RELIGION IN THE NEWS |

||

| Table

of Contents Spring 2002 Quick Links:

|

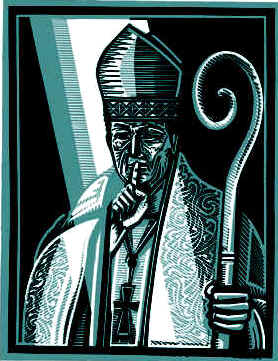

The Cardinal and the Globe by J. Ashe Reardon Cardinal Bernard Law and the Boston Globe have a history. Ten years ago, allegations of sexual abuse by James R. Porter, a former Roman Catholic priest formerly assigned to the Catholic diocese of Fall River, caused a furor in Massachusetts. The story lines, the pattern of coverage, and the focus on the church’s secretive internal personnel practices show impressive continuity from 1992 and 2002. The Porter story broke in early May 1992 when a victim, Frank Fitzpatrick, released a tape to a Boston TV station in which Porter admitted to molesting "anywhere, you know, from fifty to a hundred [children], I guess." The Globe and its Spotlight Team of investigative reporters immediately grabbed the lead in covering the story of Porter’s transfer to three different Fall River parishes during the 1960s amid a long series of allegations of sexual misconduct. In 1992, the "priest pedophile" was already a familiar object of journalistic attention and Porter rapidly emerged as an exemplar of the predator priest who preyed on scores of children. The Globe jumped on the story, focusing on the Fall River diocese’s evident practice of stonewalling complaints about Porter and transferring him from parish to parish. "There’s no question the church covered it up," Frank Fitzpatrick, a Porter victim whose ad in a local paper inquiring about other victims helped bring the story to the public, complained in a Globe story published on May 8. "When sexual misconduct surfaces, the church has chosen to simply move the priest to another parish," said Jeffrey Anderson, a lawyer who represented sexual abuse victims. This tack in the coverage—and the Globe’s effort to raise questions about whether similar problems of sexual abuse and cover-up were occurring in the Boston archdiocese—drew an unwilling Cardinal Bernard Law into the center of the controversy. To some degree Law’s role as a principal player was forced on him. In the winter and spring of 1992, there was no sitting bishop in Fall River and Law was acting as the nominal supervisor of the diocese. But the crisis, and the Globe’s aggressive approach, quickly got under Law’s skin. Frustration may, however, have gotten the best of both parties. On May 24, a story by Steve Marantz ran under the headline, "Law Raps Ex-Priest Coverage," in which he quoted a statement made by Law at a rally in the Roxbury neighborhood. The quote, subsequently fairly famous, was "We call down God’s power on our business leaders, and political leaders and community leaders. By all means we call down God’s power on the media, particularly the Globe." Was Law calling on the Lord to smite the Globe? Appearances may be deceiving. A review of the coverage suggests that Marantz misquoted Law. The reporter evidently dispatched to the rally to get a quote from Law on the Porter case, was rebuffed. He then appears to have spun Law’s invocation of Boston’s civic forces, including the Globe, to play a positive role in stopping youth violence into a comment on the Porter case. Three days later, a follow-up story by the Globe’s religion writer, James Franklin, attempted some cleanup. Headlined "The Cardinal and the News Media," the story gingerly suggested Law actually had been talking about the city’s inadequate response to the current crisis of youth violence. That said, Franklin veered back, criticizing Law’s "impulsive, spontaneous" remarks. "By falling back on the institutional defensiveness of the Catholic Church," Franklin continued, "Cardinal Law seemed to turn his back on the anguish" of the men and women who charge they were molested by Porter. The Globe—and others—felt entitled to a public explanation, which Law refused to give. On June 25, Law announced that the archdiocese was "systematically reviewing its files to ascertain if there are indications that warrant further assessment." As is now known, by 1992 Law had already been deeply involved for years in the handling of dozens of cases of priests with records of sexual abuse. The Globe pressed its intense dissatisfaction over Law’s less-than-forthcoming approach in a series of more than two-dozen pieces that carried on into the fall. Franklin’s July 12 dispatch (headlined "US Diocese Lack Policy for Cases of Sex Abuse") drew a connection with a 1985 report by a national commission appointed by the Catholic bishops that urged uniform procedures for dealing with sexual misconduct by priests. The article scoffed at the claims of Boston church officials that "they have only recently learned about the extent of sexual abuse by clergy and methods to handle it." Several months of coverage followed in which the newspaper pieced together victims’ accounts of Porter’s years of abuse. Law then released first a draft and then the final version of a new Boston archdiocese’s policy on handling sexual misconduct claims. In January 1993, Law set up a board consisting of five lay members and four clerics to review future complaints of sexual abuse by priests. The archdiocese’s new policy emphasized that no cleric found guilty would be given an assignment "which places children at risk." Law retained for himself final authority to decide how to deal with errant priests. He pledged then to report sexual misconduct "in accordance with the law." In retrospect, the statement seems misleading, given that Massachusetts law did not require the church to report incidents of sexual misconduct to civil authorities. The Globe criticized Law’s new policy immediately. A January 16 editorial called it a lost opportunity to communicate with parishioners and the public that it understands the depth of the problem" of sexual misconduct by Catholic priests. At the core of the critique was Law’s refusal to bring sexual abuse out from the realm of internal forums and civil law. By way of comparison, when Chicago Archbishop Joseph Bernadin was confronted with a similar spate of abuse cases in late 1991 he named an attorney to work full-time as a "professional fitness review administrator" for the archdiocese and designated him as a "mandated reporter" of abuse to the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services. One of the reporters on the Spotlight Team that produced January’s series on the Geoghan case was also a veteran of the Porter story. Back in 1992, Stephen Kurkjian wrote several articles detailing the staggering lawsuits filed against the Fall River diocese, and on diocesan personnel records indicating that Church officials allowed Porter to serve as a priest in four states, in close proximity to children, "even though they were fully aware of his habitual sexual molestation of youths." Memories are long in Boston. |

|