|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links:

From the Editor: God’s Own Party |

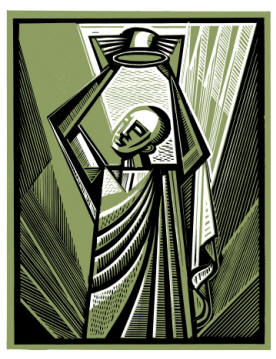

Turning Over the Bowl in Burma

In late August,

a series of widespread and spontaneous protests erupted in response to an

unannounced removal of fuel subsidies by Burma’s ruling military regime. But

prospects for a large anti-regime movement led by pro-democracy activists

soon seemed to fizzle. As the AP reported on August 26, “A week of protests

over fuel price hikes present no immediate threat to Burma’s military rulers

because very few people joined the demonstrations and the key organisers

were swiftly detained, analysts said Sunday.” The monks’ efforts at persuasion were met with a brutal crackdown by police, soldiers, and plain-clothed thugs. This treatment of the most revered members of society shocked and horrified the public and led to an escalation of the protests. In the third week of September, some 20,000 monks walked through the streets of Yangon with their alms bowls overturned. A hundred thousand people marched behind them. At the height of the protests, I was contacted by Seth Mydans, the Southeast Asia correspondent for the New York Times. For 20 years, I have studied the relationship between religion and politics in Burma. Mydans said he was preparing a Week in Review article about “militant monks,” and he wanted some quotes from me on the subject. “Well,” I said, “you’ve got it all wrong.” I told Mydans that if he did write up the protest as a story of militant monks, he would be endangering the movement and putting the monks at risk. That was because “militancy” contradicts Burmese society’s dominant view of the role monks can take vis-à-vis worldly society. It would also have been inaccurate reporting. The protests were almost uniformly peaceable. After listening to me and interviewing one or two other experts on the subject, Mydans wrote an article that, I believe, accurately conveyed the character of the monks’ protest. It began: “As they marched through the streets of Burma’s cities last week leading the biggest antigovernment protests in two decades, some barefoot monks held their begging bowls before them. But instead of asking for their daily donations of food, they held the bowls upside down, the black lacquer surfaces reflecting the light. “It was a shocking image in the devoutly Buddhist nation. The monks were refusing to receive alms from the military rulers and their families—effectively excommunicating them from the religion that is at the core of Burmese culture. “That gesture is a key to understanding the power of the rebellion that shook Myanmar last week.” In 1997, when the New York Times immediately went along with the regime’s renaming of Burma as Myanmar, the country’s leaders gloated that their legitimacy had been recognized by the international media. Speaking with Mydans, I had worried that if the Times described the monks as militant, it would make it easier for the regime to identify the protesters as “bogus monks,” who could then be forcibly disrobed and punished. Of course, the regime was intent on this course of action in any case. But the monks were in all likelihood able to conduct their marches through much of September without military suppression because they were widely recognized as acting in accordance with their prerogative as the religious authorities of the land. This form of public moralizing without direct engagement in politics must be understood if one is to make sense of the monks’ involvement in the protests. The monks’ “anti-political” engagement derives from two states of affairs in Burma, one relatively recent and the other ancient. First, widespread antipathy toward the military regime has existed since the violent suppression of student protests in August 1988. A landslide election in favor of National Democratic League leader and Nobel Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi in 1990 was disregarded by the regime, and Ms. Suu Kyi has spent most of the intervening years under house arrest. Since then, there have been no formal power-sharing institutions apart from the military, and political activism of any kind is quickly found out by spies and suppressed. It has been illegal for more than five people to gather in one place. Under the circumstances, those who wish to stage political resistance have no choice but to do so by veiled means and away from the ubiquitous surveillance of the regime. It would take a book to give a proper account of this resistance. The forms of it that I have observed in Burma over the past two decades have all mirrored the structure of the present uprising, on a much smaller scale. All have taken place in or through the religious sphere. Burmese people wear amulets of monks who are famous both for their spirituality and their refusal to be co-opted by the regime. They make pilgrimages to such monks, spread rumors of supernatural retribution against the regime (such as the rumor that their sacred white elephant had committed suicide), and donate property to monks and monasteries to avoid nationalization (since the government does not touch or tax various categories of sacred property). In these and other ways do they surreptitiously but unmistakably escape from and protest the controlling activities of the regime. It is equally important to recognize that religious anti-politics is also rooted in the Vinaya, or monastic code of conduct, which seeks to enforce the vows of renunciation taken by monks by explicitly prohibiting them from engaging in worldly affairs. Contravention of the Vinaya is grounds for disrobing, traditionally a voluntary act taken by the monk himself in cognizance of his violation. Marching in a political rally would certainly qualify as a violation of the prohibition. One exception is allowed, however. This can occur when some person or persons are seen as acting in ways that threaten the Sasana—the teachings of the Buddha, or, for our purposes, the Buddhist religion. In such a case case, the Sangha (order of monks) is permitted to issue what is regarded as the ultimate moral rebuke: refusing to accept donations. The act is known in the Pali language as “patam nikkujjana kamma”—turning over the bowl. To refuse to accept someone’s donation is to deny that person the opportunity to earn merit. Merit is a moral condition that produces real world power and felicitous circumstances in one’s future life. When the Sangha formally announced on September 18 that it was denying the military the opportunity to earn such merit, it was doing something much more important than intimating the public’s desire for regime change to democratic rule. By refusing to function as the “merit fields” in which the military can sow their future prosperity, the monks effectively removed the spiritual condition sustaining the regime’s power. That was the meaning of their parading with upturned bowls. The monks’ boycott extended to all donations from the military regime’s leaders, their families and close associates. To combat this, the military at one point went so far as to bar regular citizens from offering to the monks, in order to force them to accept military donations. Yet even in the face of this, many monasteries refused the donations, and rice sacks lay unopened on the monastery grounds. Monks who were taken to prison also refused to accept alms from the military, many of them going on hunger strikes. The moral force of such refusal was evident in 1990, when there was a smaller movement of turning over the bowl. Then, military wives refused to cook for their husbands until they apologized to the Sangha, since their own merit fields were jeopardized. Indeed, there have been instances of this kind of protest throughout Burmese history, and in many cases the results have been momentous. What is involved is the classical moral dialectic between Sangha and State. The Sangha has the role of admonishing rulers to conform to the law of dhamma, the moral causal law of justice. The rulers for their part see to it that members of the Sangha do not stray from their own code of conduct. Thus, on September 21, the Pokokku monks issued a statement (reported from Bangkok by the Inter Press Service) that declared: “The violent, mean, cruel, ruthless, pitiless kings—the great thieves who live by stealing from the national treasury—have killed a monk at Pakokku, and also arrested reverend clergymen by trussing them up with rope. They beat and tortured, verbally abused and threatened them. The clergy boycotts the violent, mean, cruel, ruthless, pitiless kings….The clergy hereby also refuses donations and preaching.” The statement was a significant rebuke, but remained highly moral and anti-political. The language of kingship and refusal of donations remained within the traditional bounds available to the Sangha in desperate times. But even as the monks undertook their anti-political rebuke of the regime, so the regime was bound to reply according to the same language—by interpreting the monks’ actions as being “against the religion” by virtue of the fact that, according to the regime, they had stepped outside of their role as renunciates. On October 6, the junta’s propaganda newspaper, the New Light of Myanmar, stated that the monks’ actions were “in total disregard of the Sasana and the Buddha’s teachings, and they attempted to tarnish the image of Buddha’s Sasana and sow discord between the government and the people. As a result, the Sasana as well as the country was affected.” The New Light reported that, in line with the Vinaya’s proscription of political activism among the clergy, the military had announced that “monks and nuns taken in the raids were defrocked before interrogation and those found to not have participated in the demonstrations were reordained and sent back to their monasteries.” According to the newspaper, “The handling of the situation during the violent protests and measures taken by officials for purification of the Sasana amounts to serving the interest of the Sasana. Officials are to make continued efforts for perpetuation, purification and propagation of the Sasana.” In fact, some monks—younger ones in particular—did made gestures and statements in the language of the democracy movement. It was this more expressly political position that the Western media has emphasized. On October 24, for example, Agence France-Presse reported, “Myanmar has been in the world spotlight since pro-democracy protests spearheaded by the country’s revered Buddhist monks were violently put down by the regime last month.” And on December 7, AP spoke of “[m]ounting pro-democracy protests led by Buddhist monks.” Only one journalist, Dinah Gardner, captured the anti-politics story, in a November 10 article in Asia Times Online: “The real tragedy was the politicization of the protests. The monks first marched only to plead with the government to do something about the crippling poverty….Matters started to go awry, say observers, when the main opposition, the National League for Democracy (NLD), jumped on board and added their call for democracy. The order to start shooting would never have been given if the demonstrations had not been sabotaged. “‘The monks would be marching and the NLD would run ahead, parting the crowds and directing the monks like traffic,’ remembers one Yangon-based expatriate. ‘At one point they came to a junction and waved the monks towards the right-side route, but the lead monks choose the left path. That was telling.’ “The protests could have gone on for much longer if the monks had been in charge, says another NGO worker. ‘I think it’s really a pity that the protests didn’t just stick with the monks because what would the government have done if the monks peacefully walked on and on and on? It would be very difficult for them to start shooting. They would have had to tolerate it for a longer time and then you would have started this culture of demonstrations.’ “Even activists agree that the bulk of Myanmar’s citizens just want a better life. ‘Most people don’t know much about democracy,’ said a Yangon-based former political prisoner. ‘They just want enough money to feed their family.’” The two protest positions—the anti-political turning over of the bowl and the pro-democracy activism—are, in fact, not easy to disengage. For the media, the challenge of making sense of the Burmese religio-political landscape is hugely complicated by lack of physical access. Even so, the Internet has opened up possibilities for accessing internal reports and interpretations in an entirely new way. Scholars of Burma have themselves relied much more on these sources than on newspapers to keep abreast of the developments on the ground. In addition, the thriving pro-democracy activist movement outside the country, which includes many expatriate Burmese, has contributed much to shaping the understandings on the ground in Burma. Activists have fastened on to the voices of the All Burma Monks’ Alliance, the most explicitly pro-democracy group within the Sangha. As in any political debate, there are bitter divisions outside the country over the question of how to bring about regime change in Burma. These have centered on the question of the usefulness of sanctions and, more fundamentally, the question of the relevance of the notion of democracy itself in a country where exposure to its principles has been rudimentary at best. The most widely understood moral principles of fair and just governance still derive from Buddhist models. The mass protests by monks stemmed specifically from the regime’s refusal to be morally corrected by the Sangha and to amend its behavior in accordance with the monks’ rebuke. The regime’s violent reaction to the monks’ action suggests that there can be no return to status quo ante, and that the ’07 protest therefore represents the beginning of the end for the regime. At this writing, although the events in Burma have stopped being widely reported on, the monks have continued their boycott. The laity are said to be attending, and passing around VCDs of, monks’ lectures that are bold in their discussions about bad kings and about the regime’s planting of bogus monks into the Sangha. The best hope for regime change may continue to lie, as hope for reform always has in Burma, with the Sangha’s moral authority. |