|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links: Articles in this issue:

From the Editor: Breaking Up Is Hard to Adjudicate |

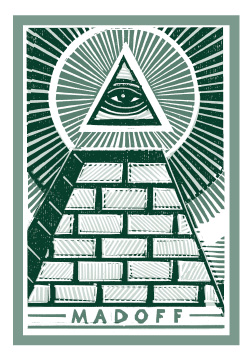

The Madoff Disgrace by Jerome Chanes

Developed elaborately, audaciously, unbelievably, over decades, the scheme swindled any number of prominent Jewish investors—movie director Steven Spielberg, New Jersey Senator Frank Lautenberg, publishing and real-estate poobah Mort Zuckerman, Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel, baseball exec Fred Wilpon, to name a few. Then there were important institutions of the Jewish community, including the American Jewish Congress and Yeshiva University, each of which lost in the neighborhood of $100 million. The swindle likewise devastated a sizable number of charitable and social service organizations as well as some 160 private foundations, most of them Jewish-owned and involved in Jewish communal giving. After the initial shock of the Madoff revelations and his arrest December 11, editors of Jewish newspapers came to a collective decision, albeit independently of one another: Coverage would focus on the damage done to Jewish institutions. For the Jewish press and its regnant news service, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA), the heart of the story was how Madoff had damaged the Jewish organizational world and, by extension, the entire Jewish communal structure in America and abroad. “Any time we got any info on any damage, we reported it immediately,” Ami Eden, the editor-in-chief of the JTA told me April 30. “People want to have the news when the sky is falling.” The Forward, an independent weekly often cited as the Jewish newspaper of record, led its December 12 issue—the day after Madoff’s arrest—with “Madoff Arrest Sends Shock-Waves through Jewish Philanthropy.” Reporters Gabrielle Birkner and Anthony Weiss traced Yeshiva University’s losses, then moved through a range of Jewish philanthropic, social service, and educational agencies. Together with JTA and the larger local weeklies, the Forward set the pattern for subsequent Madoff stories in the dozens of local community newspapers serving the vast majority of American Jews. Typical of the coverage were the two stories in the December 18 issue of the New Jersey Jewish News that ran under the headline, “Madoff Scandal Rocks Jewish Fund-Raising World,” which identified local and national charities and foundations that were taking hits. Jewish newspapers abroad focused on Jewish communal damage as well. The Jerusalem Post headlined its December 15 story, “$600 Million in Jewish Charitable Funds Lost,” following up December 18 with a report on the disastrous loss, estimated at $90 million, to Hadassah, the women’s Zionist organization that is the largest Jewish membership organization in the United States. On December 24, Haaretz, the daily often characterized as the New York Times of Israel, reported that the American fundraising arm of the Israel Institute of Technology (Technion) had lost $72 million. Not that the general media ignored this aspect of the story. As the Los Angeles Times December 16 headline put it: “Madoff Debacle Hits Region’s Jewish Community.” Interestingly, the only article offering a full discussion of the highly sensitive issue of Jewish education appeared not in the Jewish press but in an article by Nicole Neroualis for the Religion News Service January 9 (“After Madoff, Jewish Yeshivas Say they Can’t ‘Go it Alone,’”). Neroualis focused on the 800 mostly Orthodox day schools, and their need to press synagogue congregants for more support. What distinguished coverage in the “secular” press was its attention to Bernard Madoff’s Jewishness—how that was key to understanding the scandal. From its vantage at Jewish America’s ground zero, the New York Times placed the subject front and center in no fewer than six stories. On December 28, Robin Pogrebin was the first to explore it in a story headlined, “In Madoff Scandal, Jews Feel an Acute Betrayal.” In a lighter vein, there was Patricia Cohen’s January 17 story, “But is Madoff Not So Good for the Jews? Discuss Among Yourselves,” reporting on a panel discussion (“Madoff: A Jewish Reckoning”) convened by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in Manhattan that featured Jewish academics Simon Schama and Michael Walzer and Wall Street powerbrokers Mort Zuckerman, Michael Steinhardt, and William Ackman. Indeed, Madoff’s crime was fundamentally about his ability to meet, cultivate, and work with wealthy Jews—above all in the Jewish social scene in Palm Beach, Florida. His was, in other words, a classic “affinity” crime. In contrast to Enron CFO Andrew Fastow, for example, whose Jewishness was irrelevant to the story of the collapse and disgrace of that corporate giant, Madoff’s Jewishness mattered. Jews trusted Bernard Madoff as one of their own. How could such a man bring harm to their community? But if Madoff’s Jewishness played a central role in his criminal activity—and was publicly discussed among Jews—it was not emphasized in the Jewish press. Editors felt that there was sufficient coverage of this issue in the general press and also that it was a given. Madoff was the Jew who preyed on Jews. His villainy and deviltry had to do with the theft of Jewish dollars, especially Jewish charitable dollars. At bottom, for the Jewish press, the story was the damage. A number of thoughtful opinion pieces appeared in the early weeks of the story. One, by Brandeis historian Jonathan Sarna in the February 26 issue of the Los Angeles Jewish Journal, placed the impact of the Madoff affair in the context of previous crashes, calling special attention to the strain on Jewish education and the reduction of support for the communal needs of Jews abroad. Sarna correctly identified the most affected portion of the Jewish community: “Orthodox Jews have been disproportionately involved in banking and in the stock market, and were also disproportionately hurt by Madoff. They are also heavy users of our most expensive Jewish institutions (synagogues and schools).” Toting up the loss of billions of dollars in and to Jewish endowments, the hits taken by Jewish organizations, and the spill-over in terms of fundraising, he pointedly concluded, “Nobody has put forth serious ideas about how to cut the Jewish communal budget by one-third. That, however, might well be what we need to do.” In a column in the March issue of the Philadelphia Jewish Voice, publisher Daniel E. Loeb focused on the “tzedakah” (charity) angle, noting that Madoff’s “charitable work gave him the credibility and the financial connections to guarantee a net flow of cash into his hedge fund for almost five decades.” Loeb criticized the lack of due diligence and proper vetting on the part of Jewish institutions of proposed investments and investment agents. More controversially, New York Times Magazine contributing editor Daphne Merkin weighed in March 22 with a column suggesting that the victim’s of Madoff’s evil were, in effect, willing collaborators in crime. “[T]heirs was a voluntary—nay, eager—association,” Merkin wrote. “In a way Mr. Madoff and those he defrauded were co-dependent, the one offering a cover of benign paternalism and the other buying into the act.” Merkin’s opinion piece was reflective neither of the general tone nor of the substance of media coverage of Madoff. But what she was saying was, at some level, true; Merkin was walking down the “affinity crime” path charted by some of the coverage—but she was nonetheless attacked by many in the Jewish community for her characterizations, which smacked of Hannah Arendt’s readiness to consider Jews complicitous in the Holocaust. One of those who certainly bought into the act was Merkin’s brother, J. Ezra Merkin, who reported early on that his hedge fund, Ascot Partners, had been defrauded by Madoff. That was true enough, so far as it went. But Ezra Merkin reportedly had long been the go-between for Madoff and a number of Jewish institutions, and served as an investment adviser for them. Prominent among these were Yeshiva University; State of Israel Bonds; Ramaz School and SAR Academy, important Orthodox day schools in New York; New York’s Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun, one of the leading Orthodox synagogues in the country; and—not least—New York’s Fifth Avenue Synagogue, which Merkin served as president. Reportedly, Ezra Merkin took a fee for moving Yeshiva’s money to Madoff. But, according to sources, many institutions and individuals simply had money in Ascot, and lost it because of Merkin’s own decision to invest heavily with Madoff. To paraphrase the old Watergate question, “What did Merkin know and when did he know it?” The answer is not yet clear. Ezra Merkin’s involvement with Madoff was covered extensively in the Jewish media—indeed the Jewish press was ahead of the curve on the story—because it pointed up the sense of betrayal that pervaded the case. “They stole tzedakah money,” JTA’s editor told me. “And this is what the ‘Jewish crime’ was all about, and this is what we covered.” Among the fears most foul expressed by some American Jews, professional and lay, was that the affair would trigger expressions of antisemitism. Madoff’s lavish lifestyle was widely reported. Would the outside world stereotype him as the Predatory Jew? A few pieces of evidence made their way into print. The Jerusalem Post, known for its rightward tilt in recent years, reported on what it found in cyberspace in a December 20 story, “Madoff Scam Spurs Online Anti-Semitism.” Similarly, on December 26 the Raleigh News and Observer ran a story on an Anti-Defamation League (ADL) report of a spike in antisemitic comments online following Madoff’s arrest. But the Jewish press paid little attention, simply because there was so little to report. In this regard, the Madoff story followed a well-established pattern in American Jewish life. The Rosenberg atomic spy case in the 1950s; the gas price crisis of the 1970s, with its Middle East connection; the Boesky financial scandal of the 1980s; the farm crisis that devastated the Plains states during the 1980s; and, most dramatically, the Jonathan Pollard spy case, which directly raised the question of dual loyalty—there was widespread expectation that antisemitism would result from each one of these highly-polarizing situations, and none did. So with Madoff. In 2008-2009, the economic meltdown was so immense, with so many causes—to say nothing of the fact that this was perceived as a “Jew-on-Jew” crime—that Main Street did not say, “The economy is going to hell because of the Jew Madoff.” Moreover, precisely because Jewishness was intrinsic to the story, antisemitism was less likely to be a matter of concern. Editors understood the dynamic. “If Jewishness has nothing to do with a story, and somebody raises Jewishness, then—hey!—it’s anti-Semitism,” an editor of one of the larger papers observed to me. “But here, where Jewishness is what the story is all about, it’s hard to find scapegoating of Jews.” This sentiment was reflected in “Concern about Anti-Semitism,” the New York Jewish Week’s December 23 editorial: “The concern is appropriate. But it should be tempered with some perspective: this is not the America of 1932, when the Great Depression produced an anti-Semitism that was not confined to the nation’s marginal fringes.” Indeed, the editorial chided the American Jewish Committee for its criticism of the New York Times for being “over the top” in emphasizing Jewish connections to the Madoff scandal: “[N]ews coverage of the connection between Madoff and both his Jewish enablers and victims has generally been sensitive and fair.” Again, the Jewish Week got it right—and led the way on Jewish coverage of this issue. But even though worries about antisemitism were quickly laid to rest, there remained concern for about how the affair was perceived by non-Jews. As one Jewish communal official said to me, “I very rarely have the reaction of ‘a shande fahr di Goyim’ [a shameful display before non-Jews]. The Madoff affair was one of those very rare times.” This visceral feeling may have been widespread, but it was almost completely unreported. But the bottom line in the Bernard Madoff story was not, for the Jewish community, “What will they think of us?” but “What does it say about us? How do we go about doing our business? What does it mean for Jewish life in America in the 21st century?” In this respect, the Jewish papers did their job, and did their job well. The question of how and why the Jewish press covered the Madoff story differently from the general press is not only about institutional and organizational concerns, as central as those were as reports of the damage came in after December 11. It has everything to do with feelings of Jewish security. The American Jewish community is very different today than a half-century ago, when it still felt insecure, defensive, exposed. Did the relatively new sense of security tremble in the Jewish coverage of Madoff? Did some of the old insecurity come out? It did not, and this was the Madoff story. The impact of the Madoff crimes on the American Jewish community was both broad and deep. As a practical matter, Jewish groups immediately began looking inward, to their budgets, to their fund-raising mechanisms, to their investment strategies and investors, to their charitable allocations, to their communal planning, to their organizational structures. “What do we do now?” and “What do we need to do to prevent this from happening again?” were the salient questions. But the impact went far deeper than institutional reactions. Even Jews who did not have the “shande fahr di Goyim” reaction felt abused by Madoff. The issue was not that Bernard Madoff had bilked Jewish investors—and some non-Jewish ones—out of $50 billion. It was that he had stolen directly, knowingly, and uncaringly from Jewish communal charity. Jews were enraged by his cynical use of his Jewishness to bilk Jewish communal funds. It was the worst kind of betrayal. |