RELIGION IN THE NEWS |

||

|

Table

of Contents Summer 2004

Quick Links:

|

Breaking Boston's Heart

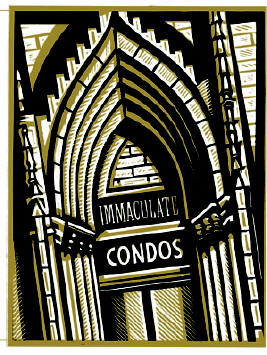

Church bells pealed joyfully all over eastern Massachusetts as Federal Express trucks made their rounds on the morning of Tuesday, May 25. On board were overnight letters from Archbishop Sean P. O’Malley addressed to the 357 parish pastors in the Catholic Archdiocese of Boston. About 80 percent contained the welcome news the recipient’s parish had dodged a bullet, and would not be closed. Many of those pastors responded spontaneously by setting their bells a-ringing. But 70 of the letters contained bad news: Sixty of the parishes would be closed outright within a few months and an additional 10 would be merged to create five new parishes. In those places, a blizzard of local news coverage reported, the pastoral reaction was more often weeping. Within a few weeks the total of closed and consolidated parishes inched above 80. Further, the “realignment” came on top of about 50 parish closings that had taken place since the mid-1980s under O’Malley’s predecessor, Cardinal Bernard Law. The retrenchment—the largest in the history of the American Catholic church—is a stark measure of change in overwhelmingly Catholic New England, where almost 70 percent of those who claim some religious identity say they are Catholic. But even the persistence of numbers like that cannot hide the damage done by decades of population movement to the suburbs, falling Mass attendance, the dramatic aging and shrinkage of the priesthood, and the awesome damage done by the clerical sexual abuse scandal that broke in 2001. Kathy McCabe’s story, headlined “Sadness Grips Closed Churches,” in the May 30 Boston Globe, captured the sense of the occasion. Many letters arrived during the celebration of daily Mass and were read aloud to the small Tuesday congregations. That happened at Our Lady of Lourdes Church in Revere, a working class suburb north of Boston. When the FedEx man arrived, the Rev. Thomas Keyes told the Globe, “I was consecrating the Eucharist.” “Keyes couldn’t leave the altar. The Fed Ex worker left the church. No one was at the rectory to sign for the special delivery from Archbishop Sean P. O’Malley. Keyes looked at Nick Giacobbe, who was seated at the back of the church with his wife Marie. ‘I said, “Nick. Go get the letter from the FedEx man.”’ “‘I met the guy outside,’ recalled Giacobbe, 72. ‘I said to him. “I think I know what you have, and I really don’t want to take it.” I did take it…but I almost didn’t want to come in with it. This is not an easy time for Catholics.’ “Keyes read the letter to 30 parishioners after communion. ‘After careful consideration, and an extensive process and review, I am writing to inform you that I have decided the Our Lady of Lourdes Parish must close,’ O’Malley wrote. The group then wept together about the closing of their 99 year-old parish. A few then went outside to pray the rosary in the parish garden. ‘We had decided we would do that, whatever the decision was,’ said Giacobbe. ‘We wanted strength….We were bawling in our church.’” That same week, Naida Eugenie Snipas discovered that she would be the last woman to be married in St. Peter’s Church, a Lithuanian parish in South Boston. “It’s heartbreaking,” she told Peter Gelzinis of the Boston Herald on May 28. “The thought of losing my church has left me with a big knot in my stomach. I don’t want to be the last wedding held at St. Peter’s. I want my friends and so many others I know to be married here. Someday I want my children to be baptized here….For me, St. Peter’s has always been more than a church. It is the heart of my community, a place where I always felt so at home.” For most journalists, especially reporters for the dozen daily newspapers that circulate inside the boundaries of the Archdiocese of Boston, this was mostly a story about parish closings and their impact on the hyper-local culture of New England. A survey of headlines gives a sense of the basic take: “Heartbreak for South Shore Catholics,” in the Quincy Patriot Ledger; “Church Closings Rip at Parishioners’ Psyches,” in the Lowell Sun; and “Losing More Than Mass, Church Gateway for Immigrants,” in the Globe. No one was surprised that O’Malley, in office just a few months when he announced the consolidation initiative, should decide to close parishes. It was widely acknowledged that population movement to the suburbs had left New England’s aging manufacturing centers with a large number of lightly attended parishes, often with aging and expensive parish plants. “In some older neighborhoods, a one-mile walk can take you past four of five Catholic churches, O’Malley said during a talk on Boston Catholic Television on February 5. “We just can’t sustain that kind of reduplication. Under the best of circumstances it was impractical. In our present situation it is impossible.” But hard to swallow. In Massachusetts, parishes still define neighborhoods and—almost unbelievably in contemporary America—many people in and around Boston still walk to church. “I appreciate people’s attachment to an individual church building. There are so many familiar associations with a particular parish,” O’Malley told a gathering of priests on December 15, when he announced a comprehensive process designed to prune the archdiocese in order to create healthier parishes. “It’s a sad moment, but unfortunately, it’s a very necessary one,” the Associated Press quoted him on December 15. The archbishop had prepared the way for the process of closing parishes by first attempting to wrap up the lingering institutional difficulties associated with the devastating scandal that brought down Cardinal Law. In September, O’Malley agreed to a $90 million dollar settlement of more 500 lawsuits, selling off the large campus where the archbishop’s mansion was located to Boston College for more than $100 million. He then announced that the parish-closing initiative had nothing to do with the financial fallout of the scandal. Michael Paulson, the Globe’s religion reporter found widespread agreement among priests at the December meeting that a large number of closings were unavoidable. “It’s a bit scary because I don’t know what the future holds,” said the Rev. David P. O’Donnell, pastor of St. Colman of Cloyne Church in Brockton. “But I do believe, ultimately, as a result of reconfiguration, the parishes will be stronger.” In the same story, Paulson quoted the Rev. Austin H. Fleming, pastor of Our Lady Help of Christians parish in West Concord: “This very definitely needs to happen. The dwindling number of priests and the demographic changes in the archdiocese have been going on for a long time, but pastors and bishops have been afraid to tackle the issue. But I’m concerned because I don’t know how much substantial input from the grass roots is going to be possible in the timeline he provides.” From December to May, journalists were riveted by the process laid down by O’Malley, who went down in most books as a bold and decisive leader eager to get painful business done quickly. He was willing to spend the political capital earned for his work cleaning up the abuse crisis. “I shall not abdicate my responsibility to make the hard decisions. Since coming to Boston I’ve had to make the hardest decisions of my life,” O’Malley told his priests at the December 15 meeting. In other Catholic dioceses, parish closing debates had extended for years, but O’Malley said that the parishes to be closed would be selected within a few months and terminated by the end of 2004. He then ordered priests and laity in 80 clusters of parishes ranging from three to eight in number to meet among themselves to recommend which parishes should be axed. The immediate result was an explosion of anxious but—atypically—very public discussion about the future of the church. And a parallel explosion of journalism. Between January and March, there were scores of cluster meetings across the region, all covered by teams of competing reporters. The volume of coverage was striking—each of the Globe’s five regional weekly zoned editions carried a major story about the process. The Globe, Herald, Lowell Sun, Patriot Ledger, and a handful of smaller papers all poured their staffs onto the story. The archdiocese also broke with previous practice and released a great deal of information about parish life—a third of parishes were running deficits, and many had much smaller attendance than was the general impression, especially in the older industrial cities. The annual survey of attendance at Mass, conducted each year in October, revealed that one in six Catholics attended Mass in a given week—a figure well below national averages and significantly below pre-scandal trend lines in the Boston archdiocese. Initial reaction to O’Malley’s plan was nervous, but supportive. “State officials hoping to close cherished local institutions like courthouses should look to the Archdiocese of Boston to see a difficult closure process done well,” the Herald editorialized on December 23. Once the cluster meetings began, however, anxieties about the process surfaced. While many laity were happy to be asked to participate in the meetings, Kellyanne Mahoney reported in the February 8 Globe that lay leaders soon grasped the thorny nature of the assignment they had been handed. “[W]hen they ask you to make a recommendation,” Mary Hogan of St. William’s Church in the Dorchester section of Boston said, “people are really being invited to surrender their own or sacrifice somebody else’s parish to save their own.” Among the most agitated were public officials, an overwhelming Catholic group in Massachusetts. Boston Mayor Thomas Menino worried publicly about the impact of impending parochial school closing on public school costs and the disappearance of parish-based social services in poor neighborhoods where Catholic churches are islands of stability. Secretary of the Commonwealth William Galvin told the Globe on December 29 that he “suspected that the archdiocese had already selected the parishes to be closed. ‘It’s hard to think you can have a true process in three months,’ said Galvin. ‘I think there’s a list.’” Others were less diplomatic: “The closure process pits neighbor against neighbor,” Steve Callahan of Norwood complained in a letter to the Globe published on February 15. “Cluster voters are voting subjectively on sacrificial parishes to ensure the survival of their own.” Eventually, metaphors borrowed from reality television cropped up everywhere. “In an unseemly scene that is being repeated throughout the Archdiocese of Boston, parish groups are getting together to basically vote one of their fellow churches off the island,” Globe reporter Bella English wrote in a March 7 column in the weekly “Globe South” section. Indeed, the Globe’s Michael Paulson reported soon afterward that 20 percent of the clusters, especially in suburban areas where churches are often full, had refused to name parishes for closing. That ploy failed because O’Malley instructed regional administrators to name parishes for closing. The clusters eventually named 100 parishes, and archdiocesan administrators named 37 more to a list to be given final scrutiny. Reaction at the parishes placed on the list was uniformly bad, and several priests stepped out of line. “We’re shocked” said the Rev. Lawrence Rondeau, pastor of St. Joseph Church in Salem, who broke into tears in the course of an interview with Paulsen on May 7. “We’re very surprised because the cluster did not vote for us to close. We thought we had a good chance of being spared.” On May 10, John Zaremba of the Patriot Ledger reported that another pastor had denounced the process from the pulpit. “I feel that we and 36 other churches have been betrayed by the archdiocese,” the Rev. John Kelly of St. James Church in Stoughton told parishioners at Sunday Mass. Urging them to write to O’Malley, Kelly said, “We did not have a chance, an opportunity to present a very valid case. I think that is simply unfair.” O’Malley dropped the hammer, as he had promised, on May 25—“Judgment Day,” according to page one of the tabloid Herald. Along with 60 churches to be closed were at least three parish schools. “Please do not interpret reconfiguration as a defeat,” the archbishop’s public statement read. “It is rather a necessary reorganization for us to be positioned for the challenges of the future, so that the church can be present in every area of the archdiocese with the human and material resources we need to carry on the mission that Christ has entrusted to us.” “The closing of 60 of the archdiocese’s 357 parishes is heartbreaking. And indisputably necessary,” the Herald editorialized May 26. “O’Malley has set the archdiocese on a course of healing, financially and spiritually. Accepting these church closings is one of the higher mountains he will ask Boston-area Catholics to climb.” The Brockton Enterprise took a tougher stance in an editorial on May 27 headlined “Church Must Work to Keep Catholics in Fold,” which argued that the sexual abuse scandal had helped create the conditions the forced contraction. The editorial also offered, in unusually lyrical terms, some insight into the way many Catholics feel about their parishes. “It’s hard to estimate the pain felt by the parishioners whose churches will be closed. Their churches are, after all, more than assets on a balance sheet. They are the places where the most profound moments in their lives have been sanctified—at baptisms, weddings and funerals. They are the source of cherished memories—of candles burning bright against the darkness at midnight Mass, of their children dressed in white, receiving their first Holy Communion, of sipping coffee with friends in the parish hall.” Massachusetts journalists covered the story of the Boston “realignment” thoroughly, with a remarkable volume of stories. Virtually no parish was left without its moment in the sun. And much of the coverage revealed a good deal about the deep structure of local life, feelings, rituals, and patterns than is usually the case. But the focus was almost entirely on human interest stories, not on the big picture. Given the high level of investment in covering the story, it is striking that the coverage was so insular, so bound up by the local frame of reference. It seemed as if Massachusetts journalists could barely conceive that the Catholic church might organize itself in any way other than its entrenched local form. Barely any attention was given to parish closings and processes elsewhere in America. If that had been done, at least one major theme might have emerged more clearly. Archbishop O’Malley’s drastic pruning of the archdiocese aimed to preserve a model of parish life in which priests are the center of the community, and priests control its life. In other parts of the country, bishops have either chosen or been obliged by circumstance to redeploy priests while leaving many parishes in the hands of teams of lay leaders, nuns, and deacons. In Massachusetts this option was passed over, virtually without discussion. Few asked whether it was really necessary to close 20 percent of the archdiocese’s parishes at one fell swoop. The church’s public rationale was that falling church attendance and a steep drop in the corps of parish priests required rapid and drastic action—O’Malley said in his February 5 talk that the number of priests in the archdiocese fell 37 percent between 1988 and that action had to be taken before “priests in their 70s become priests in their 80s.” But by the standards of the rest of the country, Boston still has lots of Catholics, lots of parishes, and even lots of priests. Somehow, for all involved, it seemed impossible to visualize a viable Catholic parish where only several hundred attend Mass in a given week. O’Malley quite openly argued that the reconfiguration had to be pursued rapidly to adjust the parishes of the archdiocese to the reduced number of priests available, rather than reconfiguring ministry to staff the parishes. For example, on May 27 the Globe reported the closing of St. Bernard Parish in West Newton, with the planned layoff of seven full-time employees and the reassignment of two priests. The parish was to close despite weekly attendance at Mass of more that 720 and 200 lifecycle (baptism, marriage, funeral) sacraments a year. But professional lay employees were carrying much of the burden of ministry. Ultimately, the O’Malley model is designed to minimize changes in Catholic parochial life by creating fewer, bigger parishes. A Globe editorial on May 27 made the point, but obliquely: “The fatalistic approach of church leaders dating back to last January is driving much of the disappointment. Parishioners in many of the affected churches were eager to discuss ways to save their places of worship, such as lifting the workload of priests so they could serve more than one parish and expanding the role of deacons. But the leadership of the archdiocese limited meaningful lay involvement to just one area—recommendations for closures in their regions.” Indeed, by the end of the summer there was discernible resistance in only a dozen of the 82 parishes slated for closing. For their part, journalists did a poor job explaining the financial structure of Catholic parishes, and especially failed to address why falling church attendance created such a sharp financial crisis in the past few years. Most of the parishes closed had attendance figures far higher than Protestant, Jewish, or Eastern Orthodox congregations in the region that are regarded as stable and healthy. Parishes with weekend attendance of above 800 were closed—four or five times the size of viable mainline Protestant congregations. The key financial fact is that Catholic parishes rely for their support almost entirely on money placed in collection trays during Mass. Most other religious groups do not, relying instead on annual pledges or dues that are collected whether or not members are in church on a given Sunday. This reflects the longstanding reality that the Catholic Church has depended on small contributions from a very large number of people, but also the deep Catholic sense that membership in the church derives from baptism, and not from paying dues. During the summer of 2004, Massachusetts journalists kept busy covering protests, mourning rituals, and the first large wave of closings, planned for early September. They also turned their attention to the question of what the church will do with surplus buildings and how much it expect to realize from sales of buildings. As early as May 27, the Globe’s Steven Kirkjian reported that the entire stock of surplus churches, schools, rectories, convents, and community centers might fetch $400 million on the hot Massachusetts real estate market—most of it coming from developers likely to turn them into condos, condos, and more condos. That’s a lot of money, even for a strapped organization like the Archdiocese of Boston. Couldn’t O’Malley have cashed in fewer chips and saved more parishes? |

|

|

|

||