|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Table of Contents Summer 2006

Quick Links:

From the Editor: Religious Politics, Japanese Style Cult Fighting in Middle Georgia

|

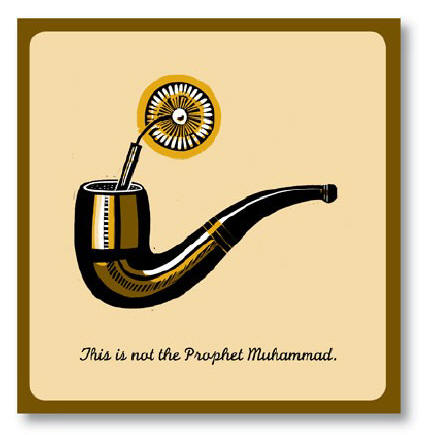

To Print or Not to Print? By the end of January, Danish embassies and consulates were being torched, dozens of people were dying in violent protests, and superheated charges of blasphemy and anti-Muslim bigotry were detonating like thunder around Denmark’s largest daily newspaper, Jyllands-Posten, which had published a dozen cartoons lampooning the Prophet Muhammad on September 30. Suddenly, European news--papers felt the urge to show their readers what all the fuss was about. Without coordination, they began to republish the cartoons as a gesture of solidarity with Jyllands-Posten, and as a bugle call in defense of freedom of speech. On February 1, the Parisian tabloid France-Soir devoted its entire front page to a new cartoon depicting the world’s deities agreeing “we’ve all been caricatured.” The headline: “Yes, we have the right to caricature God.” Inside, all 12 of the Danish cartoons were reprinted. Across town, Le Monde also reprinted one of the Danish cartoons prominently the same day, and on February 2 Libération printed two of the most pointed cartoons. In Italy, meanwhile, Milan’s Corriere della Sera published two cartoons on January 30, and Turin’s La Stampa printed all 12 on February 1. In Spain, El Mundo published the 12 on February 1, followed by El Pais the next day. In Germany, the conservative Berlin daily, Die Welt, printed all 12 on February 1, and the sober weekly, Die Zeit, printed one. And so on through eastern Europe and up across Scandinavia all the way to Greenland, where Sermitsiaq reprinted three of the cartoons on February 2. In the United States, however, there commenced publication not of the cartoons, but rather a remarkable series of stories, editorials, and explanations—in outlets ranging from the New York Times and the CBS Evening News to the Dubuque Telegram Herald and the Victorville (California) Daily Press—about internal newsroom discussions of whether to publish the cartoons. USA Today’s media critic Peter Johnson reported in a column that the “debates” were “intense.” National Public Radio ombudsman Jeffrey A. Dworkin drew a typical picture in a column published on NPR’s website on February 7. He depicted Bill Marimow, a multiple Pulitzer Prize-winner who is NPR’s acting vice president of news, as agonizing over whether to reprint the cartoons. “As you know, Jeff, my thinking about this had changed throughout the day—as I’ve read more about the subject and discussed it with our colleagues,” Marimow said in an e-mail quoted in Dworkin’s piece. A few days later, the Hartford Courant’s reader representative, Karen Hunter, noted that “nothing gets journalists talking like a freedom-of-the-press debate.” “Editors Wrangled Over Printing Cartoons,” ran the headline over her column. These newsroom discussions were evidently Very Serious, but the published results suggest that there can’t have been much actual disagreement. In stark contrast to Europe, only a tiny handful of American news outlets chose to show readers or viewers the cartoons. Even the Associated Press declined to move them on its newswire. Those bucking the trend can be listed in a brief paragraph. The tiny and iconoclastic New York Sun published two cartoons on February 2 to illustrate an Associated Press story. The Austin American-Statesman and Riverside (California) Press-Enterprise each reprinted one of the cartoons as part of a news package on February 3, followed by the Philadelphia Inquirer on February 4 and the Denver Rocky Mountain News on February 7. The Victorville Daily Press brought up the rear on February 8. On the video side, only Fox News Channel showed images of the cartoons and ABC News flashed one briefly on the screen. Anders Gyllenhaal, editor of the Minnesapolis Star-Tribune laid out the most common reasoning for not publishing the cartoons in a brief story written by Eric Black, published on February 7. Gyllenhaal called the cartoons “purposely sacrilegious” and said the Star-Tribune doesn’t publish something offensive “simply to prove we can.” The same day, the New York Times defended its choice not to republish the cartoons by saying, “The easy points to make about the continuing crisis are that (a) people are bound to be offended if their religion is publicly mocked, and (b) the proper response is not to go on a rampage and burn down buildings.” It and most other American newspapers were content to report on the cartoons without showing them because this was “a reasonable choice for news organizations that usually refrain from gratuitous assaults on religious symbols, especially since cartoons are so easy to describe in words.” “There’s a huge difference between freedom of the press and deliberately insulting the religion of another,” Gina Lubrano, the San Diego Union-Tribune’s reader representative led her February 13 opinion piece. Martin Baron, editor of the Boston Globe, told his newspaper’s ombudsman, Richard Chacon, on February 12, that reprinting the cartoons would have been a violation of the newspaper’s standard policy not to “reprint phrases or images that are considered to be grossly offensive to a religious, racial, or ethnic group.” “The right to mock a religion may be absolute, but so is the right to publish most forms of pornography: Neither is appropriate in a serious publication,” the Wall Street Journal editorialized on February 4. “That applies whether the religion is Islam, Christianity or any other, and whether the cartoons are being published for the first time or reprinted elsewhere as acts of solidarity in the face of an implied threat.” It might come as a surprise to many people, but American news organizations don’t do sacrilege, at least not usually. For insiders, the mass decision not to reprint the Danish cartoons was predictable and the contretemps unexpectedly revealed a pervasive, but rarely articulated, norm that shapes how American journalists deal with religion. Cartoonists expressed this norm even more clearly than their editors. “The standard at most major papers is that cartoons don’t ridicule religions as religions,” Dan Wasserman of the Boston Globe told Chacon. “Cartoons often satirize religious institutions and leaders for their actions in the world…but not basic tenets of faith.” Mike Luckovich of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution agreed in a piece published on February 18: “Cartoonists have a lot of a latitude, but criticizing the basis of someone’s religion—their deity or their prophet—I think you can make a point without doing that.” Allowing as how religion “isn’t off limits,” Luckovich said he felt free to criticize religious leaders and had “drawn Jesus in cartoons, but I’ve never done it to defame him.” American cartoonists often deploy religious imagery in the pursuit of their targets. This often irks pious readers, but it works differently from the Danish onslaught on the Prophet, as the small tempest over a Jeff Darcy cartoon in the April 9 Cleveland Plain Dealer illustrated. The cartoon played off of two recent stories: publication of a long lost “Gospel of Judas” and testimony by former presidential aide “Scooter” Libby that it was President Bush who had authorized him to leak the name of CIA agent Valerie Plame to a reporter. Darcy portrayed a tattered “Gospel of Judas” with the legend “It was W’s idea—Scooter” over a portrait of President Bush nailing himself to the cross and saying, “WHOEVER LEAKED OUGHTA BE CRUCIFIED!” In his April 16 column, Plain Dealer ombudsman Ted Diadum granted that the timing of the cartoon—during Christian Holy Week—“left something to be desired,” but noted that the object of the satire was George Bush, not Jesus. “The cartoon didn’t work so well when it came to considering the sensibilities of many of our Christian readers,” Diadum admitted. “But while the cartoon might have made some of us uncomfortable, it was not anti-Christian in tone or intent. Nor was it gratuitous.” By contrast, Flemming Rose, the Jyllands-Posten culture editor who commissioned the Muhammad cartoons, wrote in a February 19 piece for the Washington Post, “I commissioned the cartoons in response to several incidents of self-censorship in Europe caused by widening fears and feelings of intimidation in dealing with issues related to Islam. And I still believe that this is a topic we Europeans must confront, challenging moderate Muslims to speak out.” Rose’s objective—confronting a minority culture to press it to assimilate—is jarring enough to American journalistic ears, but not nearly as much as his explanation for why this was necessary. The string of “alarming incidents” that he pointed to began in September, when his newspaper published an interview with a Danish comedian who said that “he had no problem urinating on the Bible in front of a camera, but he dared not do the same thing with the Koran.” The problem, as Rose viewed it, was that the comedian should have had no hesitation about urinating on the Koran. In Rose’s mind, Jyllands-Posten was rising to defend an aggressive secularism that makes a virtue of attacking religious sensibilities. “We have a tradition of satire when dealing with the royal family, and other public figures,” Rose wrote of Jyllands-Posten. “And that was reflected in the cartoons. The cartoonists treated Islam the same way they treat Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism and other religions. “And by treating Muslims in Denmark as equals they make a point. We are integrating you into the Danish tradition of satire because you are part of our society, not strangers. The cartoons are including, rather than excluding Muslims.” That European franchise expressed in France-Soir’s proclamation, “We have the right to caricature God,” is not one American journalism likes to exercise. Christopher Hitchens, writing in Slate on February 4 was a rare American voice—if a born-and-raised Brit can, in this context, be considered American—for anti-religious secularism: “There is a strong case for saying that the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten and those who have reprinted it out of solidarity, are affirming the right to criticize not merely Islam, but religion in general.” But what of the handful of American publications that reprinted the cartoons? Each presented its own argument, but the common theme articulated by editors was that because the cartoon controversy had become so large, readers had a right to see what was causing the trouble. Since these papers didn’t see themselves as defending the abstract cause of freedom of speech, they tended to run not all dozen cartoons but only one or two—most often the one viewed as most offensive: the prophet in a bomb-shaped turban, complete with scowl and burning fuse. Richard Oppel, editor of the Austin American-Statesman, decided to run a small version of the turban cartoon next to an Associated Press story about why Muslims view depictions of the prophet as so offensive. “You can say that we explain something textually about almost anything, yet we run photos or graphics because they tend to be more specific and more detailed in developing an understanding of what’s causing all this anger,” Oppel told Michael Arrieta-Walden of the Portland Oregonian on February 12. “We didn’t put it on the front page, and that was a way of responding to reader interest without rubbing it in the noses of people who take offense.” Looking to past practice, the staff of the Philadelphia Inquirer agreed that the paper’s tradition was to push the envelope on using controversial images. (The Inquirer published, for example, grisly photos of the civilian contractors who were burned to death in Iraq in March of 2004.) The paper ran the turban cartoon on Page One on February 4 because, editor Amanda Bennett told the New York Times, it was clear that the caricatures were becoming “more, not less, newsworthy.” Among editors, only John Temple of the Rocky Mountain News expressed grave misgivings about the common American decision not to republish the cartoon. “Publishing offensive material doesn’t mean that a newspaper endorses it. It can mean that a newspaper takes seriously its role of informing the public,” he wrote in a February 11 explanation of the News’ decision to publish the cartoons. He noted the incongruity of an extensive New York Times piece, published February 8, by art critic Michael Kimmelman on the cartoons headlined, “A startling new lesson in the power of imagery,” which failed to show readers the powerful images. Bizarrely, that piece was illustrated not with the Danish cartoons but with an image of a collage featuring the Virgin Mary “with cutouts from pornographic magazines and shellacked clumps of elephant dung” that had been the focal point of a 1999 media dustup over blasphemy at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Temple went on to suggest that virtuous and disinterested editorial judgments to avoid offending Muslim sensibilities were not the only factors shaping American editorial policies. “I question whether we’re being given the full story about why some news organizations aren’t touching the cartoons. The missing word: Fear.” Temple then quoted an extra-ordinary outburst published in the Phoenix, a Boston weekly: “Simply stated, we are being terrorized and as deeply as we believe in the principle of free speech and a free press, we could not in good conscience place the men and women who work at the Phoenix and its related companies in physical jeopardy. As we feel forced, literally, to bend to maniacal pressure, this may be the darkest moment in our 40-year publishing history.” The reaction of American readers and viewers to all of this discussion of non-disclosure remains obscure, but there are signs that many were surprised and disappointed not to see at least some of the cartoons in the public prints. “Hundreds of readers have asked why the Post hasn’t reprinted the Danish cartoons of the prophet Muhammad that inflamed Muslims around the world, leading to deadly protests and the burning of embassies. Some readers have questioned the Post’s journalistic courage,” the Washington Post’s reader representative Debra Howell wrote in the newspaper on February 12. Editor Len Downie told Howell that the decision not to publish was a matter of journalistic judgment, not courage. For Fred Hiatt, the Post’s editorial page editor, the argument was more subtle. “I would not have chosen to publish them, given that they were designed to provoke and did not, in my opinion, add much to any important debate. “Should our calculation change once the story becomes big, because they cartoons are suddenly newsworthy? If it was essential to see them in order to understand, then maybe. But in this case, the dispute isn’t really about what the cartoons look like…it’s about the fact that he was depicted at all. The cartoons were easily explainable in words. Why reprint something you know will offend many of your readers?” Nevertheless, Post reader Martin Lawton asked, “Certainly, given the uproar, it seems incumbent to publish them now so readers can take a look for themselves and make their own decision. The cartoons have become The Story. How can the Post not show these images and keep a straight face?” Similar comments from readers are sprinkled throughout the stories written by various public editors, readers’ representatives, and ombudsmen. And indeed, even though most of the readers’ representatives strove mightily to explain why so few journalistic organizations published, many of them didn’t sound convinced that discretion was really the right decision. Howell, for example, closed her column by praising both the Post and, more tellingly, the Inquirer and the American-Statesman. “Being a first amendment freak, I support those newspapers right to publish the cartoons. Downie made a different and equally valid decision not to publish.” “The debate here is the same as everywhere: the right and obligation of a free press to publish news versus what is the right and responsible thing to do,” Armando Acuna, the Sacramento Bee’s Public Editor, wrote on February 12. “Let me say here, I respect the judgment of those at the paper, all with many years of experience, who decided against publishing the cartoons. I understand their reasons, which I will get into shortly. I just don’t agree with them. “It seems to me that once the cartoons evolved from their origin as a provocation and into an international news story, the paper had an obligation to show its readers what all the fuss was about. And, yes, that would have been offensive to some readers, especially Muslims, but a free and vigorous press is prone to do that to everybody at some point.” The 21st-century component of the story is that everyone involved knew—and many newspapers pointed out in self-justification—that anyone with an Internet connection could get access to the cartoons within a few seconds. So then there was a level-two debate about whether or not to identify web links where the cartoons could be found. As early as February 2, the Rocky Mountain News began identifying such links on the stories it ran, and many other outlets did as well. But still others declined to so, including National Public Radio, which would not even put them on its website. Indeed, notwithstanding wide-spread access to the web, in the course of the controversy it became clear that many Americans never managed to see the cartoons. One result was that they began popping up in unlikely places, including a biweekly newspaper published by the homeless in Cambridge, Massachusetts. As it turned out, the main venue for hard-copy publication in the United States was college newspapers, about 15 of which published some or, more often, all 12 cartoons. The biggest fallout was at the University of Illinois, where two student editors of the Daily Illini were fired by their colleagues after running them on February 9 without the permission of the paper’s editorial board. \ One of the fired editors told the Orange and Blue Observer, another student publication, that he had acted after speaking with students and learning that “many had not actually seen the cartoons, even though they had heard of the controversy surrounding them.” “When visiting campuses to lecture about comics, I have been astonished by how few people seem to have actually seen the cartoons,” Art Spiegelman wrote in a Harper’s Magazine cover story on the controversy in June. Harper’s reprinted not only the cartoons (with annotations and a “fatwa bomb meter” from Spiegelman), but also the original page from Jyllands-Posten. Many of the cartoons make no direct reference to the Prophet Muhammad at all, indeed several of them lampoon the newspaper for its contest. It’s the headline for the page, “Muhammed’s Face,” that creates the explosive context. “I’m not a believer, but I do truly believe that these now infamous and banal Danish cartoons need actually to be seen to be understood,” Spiegelman wrote. “If—as the currency of cliché has it—a picture is worth a thousand words, it often takes a thousand more to analyze and contextualize that picture. “It isn’t a question of adding insult to an open wound,” he added. “It’s a matter of demystifying the cartoons and maybe even robbing them of some of their venom. I believe that open discourse ultimately serves understanding and that repressing images gives them too much power.” Word.

|