its ban on gay scoutmasters, newspapers across the country predicted that the organization’s troubles were far from over. Since then, 50 United Way chapters (five percent of the total) have withdrawn their funding, and numerous private institutions have barred their doors to the Scouts. Meanwhile, the national BSA has withdrawn recognition from some troops and local councils that have publicly admitted gays. The Lambert case promised more of the same. In a Nov. 10 article for the Buffalo News, former Eagle Scout and professional atheist David Carter called on the BSA simply to come out of the closet as a religious organization. “Sure, that might leave the BSA a mere shell of its former self, with little more than pious ideas and two Bibles to rub together for warmth,” Carter wrote. “But that way the BSA couldn’t be accused of hypocrisy—claiming itself a private club to justify discrimination while raking in congressionally imposed taxpayer dollars, perks and sponsorships.” On Nov. 17, another former Eagle Scout, the Washington Post’s Rick Weiss, explained his decision to mail his Eagle Badge back to the BSA. “Why would the organization demand such a rote expression of religious faith when it’s in a position to cultivate the real thing from scratch?” Weiss asked. “That’s how it worked for me. On windswept mountaintops and in snow-muffled woods, in moments alone and then together again with my fellow campers, I got religion in spades. But apparently not the kind that counts.” With Lambert’s five-page appeal to the BSA gathering dust at national headquarters, the story gendered itself. In a Dec. 25 article, Lisa Foderaro of the New York Times highlighted the ways in which the Girl Scouts have used a new feminist energy to update their curriculum to “modern norms” from a merit badge in car repair to a more tolerant view of homosexuality. “As for Religion,” Foderaro wrote, “a member can substitute her own word for God in the Girl Scout promise.” On Feb. 16 the Seattle Times’ Nancy Bartley wrote a similar story that was later run by the Charleston (W.V.) Gazette under the predictably apropos title, “Outside the Cookie Box, Girl Scouts more flexible.” On Feb. 28, the Seattle Times caught up with Darrell Lambert distributing pamphlets outside the Chief Seattle Council’s 24th annual “Friends of Scouting Breakfast” fundraiser at the Washington State Convention and Trade Center. Lambert was now a founding member of the Northwest Coalition for Inclusive Scouting, and was seeking to persuade some 2,200 benefactors to hold back their donations. But what may fly in Seattle might never get off the ground in, say, Salt Lake City. On July 19 Salt Lake Tribune columnist Robert Kirby tried to answer a Mormon reader who asked whether one of his church’s leaders was right in saying that “failure to contribute $50 to the Boy Scouts of America really meant that he did not have a testimony of Jesus Christ.” “Think about it this way,” Kirby wrote. “It is supposedly the Lord’s church. The LDS church has adopted Scouting as part of its program for young men. Ergo the Lord is Supreme Scoutmaster. If Scouting needs money, it’s the same thing as the Lord needing it. And who would be too cheap to give Jesus 50 bucks?” Back on Nov. 6, Seattle Times columnist Bruce Ramsey warned, “If scouting gets out of synch with mainstream American values, it will die.” But which values are we talking about? And which mainstream?

|