|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links:

From the Editor: The Word from Kampala’s Anglicans |

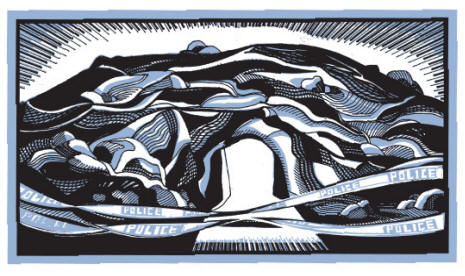

Death in the Sweat

Lodge

Even in a state that boasts the Grand Canyon and Monument Valley, the Red Rocks of Sedona inspire awe. Formed 350 million years ago, Arizona’s iron-rich sandstone formations are sacred to the Yavapai and Apache even as they draw New Agers in search of healing vortexes of spiritual energy. On August 16, 1987, thousands of the latter gathered there for the Harmonic Conversion to welcome a new era of peace and love. But 22 years later, on October 8, the Red Rocks presided over neither healing nor harmony. During a version of a Native American sweat lodge ceremony run by best-selling author James Arthur Ray, two participants died on the scene, and 20 others were sent to local hospitals. A third person died from multiple organ failure after lying in a coma for nine days. Just as the Red Rocks mean different things for New Agers and Native Americans, coverage of the deaths and their aftermath spun out in two directions. For the mainstream media, the deaths sparked an overdue look at Ray’s self-help empire and the $11 billion personal development industry. In the Native American media, the story was almost exclusively outrage over the hijacking of their spiritual heritage. The first hint that something had gone wrong came in a 911 call, the audio of which would be played in an endless loop on TV programs from the tragedy-magnet Nancy Grace Show to the networks’ nightly news:

Jon Hutchinson, staff reporter for the Verde Independent, filed one of the early local stories the next day. Details were sketchy, but, Hutchinson reported, the sweat lodge had been the final event of James Ray’s Spiritual Warrior Retreat; 48 participants “had paid over $9000 for the experience.” He added that over 60 people may have been in a shoulder-high domed structure. Fire Spokeswoman Barbara Rice noted that crews found “a lack of oxygen between the coverings,” which included plastic tarps. In the newspaper world, Phoenix-based AP reporter Felicia Fonseca became the go-to journalist on the Sweat Lodge deaths and their aftermath, writing over 25 (and counting) articles. Her first piece (“Authorities seek cause of Arizona sweat lodge deaths”) was filed at 7:30 a.m. on October 9 and reprinted in major newspapers from the New York Times to the Dallas Morning News. Fonseca immediately focused on one salient point: While sweat lodges have been safely used by Native Americans (and other cultures) for centuries, this particular lodge was too crowded, too hot, lasted too long, and used non-breathing plastic tarps (instead of animal skins and blankets) as coverings. She quoted a warning by author Joseph Bruchac (The Native American Sweat Lodge: History and Legends): “When you imitate someone’s tradition and you don’t know what you are doing, there’s a danger of doing something very wrong.” Fonseca was also the first to note that Ray, who left the state shortly after the deadly event, preferred to stay in touch via his website, Facebook page, and Twitter account. In fact, Fonseca reported in an October 10 article, Ray actually tweeted his expression of sympathy to survivors and families of the deceased—in the required 140 characters or less: “My deep heartfelt condolences to family and friends of those who lost their lives. I am spending the weekend in prayer and meditation for all involved in this difficult time; and I ask you to join me in doing the same.” Also pouncing on Ray’s unfortunate tweets were Erin Calabrese and Lukas I. Alpert in a scathing October 11 article in the New York Post: “During his Spiritual Warrior retreat, James Arthur Ray, 51, had twittered: ‘For anything new to live, something first must die. What needs to die in you so that new life can emerge?’” This seemingly ominous tweet would be reprinted in many articles and broadcasts, long after Ray unsuccessfully tried to delete it from his account’s archives. Felicia Fonseca relentlessly gathered facts and filed an impressive series of articles on the developing story. On October 14, she gave details of the strenuous days leading up to the sweat lodge, including a risky 36-hour solo fast in the desert that only ended the morning of the sweat. Later that same day, she filed a story that followed Ray to Los Angeles, where he broke down in tears during a public lecture and, taking a cue from O. J. Simpson, announced that he was hiring his own team of investigators to “uncover the truth.” The next day, she covered the announcement by Yavapai County Sheriff Steve Waugh that the deaths were being treated as homicides, and that Ray was the “primary focus of the investigation.” The death of third victim Liz Neuman was the focus of Fonseca’s October 18 story, which revealed that the Neuman family had plans to sue Ray. Later that day, Ray updated his Facebook status to say he was “saddened by the news of Neuman’s death.” Ray would find more opportunities for distress in the weeks and months to come. On October 21, Fonseca wrote a devastating article drawing on the first account given by eyewitness Beverly Bunn, an orthodontist from Texas, who told of multiple people vomiting and collapsing during the oppressively hot ceremony. Bunn related that Ray stood by the door and urged people not to leave in between the 15-minute rounds when the flap was closed. When Bunn heard voices yelling that a woman had passed out, Ray replied, “We will deal will that after the next round.” And on February 3, Fonseca reported that Ray had been arrested and taken into custody on three counts of manslaughter, his bail set at $5 million. While his lawyers stressed that there had been no criminal intent, the mother of victim Kirby Brown disagreed: “This wasn’t just a horrible accident. His own conviction in his omnipotence and his own seduction of money and wealth made him delusional.” Ray had to stay in jail for a month until his bail was reduced. Having cancelled all of his public appearances (and been told by the judge not to conduct any sweat lodge ceremonies), Ray took to his video blog and Twitter account to protest his innocence and spread his gospel of Harmonic Wealth. While Fonseca did most of the heavy lifting in the daily newsgathering, other journalists took on the enigma of James Arthur Ray. Craig Harris and Dennis Wagner wrote an in-depth profile in the October 23 Arizona Republic that told the rags-to-riches rise of the son of an Oklahoma preacher, who “even as a boy…was fixated on money and spirituality.” As an example, the article quotes from Ray’s 2008 book Harmonic Wealth, where he describes getting a revelation as a boy while listening to his father preach in Tulsa’s Red Fork Church of God: “I hear the words that would play in the background of my life like annoying elevator music for years to come: ‘It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven.’ That cannot be true, I thought.” The article described Ray’s short stint in junior college, his years as a sales manager for ATT, bankruptcy and depression—all leading to a 10-day trek through the Sinai Desert, where he said he had the inspiration for the principle of Harmonic Wealth–how to attain riches, health, and peace of mind through what Harris and Wagner call “a cobbling of religions, ancient mysticism, modern science and far-flung philosophies.” According to Kate Linthicum and DeeDee Correll of the Los Angeles Times, Ray’s success came after his inclusion as one of the expert talking heads in The Secret, a wildly popular 2007 documentary that has sold over 4 million copies. The brainchild of Australian TV producer Rhonda Byrne, it purports to divulge the ancient “Law of Attraction”: If you visualize wealth, health, or happiness, a thinking universe will send it back to you. While the DVD claims “the secret” has been suppressed since ancient times, Byrne told Jerry Adler in the March 21, 2007 Newsweek that her inspiration was the 1910 book The Science of Getting Rich by Wallace D. Wattles. Adler wrote that Wattles was a member of the New Thought movement, described by Rutgers historian Beryl Satter as “a self-help movement that drew on 19th-century Americans’ suspicion of elites and on the Protestant tradition of looking for the ‘inner light.’” When The Secret hit it big, James Ray reached a wide TV audience after appearing in 2007 on Larry King Live, Today, The Ellen DeGeneres Show, and Oprah—twice. While none of the TV hosts asked hard questions, Winfrey positively gushed in her praise, even appearing on Larry King Live June 28, 2007 to praise The Secret’s philosophy. “You really can change your own reality based on the way you think,” she claimed. By September 2009, James Ray was a well-known, mainstream leader in the New Age movement. His company, James Ray International, had revenues of close to ten million dollars, over 14,000 people had attended his lectures, seminars and retreats, and he lived in a $4 million mansion in Beverly Hills. But trouble had disturbed his paradise before the events of October 8. This time, it was the New York Post’s Jeane Macintosh who revealed some secrets, reporting that earlier Ray seminars “were already tainted by serious injury and even suicide.” She described an event at Disney World in 2005 when a New Jersey woman broke her hand after Ray “bullied her into performing a ritualistic board-breaking exercise.” Worse, in July of 2009, when Ray dropped off a group on the streets of San Diego in rags and without IDs or money to see what it was like to be homeless, one of the participants, Colleen Conaway, jumped to her death from a mall. As revelations continued about Ray’s past mistakes and his actions during the fatal sweat ceremony, a small but growing number of journalists began to question the safety for “consumers” of New Age practices. “The deaths… have led critics of the self-help industry to step up their attacks,” Scott Kraft reported in an October 22 article in the Los Angeles Times. Kraft quoted John Curtis, founder of the website Americans Against Self-Help Fraud (AASH), about his claim that charismatic leaders like Ray prey on confused people to make money. “I’m hoping and praying that this will put a chilling effect on the self-help industry,” Curtis related. On his own website, Curtis’s February 1 posting was more passionate. “What does the terrorist’s failed attempt to blow up a jetliner have in common with James Ray’s Sweat Lodge Deaths? While President Obama proposed looking at airline security and enacting regulations to protect Americans’ lives… a 11 billion dollar industry is “completely unregulated,” with “NO national organization, NO code of conduct, NO credentials, NO ethical standards, NO means to sanction, NO spokesperson…. (etc.)." In more measured tones, Steve Salerno penned a feature in the Wall Street Journal October 23 warning that the industry “can hurt you psychically, it can hurt you financially, and, as we see, it can hurt you physically.” The worst part, for Salerno, was that “these activities…once seen as fringe stuff back in the mid-70s…have gone mainstream.” He concluded that while self-help books fight with Harry Potter for dominance on the best seller lists, “At least most people realize that Harry Potter’s wizardry is fictional.” Christine Whelan, professor of sociology at the University of Iowa, wrote a more sympathetic piece in the October 25 Washington Post that got at the appeal of a James Ray. “What would you do for spiritual enlightenment and personal success?” She asked,” Would you follow a trusted leader into a dark, hot tent to experience a version of a centuries-old Native American sweat lodge ritual?” The answer? “History shows that in the name of self-help, many people will do just that—and more.” What raised red flags for Whelan were both Ray’s recklessness and his followers’ bad judgment, especially when it came to “the lack of emergency back-up, the intensity of the heat, and not monitoring participants during the sweat, which all led to negligent behavior that is disturbing.” So, is it simply up to the participants to make sure their experiences are safe? Or, as proposed by U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) of in a letter to Attorney General Eric Holder, should there be a federal investigation of the October 8 incident and a closer look by the Justice Department and the FTC into similar activities offered by different companies? As the mainstream media tried to assign blame to the shadier corners of the New Age, outrage among Native Americans over the sweat lodge deaths—and the commercialization of their ancient ceremony—was visceral. While local issues of zoning and education preoccupy most of the over 160 newspapers, journals, and online news sites serving the U.S. Native population, this story reverberated far beyond Arizona. The Navaho-Hopi Observer ran a typically angry op-ed October 20 by Chief Avrol Looking Horse of the Lakota/Dakota/Nakota Nation, who wrote, “[O]ur way of life is now being exploited and you do more damage than good. No mention of monetary energy should exist in healing.” Indian Country Today, a weekly newspaper and website based in New York that is the biggest distributor of Indian news in the country, ran a news article announcing that Idaho’s Couer d’Alene tribal council had passed a resolution condemning “these types of activities by non-Natives.” Explaining the lodges’ vital importance in helping Native veterans and troubled young people, it expressed the nearly universal opinion that “across the country Native Americans are very appalled by what they read.” On October 29, the Native Unity Digest website ran an opinion piece by Bahe Rock, a member of the Diné people, who demanded that Native ceremonies “must be covered under the guidelines that were developed to recover stolen ancient artifacts. As ever, native people must be vigilant about our human rights…and the protection of our existence.” On November 1, Sam Longblackcat filed a lawsuit on behalf of the Lakota Nation (located in North and South Dakota) against the U.S. Government, Arizona, James Arthur Ray, and the Angel Valley Retreat Center, stating that allowing non-Native ceremonies close to the sacred Red Rocks violates the terms of their 1868 Peace Treaty. “After all,” Longblackcat wrote of Ray’s sweat lodge tragedy, “We don’t go into a Roman Catholic church, put on the Pope’s hat and take the Pope’s staff and call ourselves Pope.” On January 20, Arizona state senator Albert Hale, a former president of the Navaho Nation, introduced Bill 1164, which would require the Arizona Department of Health Services to regulate non-Native American individuals or businesses that charge people for taking part in traditional ceremonies. Citing the incident in Sedona, Hale told the Arizona Daily Star, “The dominant society has taken all that we have: our land, our water, our language. Now they’re trying to take our way of life, and I think it has to stop at some point.” In spite of the three deaths, it is doubtful that Anglo seekers of enlightenment will desist in exploring Native American spirituality. After all, Americans are known for appropriating whatever they like about different religions (yoga, meditation, angels, kabbalah) and ditching what they don’t. Sedona’s Red Rocks will continue—for different reasons—to be a focus for alternative spiritual seekers and questionable New Age leaders as well as for Native Americans. There is, however, a need for journalists—and especially religion writers—to investigate the practices, beliefs and personal empires of the booming, and completely mainstream, New Age phenomenon. James Ray’s court date of August 31 was postponed after his defense team requested a change of venue. If convicted, he could spend 12-and-a-half years behind bars for each manslaughter charge. Media interest will re-emerge as the trial nears—in fact, on June 12, NBC’s Dateline devoted an entire sensationalized hour to the story that added little insight to what was already known. Meanwhile, with his spiritual empire in shambles and his future uncertain, Ray continues to send out tweets and blog posts, albeit backpedalling from his usual positive message. “Sometimes we fall into the romantic mindset that if I read the right book or I study with the right teacher or I learn the Law of Attraction or whatever it is, the laws of the universe, that I’m not going to have any more challenges or obstacles in my life,” he says on a July 6 video entry. “And yet deep down inside, I think all of us know that’s just not true.” |