|

RELIGION IN THE NEWS |

|

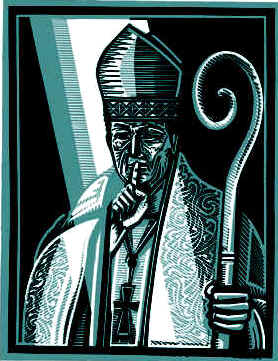

The

Scandal of Secrecy On January 6, a week before a defrocked Catholic priest was set to be tried for molesting a 10 year-old boy, the Boston Globe’s Spotlight investigative team rolled out a devastating series on clerical sexual abuse of children and the hierarchy’s chronic failure to treat priestly misconduct as criminal. "Since the mid-1990s," the main story’s lede began, "more than 130 people have come forward with horrific childhood tales about how former priest John J. Geoghan allegedly fondled or raped them during a three-decade spree through a half-dozen Greater Boston parishes. "For decades, within the US Catholic Church, sexual misbehavior by priests was shrouded in secrecy—at every level," the Globe reported. "Abusive priests—Geoghan among them—often instructed traumatized youngsters to say nothing about what had been done to them. Parents who learned of the abuse, often wracked by shame, guilt, and denial, tried to forget what the church had done. The few who complained were invariably urged to keep silent. And pastors and bishops, meanwhile, viewed the abuse as a sin for which priests could repent rather than as a compulsion they might be unable to control." Thus broke the latest phase of the most sweeping, costly, and damaging religious scandal in the history of the United States, the seemingly endless 15-year cycle of stories about the Catholic Church’s struggle to confront and deal with the sexual abuse of children by its clergy. In Massachusetts, the public response was extraordinary. "The daily revelations about priests who sexually abuse children seems to be sucking the very air out of this community," the Boston Herald editorialized a few weeks into the scandal. First Boston, then New England, and then, by late February, many parts of the nation were caught up in a continuing wave of breaking news. At Easter, the story was still unfolding and the newsweeklies were publishing covers with hyperbolic headlines like "Can the Church Save Itself?" "‘It’s not often that we witness the death of a mystique,’ US News & World Report quoted Daniel Maguire, a moral theologian at Marquette University, on April 1. "Catholic priests have had the highest possible prestige. Now, you have sick priests who preyed on children and a hierarchy that aided and abetted the molestation of children through a deliberate coverup." This phase of the longer crisis was not, however, generated by reports of new cases of sexual abuse. The charges against Geoghan, for example, were already familiar in Massachusetts. Almost all of the alleged assaults in the Geoghan case took place before 1993, with many dating as far back as the mid-1960s. The Globe, the Boston Herald and the weekly Boston Phoenix had reported frequently about the case at several points over the previous ten years. But a flat assertion is in order: It was the Boston Globe that drove this story. Beginning in 1992 with intensive coverage of the James Porter case in neighboring Fall River (see sidebar), the Globe has consistently kept its eye on cases of clerical abuse. For example, because there were both criminal charges and civil suits before the Massachusetts courts, the Geoghan case produced ongoing coverage through the middle and late 1990s. This time, the focus was the Catholic Church’s leadership. The headline for the Globe’s first-day story distilled the essence of the charge: "Church Allowed Abuse by Priest for Years. Aware of Geoghan’s Record, Archdiocese Still Shuttled Him from Parish to Parish." The Globe’s key sources were a small group of plaintiff’s lawyers who were building cases against Geoghan, other errant priests, and the archdiocese. The newspaper’s own lawyers entered the fray to oppose a September 2000 ruling by Suffolk Superior Court Judge James McHugh that granted an archdiocesan request to give both plaintiffs and defendants in the Geoghan case the right to classify any documents involved in litigation as confidential—an unusual decision that conformed to a long history of deferential treatment afforded the Catholic church by Massachusetts institutions. The key break in the story came on November 30, when another Suffolk Superior Court judge, Constance M. Sweeney, ordered the release of thousands of internal church documents gathered during the legal process of discovery in dozens of civil suits against Geoghan. Sweeney ruled that her colleague’s previous order might have "the unintended effect of impeding the access of the public and the press to certain aspects of the case." On January 6, the Spotlight Team turned up the heat. The first weekend’s stories painted a portrait of Geoghan as a persistent predator over the course of his 30-year priesthood and of his passage through six parish assignments and repeated cycles of psychiatric treatment and reinstatement. The initial package included stark accounts by Geoghan’s victims and revealed that Cardinal Bernard F. Law—continuing a pattern set early in Geoghan’s career—had reassigned him to a new parish in 1984 even though he had received complaints about the priest’s misconduct with boys. Inexplicably, the pastor at Geoghan’s new parish in the affluent suburb of Weston placed him in charge of altar boys and youth groups. Complaints about the priest continued until Geoghan was removed from parish ministry in 1993 and finally defrocked in 1998. "The cardinal and five other bishops have been accused of negligence in many of the civil suits for allegedly knowing of Geoghan’s abuse and doing nothing to stop it," the Spotlight Team reported. The Boston hierarchy should have known the day of reckoning was at hand. After reviewing internal church documents culled from court files, the Globe showed that Law and other bishops had received reports from national church commissions as early as 1984 indicating that pedophilia is a chronic disorder, with high rates of repeat offenses, even for those who had received intensive psychiatric treatment. "Until recently," according to the first-day story, "the church also had little to fear from the courts." But that has changed, as predicted in a 1985 confidential report on priest abuse prepared at the urging of some of the nation’s top bishops, Law among them. "Our dependence in the past on Roman Catholic judges and attorneys protecting the Diocese and clerics is GONE," the report said. Among the thousands of court documents finally released on January 26 was a letter written to Law in December 1984, a month after Geoghan’s reassignment to Weston. In it, Auxiliary Bishop John D’Arcy challenged the wisdom of the assignment in light of Geoghan’s "history of homosexual involvement with young boys." In the weeks after the story broke, the Globe had nine reporters working full-time on the story. Devastating follow-up stories appeared almost daily. As late as the end of March, the Globe often printed four or five stories a day on various aspects of the scandal and its national and global ramifications. This ever-extending chain of stories, and the huge collection of documents released on January 26 by the court, profoundly undermined Law’s credibility. The most damaging blow was self-inflicted. In July of 2001, as the Geoghan case moved toward trial and legal maneuvering over the release of documents intensified, Law published a column in his own archdiocesan newspaper defending his record in handing sexual misconduct charges. "Never was there an effort on my part to shift a problem from one place to the next," he wrote in the July 27 Boston Pilot. The first weekend’s stories gave the lie to that claim. The archdiocese’s first response to the story was to struggle to maintain its pattern of public silence. "Donna Morrissey, a spokeswoman for Law, said the cardinal and other church officials would not respond to questions about Geoghan," the Globe reported on January 6. "Morrissey said the church had no interest in knowing what the Globe’s questions would be." That facade cracked quickly. On January 9, Law faced reporters for the first time to discuss the Geoghan case. Confronted by undeniable internal documents, Law apologized "to all victims of sex abuse by priests, to Geoghan’s alleged victims, and "particularly those who were abused in assignments which I made." At the same press conference, Law promised to abandon his internal policy for handing priests charged with sexual misconduct. Instead of returning many to ministry after psychiatric treatment, Law pledged "a policy of zero tolerance for such behavior. Any priest known to have sexually abused a minor simply will not function as a priest in any way in this Archdiocese." Within days, new "zero tolerance" policies were announced in Philadelphia and Los Angeles, and in all three cities reports followed of priests being removed from ministry as a result of the stricter policy. Law then went about the task of establishing a commission of lay and academic experts to advise him on how to proceed. As January passed, the Globe’s follow-ups continued to deliver heavy blows, reporting (for example) that in the 1980s Law had relied on medical advice in repeatedly reinstating Geoghan to parish duty—advice that turned out to come from Geoghan’s general practitioner and a psychiatrist who had never treated another patient who sexually abused children. Some of the revelations bordered on the surreal. On January 24, the Globe published excerpts from a letter that Law had written to Geoghan in 1996—three years after he had removed him from parish ministry and in a period when you knew that Geoghan was under prosecutorial scrutiny. "Yours has been an effective life of ministry, sadly impaired by illness…God bless you, Jack." Pounded relentlessly, Law at the end of the month issued an even more remorseful statement apologizing for his decisions, but refusing to resign. "In the terrible instances of sexual abuse, the Archdiocese of Boston has failed to protect one of our most precious gifts, our children. As Archbishop, it was and is my responsibility to ensure that our parishes be safe havens for our children," he wrote. "In retrospect, I acknowledge that, albeit unintentionally, I have failed in that responsibility. The judgments I made, while made in good faith, were tragically wrong." Polls reported that Boston Catholics were deeply critical of Law’s handling of clerical sexual abuse and evenly divided over whether he should resign. The overwhelming sense conveyed in stories in the Globe, the Herald, the Quincy Patriot-Ledger, local news broadcasts, radio talk shows, and on street corners was that Boston’s Catholics were furious, truly off the reservation. "Cardinal Bernard Law can stay or go as archbishop of Boston," Globe columnist Joan Vennochi wrote on January 29. "It really doesn’t matter. Like Bill Clinton after Monica Lewinsky, he stands stripped of moral authority. He may cling to the office, but the power is gone." Vennochi returned to the scandal on March 12. "For the first time ever, Boston’s political and business establishment is standing up to Cardinal Bernard F. Law and all he represents in the Catholic Church. That does not happen easily in this city. It comes in recognition of two factors: the shocking scope of the revelations and the awareness that the media, local and now national, are not backing away from the original story or further developments." Other Globe columnists—Eileen McNamara, Ellen Goodman, Adrian Walker, and, most of all, Derrick Jackson—also blasted away. Mc-Namara’s January 27 column began, "Cardinal Law is right about one thing. His resignation would not cure what ails the Roman Catholic Church." Within a few graphs she shifted to a vigorous critique of priestly celibacy and the refusal of the church to ordain women as priests. Former Boston Mayor and Ambassador to the Vatican Raymond Flynn was virtually the only prominent figure to mount any public defense of Law. Appearing on ABC News’ "Nightline" February 21, Flynn complained that the media "should not try to bring down the Catholic church here because of a handful of bad apples in the barrel." When host Ted Koppel responded that he didn’t think "anyone’s trying to bring down the Catholic church," Flynn snapped. "Oh you haven’t been up in Boston then, Ted. You should take a look at the Boston Globe every single day." As January turned to February, the focus of coverage in Boston shifted from whether Law should resign to the numbers of priests involved. "The newspapers speculate that as many as 50 priests may eventually be accused," John O’Sullivan of United Press International wrote on January 30. "That is almost certainly a large exaggeration. But suppose that the true figure is five. Would that not be shocking enough?" Within a week, under pressure from press and prosecutors, the archdiocese admitted that its files contained allegations against "more than 70" priests over the past 40 years. The eventual total passed 90, with hundreds of new allegations still to be evaluated surfacing in February and March. Then journalists outside Boston began to ask questions at home, rather than merely covering the spectacle in Boston. Newspapers (mostly in Catholic population centers) like the Philadelphia Inquirer, Newsday, the Hartford Courant, the Los Angeles Times, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the Cleveland Plain-Dealer, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and the Milwaukee Journal began to break stories in their own coverage areas. The story also got considerable attention on NPR, and the network and cable news broadcasts, especially in the week before Easter. ABC’s "Nightline" devoted three shows to the story in February and March. At the same time, the papers in Baltimore, Buffalo, Cleveland, Minneapolis, and Seattle reported that local archdioceses were expressing confidence that no priest pedophiles were serving there. Surveying the scene, Laurie Goodstein and Alessandra Stanley wrote in the New York Times on March 17 that the "sexual abuse scandal engulfing the Catholic Church, far from being nearly over, has only begun. Across the country, in an effort to restore credibility, many dioceses are volunteering to turn over their records to prosecutors. The publicity is emboldening more people to step forward with accusations of sexual abuse. The news media daily are exposing new cases of priest pedophiles and new reports of cover-ups." After the first wave of stories broke in the late 1980s, most American dioceses adopted new policies governing their response to allegations of priestly misconduct. While these policies vary considerably in detail, they fall into two general camps. On the one hand, there were policies produced in the wake of grave scandals that mandate prompt reporting of allegations to law enforcement officials, promise openness, and set up special, lay-dominated commissions to handle investigations and to make recommendations about how to handle cases of false accusations or allegations that fell short of the standard of proof required for criminal prosecution. The model here has been the policy established by Cardinal Joseph Bernadin in 1992, which established a nine-member commission with six lay members, including a victim of priestly sexual misconduct and the parent of a victim. The Belleville, Illinois policy went even farther, mandating public disclosure of allegations and setting up a practice of the bishop appearing at Sunday mass in any parish where a priest has been suspended to discuss the investigation and to answer questions. Some even believe that major cleanups rooted out problem priests in diocese like Chicago, Minneapolis, Baltimore, and Seattle during the early 1990s. On the other hand, many policies—like that adopted in Boston in 1993—were crafted to reserve to the hierarchy the right to determine internally which allegations were credible and how and whether priests returning from psychiatric treatment could or should be reinstated in some form of ministry. By and large, the biggest blowups in early 2002 have occurred in dioceses that share the Boston model of hierarchical control and where strenuous efforts were made to keep allegations and litigation secret, often through requiring confidentiality requirements as part of legal settlements. There are also those, such as Mark Chopko, the general counsel of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCC) who was frequently interviewed on the scandal in February and March, who have said that most of the new policies have been implemented quite effectively over the past decade. Chopko cited many cases in which fresh allegations have led rapidly to the arrest of priests and the termination of their public ministries. So the optimistic scenario was that stories like the Boston Globe’s, which stand largely on internal church documents from the 1980s and early 1990s, give an accurate but outdated picture of hierarchical indifference to the problem. If so, the burden is on the bishops to be far more open then most of them have wanted to be about their responses to instances of misconduct. Between January and March, several major sub-themes floated in and out of the coverage. • Sheer amazement that so many bishops and other senior administrators could countenance routine policies of turning a blind eye to sexual assaults on children. Columnist Kenneth Moynihan’s remarks in the January 30 Worcester Telegram & Gazette conveyed the general sense of this: "I think I can understand most the key elements in the story about Catholic priests abusing children, getting caught, and then being repeatedly placed in positions where they could, and did, abuse more children. The part I have the hardest time making sense of is what the bishops were thinking when they chose to risk reassigning these men to parish ministry." Almost no one within the church hierarchy has attempted to explain that publicly—even Pope John Paul II fell back on an appeal to "the mystery of evil" to describe the source of priestly misconduct. The sole exception I could discover was Bishop Donald Wuerl of Pittsburgh, whose remarks at a March 28 mass were covered in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Wuerl, reporter Ann Rodgers-Melnick wrote, "tried to explain that bishops who returned child molesters to parishes years ago did not act out of malice. Twenty years ago society did not recognize that the desire for sexual contact with minors was a psychological compulsion, so bishops treated it as they would any other moral problem requiring repentance and forgiveness." • Debate over the relationship between priestly celibacy and the sex scandals. In the early weeks of the story, many of those quoted, especially Catholic lay people, quickly blamed the church’s celibacy requirement for causing the problem. That explanation, especially popular on the Catholic left, viewed celibacy as the foundation of a closed and secretive clerical culture, one that motivates priests and bishops to hide scandal and to protect one another. For reasons not entirely clear, celibacy was cited as the chief problem less often later in January and February. In fact, during that period, celibacy found its defenders, including psychiatrists. "An all-too-facile solution I have heard repeatedly suggested boils down to this formula: If church officials want to avoid sexual abuse, all they need to do is eliminate the celibacy requirement," the Jesuit psychiatrist James Gill wrote in a widely-reprinted column in the February 17 Hartford Courant. But "it isn’t celibacy that creates pedophiles. Think of the tens of thousands of American children damaged in incestuous situations in which parents are responsible for the sexual exploitation of their own children." A bit later, however, the liberal critique of celibacy bounced back into prominence. The most forceful prompting came from an unlikely source, the Boston Pilot, which on March 15 published an extraordinary 28-page edition focusing entirely on the crisis in the archdiocese. Along with the spectacle of a Catholic newspaper carrying a lengthy account of a string of parish representatives to an archdiocesan convocation calling for their cardinal’s resignation, the paper editorialized on "Questions That Must Be Faced." The first question was "Should celibacy continue to be a normative condition for the diocesan priesthood?" On March 24, the Boston Globe Magazine carried Gary Wills’ learned polemic, "The Case Against Celibacy," as its cover story. The New Yorker’s Hendrik Hertzberg, writing on April 1, expressed the deep suspicion about celibacy that is common these days: "Divorced from its spiritual purpose and turned into a job requirement, celibacy becomes either a sham or a suppression of one’s humanity, or both." How did Catholic conservatives respond? After a month of serious confusion and demoralization, they largely followed the lead of the Vatican’s chief press spokesman and embraced an argument that homosexuals in the priesthood are at the root of the crisis. Boston Herald columnist Joe Fitzgerald led the charge. "The old debate axiom holds that he who frames the question wins the issue, which is why militant homosexuals and their timorous allies in the politically correct movement are hell-bent on perpetuating the disingenuous notion that the crisis engulfing the Catholic Church has its roots in pedophilia," he wrote in a March column on the subculture of gay priests. "It does not. It has its roots in homosexuality." If nothing else, clear battle lines are now drawn. • Concern about zealous legal tactics. Law and other Catholic bishops, notably Cardinal Edward Egan in New York and Bishop Anthony Pila of Cleveland, apparently used such tactics to keep the lawsuits of sexual assault victims secret and to minimize diocesan liability to large settlements for damages. Both the Hartford Courant and the Cleveland Plain Dealer produced major investigative stories on the aggressive legal tactics adopted by bishops and their lawyers. The Courant relied on its own cache of diocesan documents collected in the legal process of discovery in suits filed against the Diocese of Bridgeport, Connecticut, and the Plain Dealer on the complaints of plaintiff’s lawyers for its March 10 story headlined "Diocese Uses Tough Tactics in Sex Suits. Facing Steep Liability, Church Plays ‘Hardball’ With Accusers, Critics Say." Among the complaints: combative depositions, using confidentiality agreements to prevent victims from testifying on behalf of other victims, and use of "boilerplate" legal defenses that priests are independent contractors of the diocese, not employees, or that the victim shared responsibility for any sexual abuse that occurred. An editorial, "Cardinal Egan’s State of Denial," in the March 27 Courant laid down the prevailing bottom-line demands from media and prosecutors. When charges of sexual abuse of children are involved the Catholic church must be regarded as an institution like any other. Alleged perpetrators must be reported to the authorities and must be kept permanently away from children, never readmitted to active ministry in any form. "For too long, the Catholic hierarchy rejected victims’ complaints, transferred priests to avoid embarrassment and did everything possible to coverup—even if that meant breaking the law by not reporting suspected abuse to prosecutors. That culture is changing, but not fast enough." As Easter approached, the number of Catholic bishops making statements about sexual misconduct grew. Many of them used the "Chrism Mass"—an annual event a few days before Easter that gathers the diocesan clergy to renew their priestly vows—to issue statements. Virtually all the bishops apologized for the misconduct of priests and promised to work hard to eliminate the problem. There again, responses varied. Many including New York’s Egan, Archbishop Daniel Cronin in Hartford, and Archbishop Daniel Pilarczyk in Cincinnati, focused on the sins of pedophile priests. But they stopped short of acknowledging that the current crisis was about their own behavior as administrators. This approach was epitomized by Cardinal Adam Maida’s comment carried in the March 25 Detroit Free Press: "I apologize for their mistakes." Others moved a bit further. Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua announced a diocesan "day of atonement and sanctification" for all of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia’s priests on April 24. Bishop Thomas Daily of Brooklyn—who dealt with the Geoghan matters as an official of the Archdiocese of Boston and who now faced newspaper stories that say he failed to address complaints of clergy misconduct in Brooklyn and Queens—included a brief but explicit apology during his Chrism Mass for his own failure to act. In Los Angeles, Cardinal Roger Mahony conducted a "Mass of reparations." The Los Angeles Times reported on March 26 that Mahony told reporters that he "accepts full responsibility as head of the nation’s largest archdiocese for the sins of the past. ‘I offer my sincere apologies,’" he declared, and went on to say that he would not hold victims of sexual abuse to the confidentiality agreements the archdiocese had required them to sign when lawsuits were settled. In Western Pennsylvania, Bishop Anthony Bosco of Greensburg said his diocese had to face up to the scandal. "The media and our people will not permit us to ignore or deny, nor should we," he said. "Denial is dishonesty." But the issue was addressed most directly by Bishop Robert Lynch of St. Petersburg—a man who, it was revealed, had recently settled a civil complaint that he had sexually harassed his own director of communications in the diocese—a charge he discussed openly with reporters. "The anger and disappointment of the church at this moment is not directed at you, my brother priests," Lynch was quoted by the Tampa Tribune on March 27. "It is directed at those of us called to lead at the episcopal level who are perceived by today’s standards as having covered up, hushed up, paid off, and continued to place children at risk." Lynch then underlined the point: "Only some form of communal acknowledgement of the error of the previous approach and an institutional apology to both victims and their parents and to the whole church can start a long overdue healing process." How far the "full disclosure" approach will spread remained to be seen. It was clear, however, that the public pressure to adopt "zero tolerance" policies is enormous: Boston, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles fell into place almost immediately after the scandal broke. Unlike matters such as priestly celibacy, American bishops do have the authority to frame their own diocesan policies and to take personal responsibility. But bishops who try to preserve a large measure of hierarchical discretion in the handling of misconduct cases and to insist on secrecy will face the question: "If other bishops follow a policy of mandatory reporting of allegations to criminal authorities, name names, and give numbers, why can’t you?" At Easter, attention was also turning in anticipation to the June meeting of the bishops’ conference, which was slated to discuss the crisis. As of this writing, it wasn’t known how much of the bishops’ discussion about the scandal would be public. Meetings of the conference typically include both public debate and closed-door sessions. But the bishops had best be prepared for the highest possible level of media attention and public scrutiny. Meanwhile, in the torrent of coverage, there were stories that suggested both how much things had changed because of the long scandal and that the Catholic church was likely to pass through this trial and to remain a very large, very strong religious institution that looks, acts, and operates much as it has. The Boston Globe sent reporter Tatsha Robertson to Dallas, where an early 1990s scandal focused on the Rev. Rudolph Kos eventually involved 11 plaintiffs and settlements totaling $31 million. Kos is now serving a life sentence and one of his victims committed suicide in 1992. Robertson’s report, headlined "Renewal of Faith: Roiled by Abuse, Dallas Diocese Recovered by Reaching Out," appeared on March 19. All Saints Church, where Kos served as pastor, now "boasts a record number of parishioners and is building another school. The Diocese of Dallas, which had to mortgage and sell property to pay the sex-abuse settlement awarded in 1997, has made a comeback, too. By 2000, all financial debts incurred had been repaid in full. Collection plates that went unfilled after the scandal have been overflowing of late." Priests across the diocese have been forbidden from being alone with children and church policies now mandate that volunteers, deacons, lay ministers, youth ministers, teachers, and priests be fingerprinted and subjected to criminal background checks." On March 26, USA Today reported that the "Santa Fe Archdiocese Learned Lessons." The scandal that rocked the archdiocese there in the early 1990s "hovered for three years of public horrors and private humiliation—and nearly bankrupted the Archdiocese of Santa Fe." The New Mexico ordeal involved 187 lawsuits against dozens of priests and cost the archdiocese and its insurers an estimated $25 million. But, once again, since 1993, church membership is up sharply and "23 seminarians have made it through AIDS tests and police background checks" to replenish the priesthood. Since it seems likely that this story will run for a while, it is worth mentioning three obvious areas where coverage should be improved: • The Numbers. One of the most shocking and depressing aspects of the scandal is the sheer number of alleged crimes and accused priests. The Archdiocese of Boston settled with about 130 plaintiffs in the Geoghan case. Perhaps more than 90 priests serving over the past 40 years stand accused. Settlements in the Geoghan case may reach $100 million. The total cost of settlements nationwide may reach $1 billion. But no one has been able to develop reliable numbers or to put them in accurate context. Stories abound toting up the numbers of cases or accused priests in this diocese or that one. But there aren’t reliable statistics anywhere accessible on the total national number of priests accused of sexual misconduct with minors, or even about the number or percentage of pedophiles in the general population. Part of the problem is the highly variable response of Catholic dioceses about making public accusations and outcomes. A few have been forthcoming; many others have not and there is no central repository of data. In January and February, for example, under vast pressure, Boston eventually dribbled out the numbers and then names of those priests accused. Philadelphia gave a number for total accusations over the past 50 years, but not the names of accused priests. New York refused to give either number or names. The search for basic facts: number of cases, number of priests, total of settlements, total of convictions, totals removed from ministry, remains bewildering. And new "zero tolerance" policies in Boston, Los Angeles and Philadelphia produced a wave of removals. Perhaps as many as 30 priests currently holding active ministerial assignments had accusations on their records. • Nomenclature. Stories early in this cycle, like most of those published or broadcast over the previous 15 years, referred almost exclusively to "pedophile priests" and "child molestation," and focused on assaults on pre-pubescent children. To some degree, this grew from the case of Geoghan, who was on trial for molesting a 10 year-old boy. But as time went on, the discussion became more complex. By March, stories like a piece in the Globe by Michael Paulson and Thomas Farragher, "Priest Abuse Cases Focus on Adolescents," suddenly began to proliferate. "The vast majority of priests who sexually abuse minors choose adolescent boys—not young children as their targets," Paulson and Farragher reported. Reporters had discovered that psychiatrists don’t regard sexual relations with pre-pubescent children as manifestations of the same psychiatric disorder as sexual relations with adolescents. "Pedophilia Treatable, Not Curable, Condition Experts Say," Fay Flam reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer. Earlier reports tended to stress that Catholic bishops and their senior staffs consistently failed to act on scientific information given to them in the 1980s that pedophilia is incurable. But it is not clear how important the distinction between adolescents and pre-pubescent children will be in the public realm. • Expert Sources. The base of sources quoted by journalists has been strikingly narrow. So far, Jason Berry, Eugene Kennedy, and A.W. Richard Sipe have been consulted and quoted almost everywhere. They are plausible experts. As a freelancer Berry helped break the 1984 Louisiana scandal story and has written prolifically about it ever since. Kennedy, a former priest and psychology professor, is a widely respected interpreter of Catholic matters. Sipe, also a former priest, is a therapist and researcher who has treated many priests charged with abusing children. Trenchant critics of celibacy, they are also vigorous proponents of sweeping liberal reform in the Catholic Church. Their expertise is real, but they are deeply committed actors and journalists rarely gave readers or viewers any sense of their larger reform agendas. Among the designated defenders of celibacy, Jesuit psychiatrist James Gill and James Berlin of Johns Hopkins University Medical School are also much cited. Again, both are legitimate experts, but are also figures in the controversy. Gill has a complex relationship with the hierarchy and has been directly involved in the treatment of pedophile priests. Berlin has outstanding credentials, but virtually carries the imprimatur of the bishops’ conference. An interview with him is a key part of the package of responses to the problem put up on the USCCB website. Berlin’s relationship with the hierarchy has not been specified in most of the coverage that quotes him. It is not that they should not be quoted, but that views of more experts, and less directly involved experts, would be useful. After Easter, the story seemed to pick up speed. A newly released set of church documents, this time dealing with the Boston archdiocese’s handling of a priest named Paul R. Shanley, cast Law in an even worse light. Shanley not only had a long and well-known history of abusing adolescent boys, but had openly declared that sex between adults and children causes no psychic damage. Yet Law and his subordinates kept this from church authorities in California and New York, preferring to give Shanley a clean bill of health and keep him out of their hair in Boston. In 1997, Law wrote a letter to Cardinal John O’Connor of New York signing off on Shanley’s appointment as director of a Catholic guest house in the city, despite "some controversy" in the priest’s past. "If you decide to allow Father Shanley to accept this position," Law wrote, "I would not object." On April 12, Law faxed a letter to Boston priests blaming the Shanley situation on inadequate archdiocesan "record keeping." He also said that he would remain in office for "as long as God gives me the opportunity"—a phrase he reiterated a few days later after an unannounced trip to Rome. But no one in Boston was betting that the opportunity would be there for long. A new poll found that 65 percent of Boston area Catholics wanted his resignation. Petitions circulated de-manding it. On April 15, a few days after signaling a hands-off policy, the Vatican summoned all American cardinals to Rome. On April 16, the Vatican issued a statement saying that the purpose of the meeting would be to "examine problems created in the church in the United States by scandals connected to pedophilia and to indicate guidelines meant to restore security and serenity to the families and trust to the clergy and the faithful." In Washington, Cardinal Theodore McCarrick suggested that both a national policy on sexual misconduct and more openness about the administrative errors of the past were necessary. "We have to make sure that we’re all on the same page and that every credible allegation gets to both the diocese and to the civil authorities," McCarrick told the Washington Post on April 17. "If the Holy Father says, ‘I think everybody should do this, then we all tend to do it.’" |