|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Table of Contents Winter 2006

Quick Links:

From the Editor: Special

Supplement Winning Hearts and Minds in Kashmir

|

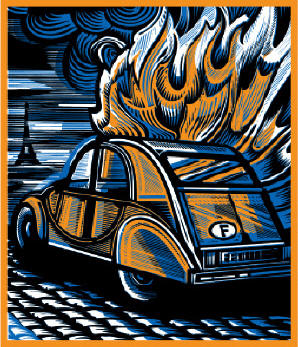

Liberté,

Egalité, Islam

The riots began with the deaths, on October 27, of Ziad Benna, 17, and Bouna Traor é, 15, of Clichy-sous-Bois, a gritty suburb (banlieue) north of Paris. Pursued by a police patrol probably on a routine inspection, the two youths took refuge in an electric transformer, where they were electrocuted.Over the next few days, confrontations took place between some residents of Clichy and law enforcement, but these were eased by community leaders. Then, on October 30, a tear gas grenade hurled in the vicinity of a local mosque filled with worshippers put a match to the powder. In the midst of the holy month of Ramadan, the violence that began in Clichy exploded across France. On November 8, a state of emergency was declared and extended for three months by vote of the National Assembly. From Lille in the north to Marseille in the south, the riots touched more than 300 communities, resulting in at least three dead and dozens of injured. Over three weeks, more than 14,000 buses, cars, trucks, and motorcycles were torched. Altogether, the damage to property was estimated at close to a quarter of a billion dollars. Some 11,200 law enforcement officers deployed around the country made 2,900 arrests. The rioters were young men whose parents, for the most part, had immigrated to France from North and sub-Saharan Africa in the 1950s and 1960s. Growing up in the bleak, isolated world of the banlieues, they had been denied access to good schools and decent jobs, subject to constant denigration, and excluded from the political system. They were the most visible evidence of France's failure to integrate its minority communities. That they were capable of violence came as no surprise. During the 1990s, disturbances had broken out in a number of banlieues. This was a significant turn from 1983 and 1984, when marches and demonstrations were held to protest racism and demand equality. But the extent of the uprising in the fall of 2005 pointed to a deeper crisis, a profound rupture in French society. Without memory, without dreams, without public voice, the rioters made fire their means of expression, and what it expressed was the bankruptcy of the country's universalist ideal of liberty, equality, and fraternity. Did it matter that most of the youths were Muslims, at least by heritage? Some leading right-wing voices in the American media were convinced that it did. Daniel Pipes, for example, began referring to the riots as the "French intifada," and he was not alone. For a while, Fox News reported the violence over a banner that read, "Muslim Riots." By and large, however, the mainstream media minimized the significance of Islam in telling the story. Nowhere was this more the case than in France itself, where the media ceaselessly underestimated the significance of the rioters' Muslim identity. Many of the leading newspapers and TV channels attacked the foreign media for allegedly reducing the riots to a "clash of civilizations" that served the politics of President Bush. The French media were, in this regard, largely driven by a political vision based on two or three themes: patterns of racism and discrimination, the collapse of the French model of social integration, and the failure of the banlieue as a model of urban planning. While perfectly evident, this left little room for an alternative to the explanation that the riots were simply the doing of notorious delinquents, organized gangs, or idle young people. The socioeconomic rhetoric that dominated the discussion never dealt with the malaise of a body of disenfranchised youth increasingly attracted by radical Muslim identities. Part of the problem was that because French Muslims have come to regard the French media as hostile territory (not least because of a prevailing tendency to associate the religion of Islam with the political agenda of Islamism), they often refuse to talk to reporters. During the riots, French television had great trouble finding young people in the banlieues to interview. To make matters worse, some journalists from the public network France 2 were attacked, and some others from the private network TF1 were roughed up and their vehicle set on fire. Not that this prevented foreign journalists from taking over a hotel in Clichy-sous-Bois and conducting business as usual - proof that the rioters were discriminating in their rage. It's worth noting as well that a certain spirit of competition took hold among the banlieues, with many youths boasting that they had gotten CNN, the BBC, or TF1 to come to their districts, while others "only" got the press or local television. Such "co-production of violence" by the media has been a subject of considerable interest to French sociologists. (The most blatant example of this occurred in 2000, when journalists working for the private network M6 were discovered to have actually paid some youths to torch a car so they could film it live.) Any enumeration of factors that contributed to the riots needs to take account of the provocations of the minister of the interior, Nicholas Sarkozy. During the three weeks of rioting, Sarkozy was constantly on television explaining his security policy and justifying his use of the word "scum" (racailles) to describe the rioters and his speaking of the need to "pressure clean" (nettoyer au karcher) the banlieues. These two formulas were the object of great public commotion, and were continually repeated on all the TV and radio stations, foreign and domestic. Uniquely, Sarkozy blamed fundamentalist Muslim groups in the banlieues for causing the riots - though he hurriedly denied this on an official trip to Muslim lands afterwards. Speaking on al-Jazeera while in Qatar, for example, he said, "I do not accept the association of Islam and the terrorists;" and "This was not a problem of Muslims, this was a problem of delinquents;" and "Islam is a religion of peace." While Sarkozy was pouring oil on the fire, the official leaders of the Muslim community in France were proving their ineffectuality. Most notably, the National Council of Muslims in France (NCMF), a representative body of ethnic Muslim groups established at Sarkozy's urging in 2003, made repeated appeals for calm, but to no avail. The NCMF has very little legitimacy with Muslims on the ground for two reasons. First, its chosen representatives are very much bound to Muslim regimes abroad at a time when most French Muslims feel themselves to be French. Second, the council has no real power to counteract the state's failures, such as through the appointment of Muslim chaplains in public schools, hospitals, prisons, and the military, and the establishment of private Muslim schools (which do not exist in France). Islam, with nearly five million adherents constituting eight per cent of the French population, is the second largest religion in the country, and its treatment on different terms from Christianity or Judaism has created a persistent sense of injustice among the Muslim faithful. By not addressing the unequal treatment, the NCMF failed to establish any credibility for itself. After the tear gas grenade was hurled near the Clichy-sous-Bois mosque, the council's president, Dr. Dalil Boubekeur of the Great Mosque of Paris, went there to show solidarity with the local imam, who had demanded a public apology from the president of the republic. Boubekeur was very badly received by the enraged community and had to be evacuated by security officers. Explaining that fumes inside the mosque had led many of the worshippers to believe that it had been tear-gassed in order to get them to leave, the Clichy imam, Abderrahman Bouhout, told me, "If a church or a synagogue had been attacked, the next day the minister would have come and issued a public apology...but we Muslims are not sufficiently respected." Acknowledging that he might have aggravated the situation by claiming, in scores of radio and television interviews, that the grenade had exploded inside rather than outside the mosque, Bouhout said that acting otherwise would have "changed nothing regarding the action and anger of Muslims gassed in the midst of praying. They are completely furious. When the apologies didn't come, it became possible for their children to want to avenge them." In fact, many of the youths I interviewed in and around Clichy insisted that the mosque had been attacked intentionally - a hypothesis that cannot be verified. Another Muslim institution that sought to calm the waters was the Union of the Islamic Organizations of France (UIOF). The strength of the UIOF is substantial - 250 affiliated mosques out of 1,000 - and its prestige, while declining, remains considerable, thanks to its opposition to the 2004 law prohibiting Muslim girls from wearing head coverings in public schools and its general defense of traditional Islam. Associated with the Muslim Brothers, the conservative Islamic movement that originated in Egypt, the UIOF has at its disposal the only center for theological education in Europe equipped to dispense religious decrees, or fatwas. On November 6, this center promulgated a special fatwa that read in part, "The UIOF expressly requests all Muslims in France to facilitate a return to civil peace, bearing in mind the following Koranic verse: God condemns destruction and disorder and rejects those who bring them about." This was widely disseminated on many French and Arabic websites as well as on al-Jazeera and other Arabic satellite television networks. Also calling for calm was the theologian Yusuf al-Qaradawi, a widely respected religious authority who heads the website www.Islamonline.net. Qaradawi also asked that the authorities quickly address the wounds caused by racism and employment discrimination. Besides these institutional leaders, a handful of prominent Muslim intellectuals and preachers such as Tariq Ramadan came forward to diagnose the implications of the riots for politics and for the social integration of increasingly radical Muslim minorities throughout Europe. Finally, a great array of anti-violence, pro-peace associations, both Islamic and leftist, vigorously denounced the French state and its injustices on behalf of the rioters, whose despair they said they understood. All these reactions were the visible face of the Muslim leadership in the media. But on the ground, where the cameras don't go, such figures have little weight compared to new leadership cadres that possess real legitimacy - indeed, that monopolize the moral capital in the banlieues. These include informal groups of Islamist hardliners (wahabis and salafists), but above all the members of the Muslim renewal association known as the Jama'at Tabligh. Although the media were largely unaware of it, the Tablighi did a lot to calm the violence in many neighborhoods. As one whom I found praying at the Clichy-Monfermeil mosque told me, "These youths who wish to smash everything, who respect nothing and no one, they are enraged. But they respect us because they see that we are on the right path and - when they need anything - money, help, someone to listen - they know that we are there and that we will help them, and that changes everything." Today, the fundamentalist preachers of the Tabligh movement can be found in more than 100 countries. They have been present in France since 1960, generally coming from India and Pakistan via London in groups of between three and five men (called Jama'a). They began by traveling around the country making followers among the first immigrants from North Africa in an effort to restore religious practice. But since the end of the 1980s, the movement has given priority to the immigrants' children, creating a web of local, regional, national, and transnational connections in all parts of France. This international Islamic network - the largest in the world according to the scholar Gilles Kepel - grows larger by the day. The Tablighi can be recognized by their appearance: beard, prayer beads, short wooden baton, and the short, sleeveless over-garment called the gandoura Their commitment is unconditional and their investment in preaching is powerful. The frequent efforts of their families to get them to reduce their involvement in the movement are generally fruitless. The newly militant male adherent cuts himself off from the world. Often, he stops watching television and listening to music, makes new friends, avoids sexual promiscuity, goes out little, and prays a lot. Like a hermit, he devotes himself to regular fasting, to meditation and study. He makes good use of his un- or underemployed status to improve his faith and practice. Animated by an extraordinary faith and little concerned with their public image, the rigorist new-style preachers of the Tabligh have, since the 1980s, devoted themselves above all to the banlieues, where the immigrant communities of largely Muslim origin seem easiest to bring to the right path. The sites of the riots of the 1990s such as Vaux en Velin, Mantes la Jolie, and La Courneuve were and remain prime loci of the Tabligh mission of leading back to God lost youth who by their destructive acts soil the image of the Muslim religion of which they are the unconscious emblems. During their missionary sorties in the banlieues, the Tablighi teach a rigorist and intransigent model of their religion based on the life of Muhammad. They look for lost souls in the darkness, netting "clients" in whom they seek to awaken a faith dormant in a consumer society where money is king. They appeal to them by evoking the conditions of their lives in the urban ghettos that the French republic seems to have abandoned. In my view, the Tablighi actually legitimize discrimination in order to encourage youth to join their ranks. They demand disengagement from politics. And while they never justify or encourage violence, they surf the riots to recruit the rioters. In effect, these new local leaders propose their form of Islam as a substitute for the French state. For the past decade, the Tabligh movement has been under the surveillance of the state intelligence service, which is particularly interested in the most zealous preachers - those who once spent four months in India or Pakistan with the presumed goal of fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan. The concern is that these will create more militants like the 150 young French Muslims whom French authorities have identified as having gone from training camps in Afghanistan to Pakistan, Bosnia, Chechnya, and Iraq - and who have, in a few cases, been linked to the 9/11 attacks on the United States. The majority of the latter came from the banlieues that were burning last fall. Those militants who passed from the Tabligh to violent Islamism do seem to have put some distance between themselves and the movement. Evidently, they have been hunted down by other recruiters. But the pronounced sectarianism of the Tablighi preachers I have encountered in the banlieues has led me to conclude that joining the Tabligh is a first step towards Islamist militancy. Three factors can be taken to explain the riots and the potential transition of riotous youth to radical Islam and even to terrorism: · · the stigmatization imposed by state authorities and institutions that are no longer performing their roles properly, and the role of the media in amplifying the stigmas; · the influence of radical foreign Muslim movements now present in Europe. What needs to be emphasized, however, is the existential situation of Muslims who feel themselves abandoned to a mythical and even paranoid religious identity. Institutional discrimination has generated a lasting hatred of the French state and its elites, which are seen as representing a larger Western political system that rejects Islam. The failure of social integration not only in France but also in many European countries has opened the door to radical Islam. The influence of a media discourse denouncing Islamophobia, Western imperialism, and the corruption of the Muslim states has done the rest. To be sure, Islam has been attacked unjustly and maligned here and there. But this hopeless discourse will change nothing and is at the same time an excellent ideological root on which to graft an Islam that is politicized and fanatical. France's 132-year history as a colonial power in the Islamic world helps explain the difficulty it has in treating its Muslim community on an equal footing with other citizens and other religions. The catastrophic result is the propagation of radical Muslim identities among those who have lost confidence in the state and its broken-down ideals. The reassuring words uttered last November by the French ambassador to the United States, Jean David Levitte, to the Council of American Islamic Relations, that "the riots have nothing to do with Islam," have no basis in truth. It was first of all a postcolonial vision of populations conceptualized as Muslim that confined them in these banlieues, these ethnic ghettos, that have become powder kegs of violence and reservoirs of potential terrorism. The line between Islam and the riots may not be direct but it is nonetheless very bright. The violence demands that France look clearly at its history, its political system, its treatment of immigrant minorities and their children. It is necessary to reach a state not merely of tolerance but of recognition and full citizenship, or there will be more serious crises in the future. When will France have the equivalent of a Colin Powell, a Jesse Jackson, or a Condeleezza Rice to counter the attraction the wretched feel to the nihilistic figure of Osama bin Laden? |