|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links:

SpiritualPolitics

From the Editor:

|

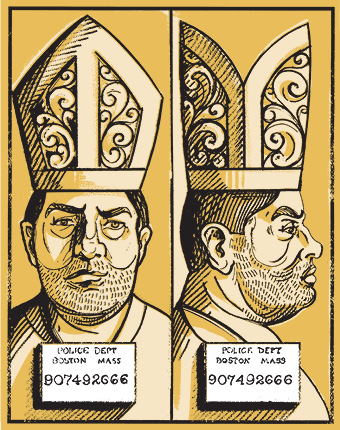

Bishops in the

Dock

How goes the struggle to reform? Not so well, at least according to prosecutors in Kansas City and Philadelphia. In 2011, for the first time in American history, criminal indictments were pressed against high church officials for failing to report suspected child abuse and child endangerment. In both cases, the charges deal with administrative decisions made by church leaders in the recent past, not old cases dating decades back. Both trials are expected to begin this spring. Why, despite the largest, longest scandal in the history of religion in America, are some Catholic bishops still struggling to evade or escape legal requirements that they automatically call the cops whenever clergy are accused of sexual misconduct? One plausible answer is that old habits die hard. For the last 1,800 years, the Catholic Church has pretty much consistently argued that its bishops have the exclusive right to discipline their clergy, a standard that entered Roman law as early as 412, when the Emperor Theodosius II agreed that only bishops—and not imperial courts—should prosecute and punish clergy accused of crimes. That privilege expressed the church’s evolving sense of the ideal church-state relationship—one that established powerful, state-supported churches, but simultaneously safeguarded ecclesiastics and the church’s inner organizational life from government oversight. For centuries, the Roman Catholic church—and its state church descendents in Protestant countries—vigorously fought off perceived threats to the legal doctrine of “benefit of clergy.” Even in America, clergy were shielded from civil or criminal prosecution in most of the British colonies before the Revolution. But in Missouri on October 15, Jackson County prosecutors indicted Bishop Robert W. Finn of the Kansas City-St. Joseph diocese on a misdemeanor charge, saying that diocesan officials had waited for five months—from December 2010 to May 2011—to tell police that a computer technician had given them a priest’s laptop computer containing scores of pornographic images of little girls. Diocesan officials also failed to report that they had received a five-page letter of complaint from a parochial school principal raising suspicions that the same priest “fit the profile of a child predator” in May 2010. “In 2002, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops promulgated new rules requiring bishops to establish independent review boards within their dioceses,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch editorialized on October 18. “In 2008, as part of a $10 million civil agreement with 47 abuse victims, Bishop Finn agreed to even more stringent reporting regulations. Bishop Finn seems to have ignored all of them in favor of the historic Catholic tradition that within his diocese, the bishop is a law unto himself.” “In 2004, the nation’s bishops promised unqualified cooperation with law enforcement,” echoed a New York Times editorial on October 21. “They instituted zero-tolerance for priests but failed to create a credible process for bringing bishops to account. Missouri officials deserve credit for puncturing the myth that church law and a bishop’s authority somehow take precedence over criminal law—and the safety of children.” In Finn’s home diocese, the Kansas City Star repeatedly called for Finn’s resignation. Indeed, the intensity of news coverage of the arrests in Philadelphia and Kansas City was something of a throwback to earlier days of well-staffed newspapers. The Philadelphia Inquirer, the Star, and even the New York Times each mobilized many reporters, including veteran religion reporters (an almost extinct species) to cover the stories. The Finn case followed the February arrest of Msgr. William Lynn, a senior assistant to Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua of Philadelphia from 1992 to 2004, on two felony charges of child endangerment. Prosecutors charged that Lynn, the archdiocesan secretary of the Office of the Clergy charged with investigating claims of clerical misconduct, had failed to take action on complaints lodged against Philadelphia priests and therefore had put thousands of children at risk. The charges arose directly from the case of a 10-year-old North Philadelphia altar boy who allegedly was serially raped by two priests and a parochial school teacher in 1996. One of the priests had previous accusations filed against him in the 1970s and 1980s and had previously been placed in an inpatient sex offender program, the Philadelphia Daily News reported on February 11, 2011. The News said that the Rev. Edward Avery was “released with the recommendation that he be monitored and not be placed around children, according to the grand jury.” While secretary of the clergy, Lynn reportedly “ignored complaints that the after-care team never met, and Bevilacqua assigned Avery to St. Jerome’s, the grand jury found.” Lynn and Bevilacqua were bitterly criticized for their handling of misconduct charges in a 2005 Philadelphia grand jury report that documented widespread clerical misconduct in Philadelphia, but they were not indicted. That report, issued by District Attorney Lynn Abraham after a two-year investigation, complained that while church officials routinely investigated claims of clerical misconduct, they failed to act decisively against more than 60 priests who had been credibly charged. One priest had been reassigned 17 times after complaints, the report charged. But statutes of limitation had long expired on the cases examined in the first report. On February 10, 2011, the current District Attorney, Seth Williams, issued a second grand jury report, charging Lynn with child endangerment, and three priests and a teacher with sex crimes. The criminal charges arose from a criminal complaint in 2009 by the then-22 year-old former altar boy against the priests—one of whom, Avery, had already been defrocked in 2006 on unrelated sexual abuse charges. Further, the second grand jury report stated that at least 37 “priests accused of molestation and other inappropriate behavior toward children have been allowed to remain in active ministry,” David O’Reilly and Nancy Phillips of the Philadelphia Inquirer reported on February 13. “These are simply not the actions of an institution that is serious about ending sexual abuse of its children,” the report said. “There is no other conclusion.” Cardinal Justin Rigali responded quickly. “I assure all the faithful that there are no archdiocesan priests in ministry today who have an admitted or established allegation of sexual abuse of a minor against them,” he said. Rigali then announced that he had hired an independent outside lawyer, a former prosecutor of sexual abuse cases, to review the archdiocesan files. On March 9, he had announced that her review of the files had led him to suspend 28 of the 31 priests pending further investigations. Twenty-one of the priests were on active service. “I know that for many people, their trust in the church has been shaken,” Cardinal Rigali said in a statement carried in the Inquirer. “I pray that the efforts of the archdiocese to address these cases of concern and to re-evaluate our way of handling allegations will help rebuild that trust in truth and justice.” The news also came as a shock to the national church officials charged with tracking clerical sexual abuse. Teresa M. Kettelcamp, executive director of the Catholic bishops’ Secretariat of Child and Youth Protection, told Laurie Goodstein of the New York Times on March 26 that Philadelphia had just passed its annual audit with “flying colors.” On May 4, the Inquirer’s O’Reilly reported that the chairwoman of the archdiocesan board charged with reviewing sex-abuse cases had “lashed out” at Rigali and the other leaders of the archdiocese, “accusing them of having ‘failed miserably at being open and transparent’ about the misdeeds of their priests.” Ana Maria Cotanzaro, a nurse who chaired the Philadelphia archdiocesan review board for the previous eight years, said the board only learned with the publication of the grand jury report that “most cases have been kept from them.” “The board was under the impression that we were reviewing every abuse allegation received by the archdiocese,” she said. They had been sent allegations against only 10 of the 31 priests the grand jury had described as credibly accused. At the same time, Catanzaro published a piece in Commonweal, the lay Catholic magazine, on her experiences on the Philadelphia and national review boards. “If Philadelphia’s bishops had authentically followed their call to live the gospel, they would have acted differently,” she wrote. Catanzaro said she knew from her experience on the national review board that other dioceses ask their review boards to determine whether an accused priest molested a minor and then “make recommendations about his suitability for ministry.” In Philadelphia, however, the “hierarchy focused more on whether an accused priest had violated church law.” She argued that every credible accusation should be investigated by a review board or civil authorities, and that returning credibly accused priests to supervised ministry rarely works because priests are so difficult to monitor. That last point was amply reinforced in Kansas City. On May 19, Glenn E. Rice of the Kansas City Star reported that “Clay County authorities on Thursday accused a 45-year old priest of taking pornographic pictures of children, in a case that church officials learned about in December but didn’t report to police until last week.” Charged was Rev. Shawn Ratigan, a priest serving St. Patrick’s Church in north Kansas City. Bishop Finn immediately issued a statement that began: “[I]n mid-December 2010 I was told that a personal computer belonging to Fr. Shawn was found to have many images of female children. Most of these images were of children at public or parish events. I was told that there was also some small number of images that were much more disturbing, images of an unclothed child who was not identifiable because her face was not visible.” The Star reported that a computer repairman had found the photos and alerted staff at the parish, who had given the computer to the diocese’s information technology officer. When Ratigan discovered that the diocese had the computer, he attempted suicide. After psychiatric treatment, Ratigan was removed from the parish and assigned as a chaplain at a convent in Independence. The parish was not told about the computer photographs, then or for months afterwards. Finn’s statement said he restricted the priest “from participating in or attending other events if there were children present.” During December, church officials had showed the photos on the computer to legal counsel and called a Kansas City police officer who served on the diocesan review board. The diocesan vicar general, Msgr. Robert Murphy, described one of the photos to the officer over the phone, but did not show him any of the photos. Both the lawyer and the police officer agreed that “while very troubling, the photographs did not constitute pornography.” Finn said that in early March the diocese had returned Ratigan’s computer to his family, although diocesan officials kept a copy of its contents. Then, in late March, the bishop “received some reports that Shawn was violating some of the conditions of his stay. I was told he had attended a St. Patrick’s Day parade and met with friends and families. He also attended a child’s birthday party at the invitation of the child’s parents. I confronted him about these things and told him again that he was not permitted to have any contact with minors.” When Ratigan continued to disregard Finn’s instructions, Murphy called the Kansas City police officer again in early May, and the officer immediately alerted the sex crimes unit. Within a week, Ratigan had been arrested. “I deeply regret that we didn’t ask the police earlier to conduct a full investigation,” Finn said. Neither Finn nor Murphy had referred the case to the diocesan review board either. Standing alone at a meeting with 300 parents at St. Patrick’s on May 20, Finn expressed “deep regret” that the diocese had not called the police in December. “One after another—mother after mother, father after father—lined up to speak directly with Finn,” Joshua McElwee reported in the National Catholic Reporter, the liberal Catholic weekly based in Kansas City that has covered the sexual abuse crisis more thoroughly than any other news organization, on May 27. ”Many were in tears. Others were speaking at the top of their voices, almost without words to express their anger.” “I should have acted differently in this regard and I am sorry,” Finn said. “Don’t trust me. Trust our Lord Jesus Christ, trust his church.” “From the earliest days of the Catholic church abuse scandal, the most disturbing theme has been the church’s efforts to underplay its problem,” the Star complained in a May 21 editorial. “Recent events have created a scenario that further undermines the church’s credibility and moral authority.” The Star’s concern looked understated by the end of the week. On May 27, the National Catholic Reporter reported that Finn and Murphy had known as early as May 2010 that many working at St. Patrick’s were worried about Ratigan’s relations with parish children. The same day, the Star also reported that Julie Hess, principal of St. Patrick’s School, had hand-delivered a letter on May 19, 2010 to Murphy that stated she was trying “to fulfill my responsibilities as school principal in relaying a growing body of parent and teacher concerns regarding Pastor Shawn Ratigan’s perceived inappropriate behavior with children.” The letter listed a string of reports from parents and teachers about Ratigan’s excessive interest in children, the amount of time he spent at the school, his practice of allowing children to reach into his trouser pockets, and the ways he decorated the rectory with stuffed animals on guest beds and doll-shaped towels in the kitchen. “Father takes hundreds of pictures of the kids, not just at special events but on field trips and in their everyday activities,” Hess wrote. “A few parents have mentioned that they think this is strange and wonder what he does with all the pictures.” Hess said that she and others at the school who had received diocesan training on child safety worried that Ratigan “fit the profile of a child predator.” Finn’s spokesperson, Rebecca Summers, told the National Catholic Reporter, that—even though they knew about Hess’s letter—Murphy and Finn had not reported Ratigan to the diocesan review board in December because the church guidelines called for a review board “only when you have a specific allegation of abuse.” After the revelation, Finn called a press conference at which he “acknowledged his failure to properly respond to warnings about a priest now accused of possessing child pornography,” Glenn Rice and Judy Thomas of the Star reported in a story headlined “Bishop Says He Failed in Ratigan Case.” “‘I must also acknowledge my own failings,’ said a deflated Bishop Robert Finn as he read from a brief statement during a hastily called news conference,” the Star reported. ‘As Bishop, I owe it to people to say things must change.’” Finn said that after receiving the Hess letter, Murphy had given him a brief oral summary and had reviewed the complaints, point by point, with Ratigan, directing him to change his behavior. “Hindsight makes it clear that I should have requested from Monsignor Murphy an actual copy of the report,” he said. Finn’s response created waves of ballistic rage, not least among activists in the Survivor’s Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP). “Bishops are smart, well-educated men who have tons of resources, lawyers, and public relations professionals,” Mike Hunter, SNAP’s Kansas City president, said in a public statement on June 2. “They know what they’re doing. Finn can’t claim this was a ‘mistake.’ It wasn’t. It was a series of deliberate actions over more than a year to hide potential crimes from the people who needed and deserved to know about those crimes: police, prosecutors, parishioners, and the public.” As in Philadelphia, Finn was obliged to bring outsiders in. In June, he produced a five-point plan and relieved Murphy of his responsibilities to investigate charges of misconduct, hiring an external ombudsman to receive and move forward all allegations of clerical misconduct. He also asked the diocesan review board to expand its role and hired former U.S. District Attorney Todd Graves to investigate the diocese handling of the Ratigan affair and all of its misconduct inquiries. On August 31, Graves issued a 190-page report. Its “key finding was that Diocesan leaders failed to follow their own policies and procedures for responding to reports of misconduct in the Ratigan” case and in another case involving Rev. Michael Tierney. “In both cases, the Diocesan Vicar General, Msgr. Robert Murphy, waited too long to advise the Independent Review Board (“IRB”). In Fr. Tierney’s case, the failure to notify the IRB did not seriously undermine the integrity of the investigation or, in the Firm’s judgment, place minors in danger. The flaws relating to Fr. Ratigan were more serious because neither Msgr. Murphy, nor Bishop Finn, nor others with knowledge brought the matter to the full IRB until after the arrest. Absent IRB guidance, Msgr. Murphy conducted a limited and improperly conceived investigation that focused on whether a specific image on Fr. Ratigan’s laptop, which held hundreds of troubling images, met the definition of “child pornography.” “Rather than referring the matter to the IRB for a more searching review, Msgr. Murphy allowed two technical answers to his limited questions to satisfy the Diocese’s duty of diligent inquiry. Relying on these responses, he failed to timely turn over the laptop to the police. “Although Bishop Finn was unaware of some important facts learned by Msgr. Murphy or that the police had never actually seen the pictures, the Bishop erred in trusting Fr. Ratigan to abide by restrictions the Bishop had placed on his interaction with children after the discovery of the laptop and Fr. Ratigan’s attempted suicide.” Finn’s indictment on a misdemeanor charge followed on October 14. “Bishop Finn denies any criminal wrong-doing and has co-operated at all stages with law enforcement, the grand jury, the prosecutor’s office, and the Graves Commission,” Finn’s attorney said in a public statement. “We will continue our efforts to resolve this matter.” Reporters then took to assessing whether criminal charges against high church officials in Philadelphia and Kansas City were likely to encourage more prosecutors to take action. Writing from Rome, the National Catholic Reporter’s top correspondent John L. Allen thought they might, noting that in recent years a French bishop and two Italian cardinals have also faced prosecution. “Not long ago, Catholic bishops in Europe and North America enjoyed considerable deference from police, prosecutors, judges, and grand juries—sufficient leeway, at least, to make criminal sanctions an unrealistic prospect. Those days, however, seem to be coming to an end.” Other were less sure. David Clohessy of SNAP told Mitchell Landsberg of the Los Angeles Times on October 15 that Kansas City might well be an outlier. “What makes Kansas City different than cover up cases elsewhere is that the wrongdoing is so well documented and so egregious, and actually had lead to real harm to real kids. “In other words, there are little girls in Kansas City whose naked images have been taken by a priest months after suspicions about him should have been reported to the police.” Voices were also raised to defend Finn in the wake of the arrest. Missouri attorney Michael Quinlan took to the Catholic EWTN website, arguing that under Missouri law there was no clear victim in the case and that Finn indeed sent Ratigan for a psychological assessment that concluded that he was not a pedophile. On October 21, William Donahue of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights announced that the League would stand by Finn “without reservation.” A series of press releases and media events followed beginning on October 31 with an attack on the Star for rejecting a League advertisement defending Finn and criticizing SNAP. “We know what’s going on,” Donahue wrote in one of his blog-like press releases. “The Kansas City Star has long been in bed with SNAP, just as SNAP is in bed with attorneys like (Rebecca) Randles and her mentor, Jeffrey Anderson. All are decidedly anti-Catholic. To wit: on September 25, the Star ran a 2223-word front-page Sunday news story on SNAP. To say it was a puff piece would be an understatement.” The Donahue offensive continued through early December, even though Finn himself had decided to engage in more decisive damage control. On November 16, the Star, the New York Times, and other news organizations reported that Finn had reached an agreement with the prosecutor in Clay County, Missouri, to meet every month to report personally on all allegations of misconduct, in order to avoid a second round of criminal charges. (The first criminal charge was made in Jackson County, where St. Patrick’s Church is located. Diocesan headquarters is in neighboring Clay County.) “The agreement leaves the bishop open to prosecution for misdemeanor charges for five years, if he does not continue to meet with prosecutors and report all episodes,” reported A.G. Sulzberger and Laurie Goodstein of the New York Times, “But victim’s advocates criticized the deal as cozy and ineffectual, compared to previous agreements between bishops and prosecutors.” The Times said that Catholic bishops and dioceses in Cincinnati, Manchester, New Hampshire, Phoenix, Santa Rosa, California and Boston have made similar agreements in recent years. In New Hampshire, the deal called for annual inspections of the diocesan records by the state attorney general, with public release of the results. If prosecutors in Missouri were inclined to reach accommodations with the Catholic church, the same cannot be said in Philadelphia, where a brawl between prosecutors and archdiocesan lawyers rolled on through the fall and winter. This included a series of dramatic and explosive pre-trial hearings for Lynn and at least two of the priests charged. A central issue was whether retired Cardinal Bevilacqua, suffering from dementia and cancer at 88, could or should testify at the trial. On January 31, one day after a judge ruled him competent to stand trial, he died. A measure of the paranoia generated by the legal conflict was that on February 12, the district attorney of suburban Montgomery County asked the county coroner to exhume the cardinal’s body and perform an autopsy to ensure that he succumbed to natural causes. Over the summer, meanwhile, Archbishop Rigali had retired and been replaced by Charles Chaput, formerly archbishop of Denver. During the fall, Chaput replaced the archdiocese’s longtime lawyers with a new firm. How he stood on the Lynn case became a matter of intense scrutiny. On October 5, the Inquirer’s John P. Martin reported that Chaput had attended and spoken at a dinner for hundreds of Philadelphia priests in suburban Montgomery County soon after his arrival in Philadelphia. An unnamed priest who attended the dinner told Martin that the new archbishop “singled Lynn out in the crowd and noted how difficult the ordeal had been for him.” Many of the priests attending then gave Lynn a standing ovation. Martin then repeated a remark that Chaput had made just before his September installation: “It’s really important to me, and I think to all of us, that he be treated fairly and that he not be a scapegoat.” The pre-trial hearings were bruising, with prosecutors successfully pushing to be allowed to refer to the archdiocese’s handling of many misconduct cases at the Lynn trial and defense lawyers at one point asking that Common Pleas Court Judge M. Teresa Sarmina remove herself from the trial. That request came on February 9, after Sarmina refused to let them ask potential jurors: “Do you believe child sexual abuse is a widespread problem in the Catholic Church?” In disallowing the question, Sarmina said that “anyone who doubted there was a ‘widespread’ child abuse problem in the Catholic Church is living on another planet,” Martin reported. That dustup followed an eruption of rage from William Donahue on January 31 over another Martin story, which recounted Assistant District Attorney’s Mark Cipolletti’s statement that the archdiocese “was supplying him with an endless amount of victims.” Prosecutors had explained their charges against Lynn by saying that Lynn had “recommended two priests, James J. Brennan and Edward Avery, for parish appointments despite knowing or suspecting they would abuse children.” Both priests already had reports of separate incidents of molesting a boy in their files. Lynn’s attorney, Thomas Bergstrom, called Cipolletti’s remark’s “nutty,” saying that six of the seven accusations against Avery were made after Lynn had left his assignment as secretary of the clergy, yet Cipolletti kept hammering away. Donahue moved it up a notch, calling him malicious: “Just think about what he is saying. We are to believe that ‘the archdiocese was supplying [Avery] with an endless amount of victims’ [my italic]. This boggles the mind. Was the Archdiocese of Philadelphia operating a human conveyor belt—lining the boys up single file before feeding them to predators? Or did archdiocesan officials follow the advice of therapists and allow for treated abusers to return to ministry, just the way every other institution, religious and secular, did up until recently? Prosecutors and defense lawyers went at it again in late February, fighting over whether the discovery of a 1994 memo in which Bevilacqua ordered Lynn to shred a previous memo that stated that 35 priests serving in Philadelphia had allegations of abuse in their personnel files. A copy of the memo, apparently preserved in a locked safe, was discovered in 2006 but not turned over to prosecutors until February, just after Bevilacqua’s death. Defense attorneys argued that the order to shred the memo “proved that Bevilacqua had played an active role in covering up clergy sex-abuse, and that he lied to a grand jury when he said he deferred to Lynn’s recommendations on how to handle such complaints,” the Inquirer reported on February 27. “They asked Sarmina to dismiss the charges, claiming that had the grand jury known of the perjury, they might not have recommended charges against Lynn. Prosecutors, the Inquirer reported, countered that the memo was “a smoking gun for the prosecution case against Lynn. Meanwhile, Sarmina ordered the archdiocese to produce all records of Lynn’s dealings with lawyers by the beginning of the trial. To say the least, no deal with prosecutors seemed in the offing. Meanwhile, far away in Rome, some rumblings were reported as the Vatican prepared new instructions for the world’s bishops about how to handle reports of sexual abuse by clergy. Cardinal William Levada, former archbishop of San Francisco and prefect of the powerful Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, told reporters on February 6 that bishops have an obligation to “co-operate” with local law enforcement. But he stopped short of recommending that the new rules for bishops mandate the reporting of all abuse allegations to police. |