|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Table of Contents Fall 2005

Quick Links:

From the Editor: Covering Homosexuality in the Schools Cruisin' For a Scientological Bruisin'

|

The God Squadron

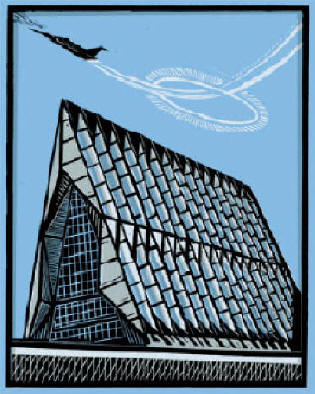

In November of 2004, just as the 2002-04 sexual harassment-and-assault scandal at the Air Force Academy seemed to be winding down, journalists began to shift their attention to a new problem: the climate of religious intolerance documented in a survey of cadets conducted by the academy the previous August. In the survey, half the respondents said they had heard some type of religious slur or joke, more than 30 percent cited unwelcome proselytizing by evangelical Christian cadets, and some non-Christian cadets charged that Christian cadets received preferential treatment. On November 17, Mike Soraghan of the Denver Post reported that after revealing the survey results, Superintendent John W. Rosa, Jr., told the academy’s Board of Visitors that a sensitivity training program was being developed to “ensure a climate free of discrimination and marginalization.” Early coverage of the new scandal was led by Colorado newspapers, including the Rocky Mountain News and the Colorado Springs Gazette as well as the Post. Indeed, during the eight months the academy remained under press scrutiny, the Gazette’s Pam Zubeck had the beat on the story, often writing several stories a week and scooping the bigger papers. Also notable for its coverage was the Air Force Times, an independent weekly owned by Gannett. Although the Times waited until May 2005 to take up the story, its thorough and objective reporting eventually provided its 60,000 subscribers—most of them active-duty and retired Air Force personnel—with a useful counterweight to the pronouncements of academy officials and Air Force higher-ups. It was in early 2005 that the national media started to focus on the story, beginning with Mindy Sink’s February 5 dispatch in the New York Times, which reported that academy officials were planning to begin “mandatory religious sensitivity sessions for cadets as well as faculty and staff members.” According to Sink, the sensitivity training program (called “Respecting the Spiritual Values of All People,” or RSVP) would feature 50-minute classes designed “to create a culture of tolerance and respect.” Religious intolerance at the academy, said senior chaplain Col. Michael Whittington, was “just a lack of respect…of understanding and sensitivity, not really malicious.” Soon other national papers were running stories on the RSVP program and reviewing what had led up to it. Among the events most frequently cited was an action taken by football coach Fisher DeBerry the day after Superintendent Rosa announced plans for sensitivity training. DeBerry installed a banner in the team’s locker room emblazoned with the Fellowship of Christian Athletes’ “Competitor’s Creed,” which read in part, “I am a Christian first and last….I am a member of Team Jesus Christ.”

In late April, after

it had been up and running for a month, the program was blasted by a Jewish

alumnus of the academy. “It’s Jim Crow, it’s lipstick on a pig, it’s eye

candy,” Mikey Weinstein ’77 told the Los Angeles Times April 20. “I

love the academy, but they are lying when they say it isn’t a systemic

problem.” Weinstein re- The same day Weinstein dropped his bombshell, the Gazette’s Zubeck revealed the existence of a report sent to Chaplain Whittington on July 30, 2004, by a Yale University Divinity School team that had observed cadet basic training in order to advise chaplains on pastoral care. The report, which the Gazette published in full and which other newspapers quoted extensively, cited “stridently Evangelical themes” observed during General Protestant Services attended by some 600 cadets. Chaplains leading the services had, for example, encouraged the cadets to witness to and proselytize fellow cadets, and to remind them that those not “born again will burn in the fires of hell.” The report expressed “concern that the overwhelmingly Evangelical tone of general Protestant worship encouraged religious divisions rather than fostering spiritual understanding among Basic Cadets.” On April 21, Dick Foster of the Rocky Mountain News quoted the Yale team leader, Professor Kristen J. Leslie, as saying that the RSVP program was only “one step” in addressing the problem. Although academy officials had announced that everyone at the school would undergo religious sensitivity training, Leslie claimed that the program was geared to “those with the least ability to affect [sic] change, that is, the cadets.” She added, “When you want change, you work with those with the most amount of power.” Over the next two months, newspaper coverage of the scandal intensified as other voices weighed in. On April 29, Jean Torkelson reported in the Rocky Mountain News that Americans United for Separation of Church and State had sent a report to Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld demanding an investigation of what it called the “atmosphere of discriminatory conduct” at the academy—“or face a lawsuit or congressional scrutiny.” On May 4, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and the New York Times published lengthy stories on the Pentagon’s decision to send an Air Force task force to investigate and make recommendations regarding the religious climate at the academy. Then, just as the task force was beginning its investigation, Capt. Melinda Morton, a chaplain who had worked closely with the Yale Divinity School team and helped develop the RSVP program, spoke out publicly for the first time in an interview with Laurie Goodstein in the May 12 New York Times. According to Goodstein, Morton “described a ‘systematic and pervasive’ problem of religious proselytizing at the academy” and revealed that the RSVP program had been “watered down” after being vetted by academy officials. The next day, T. R. Reid reported in the Washington Post that Morton had been “removed from administrative duties” earlier in the week, an action Morton interpreted as retribution for her public criticism of the academy but which an academy spokesman claimed was simply “a standard transition.” Congress got into the act in early June when the House appropriations committee amended a bill to urge the Air Force secretary (according to the June 9 Denver Post) to “develop a plan to ensure that the Air Force Academy maintains a climate free from coercive religious intimidation and inappropriate proselytizing by Air Force officials and others in the chain-of-command at the Air Force Academy.” “A Holy War in D.C.,” read the Rocky Mountain News headline on M.E. Sprengelmeyer’s June 21 story describing the full House debate on the amendment. “Work in the House of Representatives ground to a halt for 30 tense minutes” after Rep. John Hostettler (R-Ind.) charged Democrats with waging a “long war on Christianity” and “denigrating and demonizing Christians.” Democrats objected vociferously, and Hostettler eventually asked that his demonization remark be stricken from the record. After further deliberation, members approved a Republican version of the amendment omitting all criticism of the academy but requiring it to submit reports on its religious climate to lawmakers. On June 22, the Air Force task force released the report of its investigation at a Pentagon news conference. Newspaper accounts homed in on the finding that while “religious insensitivity” had been a problem at the academy, there had been no “overt religious discrimination.” “We believe that people were doing things that…were inappropriate,” task force head Lt. Gen Roger A. Brady told the New York Times June 23, but “they had the best intentions toward the cadets.” Writing the same day in the Colo-rado Springs Gazette, Pam Zubeck pointed to nine recommendations that the task force had issued to improve the religious climate at the academy and in the Air Force generally. These included the formulation of guidelines on permissible ways for service members to express their religious faith and the development of a program at the academy to teach “awareness and respect for diverse cultures and beliefs.” Reactions to the report varied widely, and, for the most part, predictably. On the one hand, a spokesman for Focus on the Family, the powerful evangelical organization headquartered near the academy in Colorado Springs, said, “We fervently hope that this ridiculous bias of a few against the religion of the majority—Christianity—will now cease.” On the other, Mikey Weinstein and Americans United criticized it for minimizing the problems at the academy. (The Anti-Defamation League, how--ever, approved its “substantive recommendations for reform.”) Congress was unappeased. “It is not a whitewash, but it does resemble milquetoast,” pronounced Rep. Steve Israel (D-N.Y.). Rep. John McHugh (R-N.Y.) announced that the House Armed Services Committee would hold hearings, while Sen. Ken Salazar (D-Col.) called upon the Senate Armed Services Committee to do the same. Newspapers were even less impressed. From the first, editorialists agreed that a government-run institution should not endorse religion and that religious intolerance at the academy had to be dealt with promptly and decisively. The April 21 Portland (Maine) Press Herald and the April 25 Roanoke Times and World News called attention to the fact that high-ranking officers had been involved in the elevation of evangelical Christianity above other religions. The May 7 Denver Post found religious intolerance “especially disturbing when it comes from the brass.” Early on, papers like the Denver Post and Houston Chronicle had expressed some hope for a timely in-house remedy. But after Chaplain Morton spoke out, editorial opinion stiffened across the board. “It is hard to believe that there can be true reform from within,” declared the New York Times on May 14. “It is time for the higher chain of command to deproselytize this institution of national defense.” Two days later, the Air Force Times expressed skepticism that academy officials could investigate and reform themselves, especially since many of them were alleged to have contributed to the scandal: “With charges being made against cadets, faculty, leadership and even chaplains, an independent review of the matter is the only way to definitively determine what violations have occurred and what changes should be made.” On May 19, the Chattanooga Times Free Press doubted that the task force report would be “unbiased.” Observed the paper, “The Air Force, like other institutions, has a history of protecting its own.” Meanwhile, a June 4 Washington Post editorial criticized the task force for virtually ignoring “those who have been most outspoken” about the academy’s religious climate, namely Morton, Weinstein, and Leslie. Release of the report led the Denver Post and the Roanoke Times and World News to note the disparity between the finding of no “overt religious discrimination” and the numerous instances of religious intolerance cited by the Yale Divinity School team as well as other groups and individuals. The report “goes on for page after page describing cases of obvious and overt religious bias,” noted the June 23 New York Times, but “tosses all of these off as ‘perceived bias,’ as if the blame lies with the victims and not the offenders, and throws up a fog of implausible excuses, like ‘a lack of awareness’ of what is impermissible behavior by military officers.” For defense of the academy on the opinion pages, it was necessary to turn to the occasional conservative columnist or outside contributor. For example, James Kelso, a retired Air Force officer, contended in the June 13 Atlanta Journal-Constitution that “what the cadets and others at the academy are doing is totally within the boundaries of the Constitution.” From the outset, reporters pursuing the story had, not surprisingly, to contend with authorities intent on suppressing information on the religious situation within the academy. All interviews with cadets, faculty, and staff had to be approved by the academy’s public affairs office, and, as early as November 18, 2004, Zubeck reported that cadets and graduates feared “reprisal” for talking to her and therefore requested anonymity. After Chaplain Morton spoke up without authorization—and was transferred—such fears became even more pronounced. New York Times reporter Goodstein noted in her May 12 story that “nearly all students and faculty members contacted independently…said they were afraid to speak because it could harm their careers.” Lacking direct access to most academy personnel, reporters had to rely for information on “academy spokespersons” who gave the leadership’s official position and individuals and groups outside the academy who voiced criticism of the religious climate. But if there was a shortcoming to the coverage, it resulted not from the absence of inside accounts but from journalists’ failure to set the scandal in larger context. Although some news stories and editorials suggested links between religious intolerance at the academy and earlier scandals or with the ongoing “culture war” in civilian society, these subjects received little or no elaboration. More importantly, most reporters remained narrowly focused on the Air Force Academy despite speculation in some quarters that problems might be found elsewhere in the military. Recounting a meeting with Superintendent Rosa, Anti-Defamation League national director Abraham Foxman told the Rocky Mountain News on June 4 that “the Air Force Academy may not be unique”—but the paper left the hint dangling. Several reporters did enlarge their focus. In a lengthy story in the Air Force Times May 16, Bryant Jordan put the academy scandal within the larger context of evangelicals in the military chaplaincy. In the July 12 New York Times, Laurie Goodstein documented the already large and growing number of evangelical chaplains in the Air Force. And in a report on National Public Radio July 27, Jeff Brady reported on evangelical influence in the Army and Navy chaplain corps as well as in the Air Force chaplaincy. I had the pleasure of talking with all three of these journalists, who sought me out because of my book on evangelicals and the U.S. military from 1942 to 1993. In my view, the Air Force Academy story represents a significant new chapter in the history I traced. In the latter part of the 20th century, military evangelicals were never shy about asserting themselves, but they were nowhere near as brazen as today’s academy faculty and administration—nor nearly as powerful. Evangelicals began their spiritual offensive in the armed forces in the 1940s, when the newly established National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) and other conservative Christian denominations and churches endorsed chaplains to serve, in effect, as missionaries to the military. Like all of the other men and women who joined the chaplaincies, the evangelicals remained clergymen of their own denominations or faith groups, but, in recognition of the religious diversity of the armed forces, they were expected to cooperate with other chaplains in ministering to service men and women of many different religious persuasions. This arrangement, termed “cooperative pluralism” by historian Richard G. Hutcheson, was designed to discourage chaplains from espousing narrowly denominational or sectarian views. Ecumenical accommodation was the order of the day. Beginning in the early 1950s, evangelical chaplains, aided by other military evangelicals and civilian groups like the NAE, challenged the military leadership (which at the time was predominantly mainline Protestant and Catholic), denouncing the ecumenical and theologically liberal orientation of the armed forces’ religious programs. Some evangelical chaplains refused to participate in the General Protestant Service or other interdenominational or interfaith assemblies, while others protested against the curriculum used in armed forces Sunday schools. Cooperation with such programs, they insisted, would compromise their faith. Evangelical chaplains were per-mitted to withhold participation, because, at the same time that the chaplaincies urged cooperative pluralism, they also supported, even encouraged, denominational loyalty. For example, the 1977 Army chaplains’ field manual stated that chaplains were to perform their duties “in accord with their conscience and the principles of their church.” By the 1960s, evangelical chap-lains had become somewhat less confrontational. Although they did not succeed in abolishing ecumenism, they found ways of circumventing it, such as by incorporating into the General Protestant Service evangelistic preaching designed to provoke “decisions for Christ,” or by adding an “altar call” or “invitation” at its conclusion. They also seized opportunities offered by the military leadership to organize Bible studies, prayer meetings, revivals, and retreats, as well as separate denominational services in which they were free to promote their sectarian beliefs. Still, under the regime of co-operative pluralism, chaplains were prohibited from proselytizing, at least to those who belonged to other faith communities: Evangelizing the “unchurched” was acceptable, but “sheep stealing” was not. Yet, like all evangelicals, evangelical chaplains believed they were called by God to carry out the Great Commission handed down by Jesus in Matthew 28:19—to “go…and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.” Many, perhaps most, evangelical chaplains flouted the no-proselytizing rule. Lay evangelicals in the military and parachurch groups such as the Navigators, the Officers’ Christian Union, and Campus Crusade for Christ Military Ministry were, of course, unhampered by the system of cooperative pluralism. Aggressive proselytizers, they converted hundreds of service men and women. Only when such zealous proselytizers provoked a public outcry did the leadership take action. In the early 1970s, Gen. Ralph E. Haines, the commander of the Continental Army Command, began making numerous speeches, in uniform, to civilian groups around the country, in which he referred to himself as a “private in the Lord’s army” and to God as his “Commander-in-chief”; boasted of giving his “personal testimony to Jesus Christ” throughout the army; and declared that “the Lord is using me to rekindle spiritual zeal and moral awareness…at scores of military installations” across the United States. In 1973, the Pentagon asked Haines to retire six months early. By then, evangelicals had reached a point of accommodation with the military leadership, thanks in large measure to two factors. First, unlike the mainline denominations, evangelicals had wholeheartedly supported the Vietnam War. And second, the armed forces now included many officers who were themselves either professed born-again Christians or sympathetic to evangelicalism. Over the next couple of decades, the influence of evangelicals in the armed services grew incrementally alongside their increasing share of the military population. But they never gained the kind of dominance within a military installation that they appear to have acquired at the Air Force Academy. At the academy, many, if not most, of the leaders appear to be evangelicals. The commandant of cadets, Brig. Gen. Johnny A. Weida, has proudly described himself as a born-again Christian, and the academy’s Board of Visitors includes professed evangelicals. Among the academy’s 16 chaplains, Chaplain Morton told the Washington Post May 13, the evangelicals have “a much bigger voice.” This religious dominance at the academy gave evangelicals free rein to take their longstanding spiritual offensive to a new level. Not content to limit their efforts to proselytizing, they began to encourage a climate of religious intolerance and to practice religious discrimination against non-evangelicals—in effect, creating an “establishment of (evangelical) religion” at the academy. That such a thing should have happened at the Air Force Academy is, in one sense, no surprise. In recent years, Colorado Springs has become the Mecca of American evangelicalism, home to countless evangelical lobbies and non-profits, of which the largest and most important is James Dobson’s Focus on the Family. Dobson, who was engaged to help develop an army program for families over 20 years ago, moved his organization to Colorado Springs in 1991 in no small part because of the Air Force Academy and the conservative values he saw it embodying. It’s worth mentioning, as well, that the academy occupies a special place in the American religious landscape. Its modernist chapel, built in 1956, has become one of the most famous ecclesiastical buildings in the country and the most visited tourist site in Colorado. “Massed,” as one website puts it, “like a phalanx of fighter jets shooting up into the sky,” and featuring separate Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish worship areas, the chapel is a kind of paean to the civil religion that came into being to fight the Cold War. The takeover of this place by evangelical Protestantism carries some heavy symbolic freight. On August 29, the Air Force issued new guidelines instructing officers to make sure that nothing they say or do be “construed as either official endorsement or disapproval of the decisions of individuals to hold particular religious beliefs or to hold no religious beliefs.” While allowing for “a brief nonsectarian prayer” at special ceremonies or under “extraordinary circumstances,” the guidelines discourage public prayers at official Air Force events outside of worship services. It remains to be seen whether and to what extent the guidelines—along with other corrective action—will bring about a change in the evangelical religious regime at the academy. On October 6, some additional pressure was brought to bear when Weinstein filed a lawsuit against the Air Force, claiming that senior officers and cadets had illegally imposed Christianity on others at the academy. Last spring, in a moment of candor, Superintendent Rosa told the Anti-Defamation League that the problem at the academy would take six years to resolve. But even that may be optimistic. Not only do evangelicals believe that their brand of Christianity is the only true one and that all other religions are half-truths at best, they are also convinced they have been commissioned by God to bring the rest of the world to accept their belief. This kind of thinking does not encourage tolerance of or respect for other religions. One thing seems certain. The evangelical mission to the military is not likely to disappear any time soon. On August 30, the Washington Post published a lengthy article by reporter Alan Cooperman on how the growing influence of evangelicals was “roiling the military chaplain corps.” Cooperman reported that whereas mainline Protestant chaplains are increasingly difficult to recruit, and Catholic priests are in shorter and shorter supply, “many evangelical denominations place a high priority on supplying chaplains to the military.” As much as anything else, the force of the story lay in the numbers. According to Pentagon data, Southern Baptists have become the single largest source of military chaplains, with 451 out of 2,860 on active duty. Active-duty Catholic chaplains now number only 355. Bear in mind that of the 1.4 million people on active duty in the military, 300,000 identify themselves as Catholic, 18,000 as Southern Baptist. |