RELIGION IN THE NEWS |

|

| Table

of Contents Fall 2002 Quick Links: Choosing Up Sides in the Middle East |

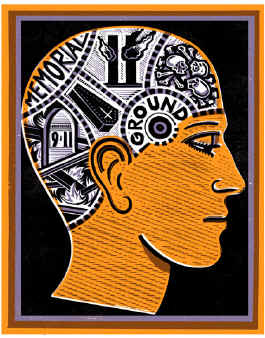

9/11 on Our Mind By Gary Laderman

At first glance, most journalists who produced stories this September 11 and 12 focused on local acts of public worship and memorialization, individual stories of tragedy and triumph, and speculative musings about how, or if, 9/11 changed American life. But upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that what they zeroed in on were the dead and what their deaths mean to the nation. Consider the Houston Chronicle’s coverage. On September 12, the newspaper canvassed many of the local events commemorating the anniversary in a story headlined "Thousands Crowd Places of Worship to Find Solace." Most of those interviewed expressed the need to give the dead—and their God—their due, an especially difficult task given the brutal circumstances of the day. Like so many articles, the Chronicle story wove the lives of individuals struggling with the memories of these vicious acts into the larger tapestry of national community and collective remembering. "Thousands of Houstonians joined Americans nationwide in crowded houses of worship and outdoor ceremonies Wednesday, seeking community and healing. ‘It is a day that is unforgettable,’ said Paula DeLeon Vargas, who rode a bus to Sacred Heart Co-Cathedral to pray. ‘It is for all the people who were lost. For all the families that God give them fortitude. God is the only one who can give them the strength to continue.’" In Buffalo, too, expressions of personal sorrow and the public rituals that bound the community together—and to the rest of the nation—radiated from memories of the dead, memories that many believed would transform the nation. "Everywhere you went, people spoke of the need to honor those who died," Phil Fairbanks wrote in the Buffalo News, "and even more important, to never, ever forget what happened on Sept. 11, 2001, the day that changed all of us—forever." A CNN roundup headlined "Americans Remember 9/11 in Many Different Ways" on September 11, conveyed the diversity of commemorative rituals. Examples included a moment of silence at 9:11 p.m. at Major League baseball games, a riderless horse parading in Helena, Montana, and the widespread interfaith services throughout the country. The tone of this dispatch—and many others like it—that called attention to the sacrifice of the dead was respectful and honorific, consciously attempting to bring dignity to thousands of people who died in the most undignified circumstances by linking their fate to the fate of the nation. Many pieces, like Don Collins’ story for CBSNews.com on September 11, suggested that through commemoration the nation might recapture "at least a part of the magical spirit that brought the country so closely together in the days, weeks, and months following the attack." But perhaps the most distinctive and telling aspect striking aspects of this anniversary commemoration was the immense significance accorded to the material remains of the World Trade Center—to the residue of decimated buildings and annihilated bodies mixed together and thus transformed into sacred ruins. According to CNN, small samples of this material have been transported to cities throughout the nation for ritual purposes. In San Clemente, California, for example, "surfers in a competition were to paddle into a circle and sprinkle Ground Zero dust in the Pacific Ocean." A monument that included "hundreds of pounds of contorted metal from Ground Zero" was unveiled in Eastlake, Ohio. Ground Zero, these rituals showed, is not merely a sacred location. Its meaning is so powerful that it cannot not be contained at the site, nor kept from Americans who felt emotionally and spiritually attached to the very dirt and rocks that remain where the Twin Towers once stood. "Even dirt is hallowed as loved ones collect scraps of memories," the New York Post reported on September 12. "They brought their grief and love, and they left with a handful of stones, a bag of dirt or a scrap of metal." The Post story then suggested that "hallowed earth of the World Trade Center site" played such an important role because of a particular cruel dilemma faced by a grieving nation: So few bodies were recovered from the killing field. The destruction in that spot was so complete, even the perpetrators’ bodies were reduced to nothing, to "zero," and thereby rendered symbolically powerless in the religious transformation of the land into a sacrosanct spot of national memory and rejuvenation. Ground Zero became a sacred site that simultaneously remains in New York and can be transported to other parts of the country. The proposed 9/11 memorial in Texas, a granite and steel monument incorporating beams from the rubble at Ground Zero, illustrated the process. "We want people to feel the relics that were washed in the blood of innocents," the Dallas Morning News quoted the architect. "We want people to recognize the horror, understand the sorrow, the righteous wrath, the resolve and remembrance." In spite of the feeling that this day was unparalleled in American history, a few news reports included various efforts to think about 9/11 in familiar, time-tested terms. The Houston Chronicle quoted Virginia Van Cleave, president of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, who placed the dead of 9/11 into another well-known mythological landscape in the Southwest: the Alamo. "How appropriate it is that we should be conducting this commemoration at a place where another group of common people made the ultimate sacrifice for freedom." Van Cleave put her finger on another key characteristic of the anniversary: the rhetorical effort to transform innocent, unsuspecting civilians into national heroes who sacrificed their lives—implicitly comparing them with American soldiers who died fighting for the country in wars past. This popular strategy aimed to reassure the united nation that these deaths were not meaningless, and that American justice will prevail. A Los Angeles Daily News editorial entitled "Uniting America: Renewing the National Resolve" caught the dynamic. "The nation grieved Wednesday for the 3,025 innocent victims of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, and today marks an anniversary of another sort. It was on this day a year ago…that we steeled ourselves with a new sense of resolve, a resolve to defeat our enemies and prevent another atrocity. As we mark that anniversary, we must renew that resolve." The rest of the editorial reiterated many of the explicit and implicit messages communicated by President George W. Bush during the day of national mourning: the dead will be avenged, and the nation will ultimately triumph over evil terrorists. Bush and his speechwriters understood the vital links between the body politic and the blood of martyrs, a strikingly religious theme throughout American history, but most powerfully articulated by Lincoln in the Gettysburg Address—a sacred text recited during the memorial services in New York City. In the president’s remarks at the Pentagon, the 9/11 dead were front and center as inspirational touchstones for the continuing war on terrorism: "Their loss has moved a nation to action, in a cause to defend other innocent lives in the world…. In every turn of this war, we will always remember how it began, and who fell first." And later in the day at Ellis Island, after musing philosophically about the shortness of our days here on earth, he emphasized the same political, and deeply religious, point about these inspiring martyrs: "We resolved a year ago to honor every last person lost. We owe them remembrance and we owe them more. We owe them, and their children, and our own, the most enduring monument we can build: a world of liberty and security made possible by the way America leads." On the anniversary, very few people found fault with Bush’s remarks and public acts memorializing 9/11. Within a short time, however, editorials appeared in some media outlets criticizing the day’s events, speeches, and silences. On September 19, Lyon College politics professor Bradley Gitz wondered in a column for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette whether he was "the only one who found last week’s commemoration of Sept. 11 a wee bit excessive and syrupy, perhaps driven a tad too much by television melodrama and choreographed sentiment?" Writing in the September 20 Washington Post, columnist Michael Kinsley rejected Bush’s insistence on a global struggle between good and evil as a simplistic and inappropriate response to the tragedy: "There are many groups of people, unfortunately, who would be happy to hijack four airplanes, fly them into crowded buildings and kill 3,000 Americans. In terms of malign intent, they are all evil. But only one of them managed to do it. The concept of evil tells you nothing about why—among the many evils wished upon the United States—this one actually happened. Nor does ‘evil’ help us figure out how to stop evil from visiting itself upon us again." Yet America has always relied on invocations of the dead to define itself and its mission in the cosmos. For Bush and numerous journalists attuned to the value of promoting social unity and common cause, our understandings of the dead and interactions with them bind us together and reflect national commitments to act appropriately in the face of atrocities. But the history of death in America is full of conflict as well as consensus, division as much as solidarity. Think of the widespread pillaging of Native American graves, the urgent politicizing of the Civil War dead (on both sides), the divisive quarreling over the questionable sacrifices in Vietnam—in addition to the ongoing efforts to recover the remains of soldiers missing in action, to name only a few examples. And today, too, some are raising questions about what the dead mean to our nation, and challenging dominant political views of how to respond to their deaths. On September 24, the US Newswire reported that an organization called September 11 Families for Peaceful Tomorrows, with members from a number of states, refused to accept the president’s position that the dead should inspire the living to engage in further acts of violence. "I am disappointed that the Bush administration has used the crimes of September 11 as a reason to invade Iraq, a nation with no proved connection to the terrorist attacks that took my brother’s life," said one member. "I believe the best way to honor the dead is by seeking justice through non-violent means, not by starting new wars." In another public defiance of the president’s take on the appropriate response to these events, a bumper sticker reads, "Our Grief is Not a Declaration of War." The conflict over how to live with this grief and what actions can salve the deeply traumatic memories of that day of death and destruction is only beginning to surface in this time of war. The contests over the meaning of the dead—a recurring symbolic struggle with profoundly high stakes, especially in times of crisis—suggest that automatic assumptions about collective solidarity often gloss over real divisions. The dead who lie beneath our feet and animate our spiritual lives do not always rest in peace. Instead, they can return to our consciousness to challenge our assumptions about political and military decisions, inspire resistance to the dominant interpretive strategies that anchor their meaning in a particular ideology, and fuel the passions of survivors who will not stand idly by while their memories are exploited. Whatever happens in Iraq, or with the war on terror, Bush’s words promising to the dead a world of liberty and security will probably define his legacy in U.S. history. The recent election suggests that his reliance on the symbolic power of the dead, and more importantly the presence of an evil dictator in our midst, resonated with a large swath of the American public. However, the lingering and troubling questions of what these dead mean to national identity, and whether they can energize popular support for military strikes aimed at even greater bloodshed have yet to be fully answered. |

News reports of

the thousands of ceremonies that commemorated 9/11 around the country

highlighted a distinctive and deep-rooted feature of national life: the use

of communal rituals to create social solidarity by invoking those who have

died. For, despite the conventional wisdom about America as a death-denying

culture, our history is riddled with examples of obsessive interest in, if

not downright cultic activity surrounding, the bones of the dead.

News reports of

the thousands of ceremonies that commemorated 9/11 around the country

highlighted a distinctive and deep-rooted feature of national life: the use

of communal rituals to create social solidarity by invoking those who have

died. For, despite the conventional wisdom about America as a death-denying

culture, our history is riddled with examples of obsessive interest in, if

not downright cultic activity surrounding, the bones of the dead.