|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links:

From the Editor: |

Sally Gets

Religion

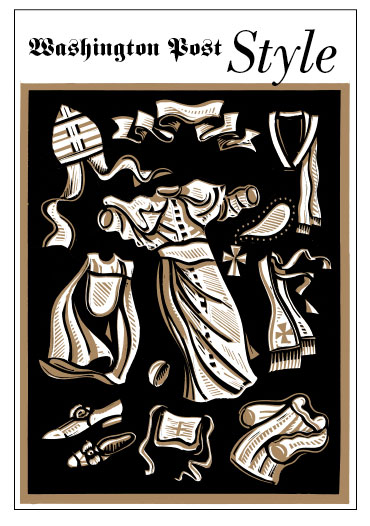

So it isn’t surprising that the newspaper assigned squads of reporters, photographers, and editors to cover the story. Competitors did that too. And plenty of others generated a comparable avalanche of news articles, columns, editorials, blogs, slide shows, film clips, websites, on-line discussion groups, and podcasts about the trip. What set the Post’s coverage apart was a wised-up tone about religion rarely encountered in American journalism since James Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald made a practice of thumbing its nose at priests and prophets in the middle of the 19th century. This breezy attitude has been evident in the Post’s recent coverage of many religion stories and shapes the newspaper’s ambitious on-line “On Faith” section—a massive “conversation on religion” that represents the newspaper world’s most vigorous recent effort to engage religion to combat nearly apocalyptic declines in advertising revenue, readership, and staff morale. The clearest example from the papal visit came in an April 17 set-up story by religion reporter Michelle Boorstein that belied the gravitas of its headline: “Vintage Vestments: The Philosophical Threads Woven in Papal Garments.” On the morning of the pope’s first American mass, Boorstein began, “With all the pundits analyzing Pope Benedict XVI’s views of U.S. foreign policy and the woes of the Catholic Church, we know there are those of you out there with a simple plea: Can someone please tell me when popes started wearing lace and ermine collars?” “A long time ago, that’s when,” Boorstein answered her own question. “And that’s the point.” She proceeded to frame her thumb-sucker as follows: “This may go over the head of the typical viewer flipping through the channels today and watching Benedict celebrate Mass at Nationals Park. But for those concerned about the direction of the Roman Catholic Church, it’s stuff to obsess over. Does it mean that Benedict wants to take the church back into the past, and if so, in what ways? Or does it simply mean this cultured, piano-playing, German theologian has an appreciation for the drama and theater of religion.” To be sure, a few other American journalists also grasped the possibility of divining Benedict’s intentions by scrutinizing his vestment choices. Los Angeles Times editorial writer Michael McGough published a column on April 8 on the symbolic politics of vestments, writing learnedly about the simpler, “neo-Gothic” style of vestments favored by Vatican II types and the baroque “Roman” style that Benedict seems to be resurrecting. Freelance pundit David Gibson chipped in with a similar piece for the Religion News Service, noting that many Catholic liberals fear that “this old-fashioned ‘character’ also comes with an old-style authoritarianism.” But almost no one else adopted Boorstein’s snickering tone, or her insinuations. For those in the know, there has always been a Catholic insider discourse about the homoeroticism of the church’s lavish liturgical culture and the men who love it. A generation ago, hierarchs like Cardinal Francis Spellman of New York and Bishop Fulton Sheen were widely if quietly mocked as men who queened around in especially florid lace-trimmed vestments and tailored cassocks. Boorstein gleaned this specialist’s knowledge by means of a wildly popular blog, “Whispers from the Loggia,” identified by her as “a must-read for hard-core Catholics who want to know every piece of gossip about the church and which bishop is getting transferred where.” Written by 20-something University of Pennsylvania graduate Rocco Palmo, “Whispers” avidly described what the pope (B16 or Papa Ratzi in Palmo’s arch style) was wearing at every public appearance, and Boorstein closed by noting Palmo’s belief that Benedict’s vestment choices “would be watched by Catholics intrigued by ceremonial beauty. By those who want to ‘understand what is hidden.’” Boorstein herself played peekaboo, scattering insinuating language and juxtapositions throughout but never actually asserting that “what is hidden” is a gay sensibility at the heart of Roman Catholic clerical culture. “Why the pope is wearing fur and lace is a subject of some sensitivity,” she remarked at one point. “You thought the cover of Vogue was influential,” at another. She described the papal bureaucrat who oversees papal liturgical matters as “a tall, elegant man who wears a black cassock with buttons from neck to the floor,” a man who also sniffs to signify his disdain for liberals. She quoted a Roman shopkeeper describing Benedict as a vestment trendsetter, completely unlike his (manly) predecessor, Pope John Paul II. “He would just wear whatever was given to him,” Maria Ardovini said. But never in the long, coy riff did Boorstein make a serious attempt to depict the Vatican as a den of hypocritical homosexuals. Nor did she deliver a judgment about the central question she claimed to pose: Is Benedict winding up to a major crackdown on post-Vatican II liberalism? So the story exemplified a “Stylification” of religion coverage, doing unto religion what the Post’s Style section began to do to politics and political culture in the 1970s. Indeed, it not only ran on the cover of Style but also, tellingly, as the principal story of the day on the Post’s website, complete with a brief video set in Rome and narrated by Boorstein. Was that so horrible? Puncturing pretention, including pontifical pretension, is a legitimate venture for journalists. But did it provide a firm foundation for coverage of a consequential journey by the world’s most important religious leader? Perhaps not so much. Why go on at such length about a single dubious article? One reason is that there’s a case to be made that the Post is emerging as American journalism’s new leader in religion coverage. A Ford Foundation-sponsored study called Religion in the Media: December 2006-October 2007, suggests as much, reporting that as staff is cut ruthlessly as smaller metropolitan newspapers, a handful of national players—specifically the Associated Press, the New York Times, and the Post—are generating a larger share of journalism about religious dimensions of the news. “The top producers of religion-related news…have two or more religion reporters, allowing them to pursue more in-depth coverage and a broader range of issues.” The report, the third in a series conducted for Ford since 2001 by Douglas Gould and Company, argues that stories about religion in American politics and public policy in the press have surged over that time, playing into the Post’s natural strength. Indeed, the Post produced 86 percent more religion stories in 2007 than it had in 2001, compared to increases of 13 percent for the New York Times and 22 percent for the Associated Press. By contrast, the study found drops of 13 percent at the Chicago Tribune, 17 percent at the Boston Globe, 50 percent at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 56 percent at the Dallas Morning News, and 60 percent at the Philadelphia Inquirer—all standouts for quality religion coverage in recent years. (The quantity of religion reporting at the Los Angeles Times was found not to have changed at all.) One of the Post’s strengths is that many of its national and foreign correspondents generate a lot of religion coverage, especially when reporting on politics. In addition, unlike religion reporters at many papers, the Post’s Boorstein, Jacqueline L. Salmon, and (until he moved to the book beat) Alan Cooperman often get to write national stories. But even more than this volume of conventional journalism—including a lot of columns about religion and politics—is the extensive space the Post has begun to allocate to religion on its website. The newspaper divides its online coverage of religion into two parts. The first and most conventional is accessed directly from the bottom half of the Post’s home page under the title “Religion.” Once inside this section, one finds a couple of the day’s national or international religion stories, a set of news briefs, and a notes section that lists all sorts of local and national religion events. Each of these sub-sections is linked to a seemingly infinite archive of other entries. On the upper right side of the homepage is a featured story, often with a large collection of photos or videos. The June 11 story, for example, is a profile by Post Saudi Arabia correspondent Faiza Saleh Ambah of a Kuwaiti writer, entrepreneur, and intellectual who has just published “the first Western-style comic book based on Islamic concepts.” Directly below the story of the day is a box labeled “In Depth” that contains links to another set of offerings, the most interesting of which is opaquely called “Multimedia.” This contains dozens of “photos and panoramas documenting religious events and trends around the world,” although mostly in Metro Washington. In this long directory are often spectacular photo “galleries”—reports on the religious lives and practices of, for example, Ethiopian Muslims in Northwest Washington, Catholic converts celebrating their first Easter, religious practices in a Northern Virginia correctional facility, the religious lives of children worshiping at an Orthodox Christian cathedral on Massachusetts Avenue, the Dalai Lama visiting Washington, Donald Wuerl being installed as the city’s Catholic archbishop, and on and on. Some of the files contain dozens of images or lengthy videos and the cumulation makes a powerful statement about the vitality and variety of religious life in Washington as well as about the city’s links to places, peoples, and cultures all over the world. It’s also a fabulous solution to the old journalistic bugaboo, the religious holiday story. These are very skillful, often moving pieces of journalism. And then there is On Faith, which is accessed from the opinions tab at the top of the paper’s home page. This section, a joint venture of the Post and its sister publication Newsweek that debuted in November 2006, delivers on its promise to offer opinion with the force and volume of a fire hose. The pitch begins with a claim that religion “is the most pervasive and least understood topic in global life.” On Faith thus “seeks to engage people in a conversation about faith and its implications in a way that sheds light rather than generates heat.” How so? By engaging “a remarkable panel of distinguished figures from the academy, the faith traditions, and journalism.” The ringleaders, who smile warmly on the On Faith banner, are Newsweek managing editor Jon Meacham and Sally Quinn, long-time star of the Post’s style section. The central mechanism of On Faith is the posing of a provocative or at least fruitful question to an immense panel of experts, who then fire away as they choose in unconstrained cyberspace. The expert panel assembled by Meacham and Quinn is little short of astounding. There’s Richard Land of the Southern Baptist Convention and Jewish author Elie Wiesel, New Age spiritual guide Deepak Chopra and former Iranian president Mohammad Khatani. Also a remarkably, vastly disproportionately large, array of Episcopalians. The motley crew also includes the widest array of academic voices that I’ve ever seen engaged in a single religious project, extending across the country from Princeton’s Elaine Pagels to John Mark Reynolds of Biola University (the former Bible Institute of Los Angeles). The scholars I know best (the American religion crowd) are first rate: not only the once omnipresent Martin Marty of the University of Chicago but also Steve Prothero of Boston University, Kathleen Flake of Vanderbilt, Randall Balmer of Barnard College, and Jonathan Sarna of Brandeis. There is, to paraphrase that wise observer of American journalism A.J. Liebling, a lot of agglutinated sapience here, but it’s used in a strange way. Most of the panel members represent fairly fixed ideas or groups with well established positions, and they respond pretty much the way you’d expect to all the questions posed, be they Starhawk the neo-pagan, the head of the American branch of Opus Dei, or the president of the Southern Baptist Theological School in Louisville. Sometime even predictable comments are highly entertaining, as when Tufts University cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett unloaded on the question for the week of June 9: “Do you believe that faith can affect your health or is that a lot of new age nonsense?” “Of course faith can affect your health, as various studies have shown,” wrote Dennett. So can faith in new age nonsense. So can faith in the Yankees or the Red Sox. People cling to life to learn the outcome of the World Series, after all. The larger problem with this week’s ON FAITH question is that it is being asked at all. This question should not be seen as a matter of personal conviction or opinion at all. People’s hunches, anecdotal recollections, or personal convictions are of no more weight here than they would be about the causes of global warming.” And so it went through 18 “expert” responses, among them Dennett’s fellow secularist Susan Jacoby, several rabbis and liberal Protestant thinkers, and evangelical man-about-town Chuck Colson. Two things are worth noting about this approach. First, it’s odd to empanel such an array of characters as omnibus experts, as if they all had worthwhile opinions about every conceivable religion question that might come up.* At the heart of old-school journalism is the conviction that newspapers are obliged to find and quote genuine experts who have real knowledge of the matter at hand. That seems to have gone by the wayside on-line, where opinion is all. Second, On Faith is not a conversation. A lot of programmatic statements are set down, but there’s no back and forth. Everyone gets a free shot. That hardly matters if the question of the week prompts singer Melissa Etheridge and actress Rita Wilson to expatiate upon their family Easter customs. (Etheridge is a post-Methodist, spiritually conscious person who “believes in the Easter bunny.” Wilson is pretty much a party-line Greek Orthodox believer.) But On Faith has also asked about how bad it is when presidents lie, which unleashed Jimmy Carter to wax lengthily on how very bad it is, and how of course he never did. Attached to the central On Faith blog are many peripheral blogs. A cluster of them emanate from Georgetown University, across town from the Post’s newsroom. These include Jesuit Thomas Reese and theologian Chester Gillis writing mostly about matters Catholic, John Esposito and Hadia Mubarak on Islam and world affairs, and Katherine Marshall on faith and social justice. The most prolific of the Georgetown crowd is Jewish studies professor Jacques Berlinerblau, who blogs away on religion and the 2008 campaign. Another frequent site blogger is the journalist Claire Hoffman, Mistress of Stylification. Charged with commenting on “the actions that people, groups and even nations take in the name of religion,” she assumes the posture that seems to undergird the entire On Faith project. “I will draw insight and inspiration from both experts and people I know who will serve as a regular cast of characters for this feature,” she explains. “From religious scholars to my ten-year old friend Jack who’s wrestling with ideas of the infinite, I want these people to give you their sense of what it means to live under God. “And who am I to do this? I grew up in a fringe religious movement in the Midwest. I started practicing Transcendental Meditation when I was three years old, and my religious background is a swampy-yet-exciting mix of Hinduism, Buddhism, Catholicism, Protestantism and like eight other world views. All of that has left me absolutely convinced that there is no answer. But nothing makes me happier than thinking about how our beliefs about God (or no God) transform and define our lives.” This is the On Faith sensibility: eclectic, non-dogmatic, concerned about extremism, but tolerant. It arises from the surprised and somewhat grudging realization that religion plays so big a role in the world that those of us who have been ignoring it need to bone up. It also arises, presumably, from the minds of Jon Meacham and Sally Quinn. Meacham is in fact heard from very rarely on the site, but he describes himself as a sacramental Christian, an Episcopalian whose mind wanders during church services but who takes Christian life seriously. Hence, maybe, the big platform accorded to Episcopal worthies. Sally Quinn’s voice is much more in evidence. For the past few months, she’s moved into video interviews with the likes of Richard Gere, Desmond Tutu, Karen Armstrong, Ashley Judd, and the aforementioned Chopra. Her omnivorous curiosity is to be appreciated, but her insights often do not penetrate very far. By her own account in a first-anniversary posting last November 14, On Faith developed out of an exchange between her and Meacham in which she declared herself to be an atheist: “He said I should not define myself negatively, for one thing, and that if I was really serious about not believing in God that I should at least have some knowledge about what it was I didn’t believe in. At that point I was completely illiterate on the subject, having been disdainful and contemptuous of religion all of my life. But I took what he said to heart and began to read some of the books he suggested. “All I can say is that I was shocked and embarrassed at how little I knew, and ultimately ashamed of myself for proclaiming myself an atheist when I really didn’t know what I was talking about. I also began to realize that so many people in this world who call themselves religious were just like me. They not only knew nothing or little about their own faith but were just as closed minded and hostile to other religions as I was to all religion.” Being Sally Quinn, privileged Washington bigwig, she decided she would “take a trip around the world to study the Great Faiths. It was a private tour and we started in Rome. From there we went to Jerusalem in Israel and Bethlehem in Palestine; Kyoto, Japan; Chengdu, China; Lhasa, Tibet; Varanasi, New Delhi and Amritsar in India; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; Cairo, Egypt; Armenia; and Istanbul, Turkey. “When I told my friend, ‘On Faith’ panelist and religion scholar Elaine Pagels, about the trip, she asked how long I had spent. ‘Three weeks,’ I replied. ‘But,’ she said in astonishment, ‘you can’t do that trip in less than three years!’” It’s a novelty to have a massive “religion” section launched by so enthusiastic a journalistic entrepreneur. Is it intrinsically bad? The skeptical, uninformed, curious, suspicious, irreverent Quinn viewpoint is widely shared. And evidently there are many readers who appreciate the bouncing around from opinion to opinion, with the editorial function reduced to asking a question and then getting out of the way. There’s something for everyone. But it is troubling that in a world where journalism is experiencing a deep crisis of legitimacy, the Washington Post has launched this vast venture and endowed it with such a puny dose of journalistic ethos. There are On Faith panelists who act like journalists: Gustav Niebuhr, late of the New York Times (and Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Wall Street Journal and Washington Post) and now of Syracuse University; and Lisa Miller and Christopher Dickey of Newsweek, to name three. But even they are not bringing news to the table. Where are the neutral, well-informed voices who rigorously report the news or comment upon it in a reasonably dispassionate (if not necessarily unopinionated) way? Will the on-line media be little more than a vast op-ed-cum-letters-to-the-editor venture, or will there be real, righteous religion reporting? There are a few on-line efforts that do, to some extent, serve as exercises in journalism, such as “The Revealer,” a page or two on the omnibus religion site Beliefnet, and the religion blogs of the Dallas Morning News and the Journal News of New York’s lower Hudson Valley—where news is reported and where journalists comment as journalists on it. At the very least, it would be nice if On Faith were connected more directly to the main product, the main sensibility. The Post’s straight religion coverage is still solid, even though it sometimes yields to the gravitational pull of the blogosphere. If all the investment in new platforms and new approaches to keeping newspapers afloat don’t manage to keep that journalistic voice alive, there won’t be any baby left, only bath water. *As Marc Stern makes clear in his article in this issue, there are times when it becomes clear that one of On Faith’s experts really doesn’t know anything about the subject of the week. |