|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links: Articles in this issue: From the Editor: |

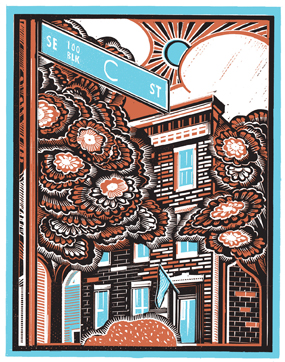

Sanford

and Wife

First came married Nevada senator John Ensign’s June 16 confession of an affair with his onetime campaign treasurer, Cynthia Hampton, wife of his co-chief of staff and best friend Doug Hampton. The high jinks of this scandal had observers excited for days. Titillating as they were, Ensign’s problems all but vanished on June 24, when married South Carolina governor Mark Sanford tearfully admitted to the world that rather than hiking the Appalachian Trail as he had told his staff, he had secretly been visiting a paramour in Argentina. In his 18-minute speech in the state capitol in Columbia, Sanford made clear that he had cheated on his wife Jenny, deserted his four sons over Father’s Day weekend, and left the state of South Carolina with nobody in charge and no one knowing how to contact him. Later that day, the Columbia State, which owned the Sanford story, published emails between Sanford and the Argentinean woman identified as “Maria,” displaying to the world the governor’s turgid attempts at erotic prose and wistful paeans to an “impossible love.” He was, riffed Jon Stewart, “another politician with a conservative mind and a liberal penis.” Next day, the Wall Street Journal quoted Katon Dawson, a former South Carolina GOP chair, as calling the governor’s disappearance and subsequent explanation “the damnedest thing I’d ever seen.” The paper noted that, as a member of the House of Representatives, Sanford had voted to impeach Bill Clinton because, he said, of the need to restore moral legitimacy. Meanwhile, Dan Balz of the Washington Post wrote that Sanford’s scandal “further damages the GOP brand” and that it “could disillusion social and religious conservatives.” As sometime GOP operative Matthew Dowd ruefully noted, “If Republicans talk about family values, people will roll their eyes.” Even Jeffrey Kuhner in the conservative Washington Times, citing Ensign affair as well as senators Larry Craig and David Vitter and representative Mark Foley, pointed out that Sanford was “only one in a long line of Republican politicians who, while sounding like preachers and priests, have behaved like perverts and pimps.” In his June 27 article, Kuhner let them have it: “The American right is permeated with sanctimonious hypocrites who talk like traditionalists but live like libertines.” Sanford tried to nip this talk in the bud first by presenting himself as a good Christian man who had tried to live a righteous life but was a sinner no less than any other man. During his confessional press conference, Sanford praised one Warren “Cubby” Culbertson, present in the room, as a “spiritual giant” and “an incredibly dear friend” who had been helping Sanford and his wife “work through this over these last five months.” (Meredith Simons of Slate jumped immediately on this lead, publishing a short piece about Culbertson’s Round Table, a men’s Bible study group in Columbia that Sanford had briefly attended.) More aggressively, Sanford also invoked the biblical King David (who committed adultery with Bathsheba and then contrived the death of her husband) to explain why he should not have to resign and why the people of South Carolina ought to forgive him. In a televised meeting with his cabinet on June 26, Sanford said, “What I find interesting is the story of David, and that the way in which he fell mightily, fell in very, very significant ways, but then picked up the pieces and built from there.” Most reporters seemed baffled by the David comparison, but in a July 1 interview on NPR’s Fresh Air, author Jeff Sharlet noted that it was a common trope employed by The Family, an elitist religious group in Washington that Sanford had frequented. Why would Sanford invoke King David to save his own career, asked Sharlet (whose book on The Family appeared in 2008) “Because God chose him. King David is beyond morality in their limited understanding of Scripture, and that’s a central parable in The Family’s thinking.” The affair showed him to be an ordinary sinner, Sanford seemed to be saying, but no less chosen for being human. Also known as The Fellowship and nicknamed “C Street” for the location of its residence near the Capitol, The Family turned out to have played a significant role in John Ensign’s life and affair as well. Secretive but, thanks to Sharlet, newly revealed for global political machinations and a masculinist worldview, the organization had provided a refuge, counseling, and apparent oversight of Ensign’s affair as well as significant nurturing of Sanford during his congressional years and likely promotion of his presidential aspirations. The extent of The Family’s involvement in Sanford’s life is still unclear, but it is worth noting Sharlet’s July 14 statement on the Religion Dispatches website about its preoccupation with “male authority…a purified straight identity, a manhood purged of anything feminine.” (This was, incidentally, a stronger assertion about the organization’s emphasis on gender than Sharlet promulgated anywhere in his book.) In fact, what the Sanford affair illuminates, above all, is the gender politics at the heart of conservative evangelicalism today. Not that this is something new. Conservative preacher John R. Rice’s 1941 best-seller Bobbed Hair, Bossy Wives, and Women Preachers was one in a long line of prescriptive texts aimed to keep women in submission to male authority. Billy Graham raised the specter of selfish career women countless times in his revival sermons, while latter-day evangelicals like James Dobson, Jerry Falwell, Beverly LaHaye, and Pat Robertson built their conservative empires by stoking fear of feminism and urging women (ironically in the case of LaHaye) to return full-time to hearth and home. Evangelicals have also attended to gender by encouraging specific forms of conservative male bonding and discipleship. Remember the Promise Keepers (PK)? Far from representing something new among evangelical men, as we were often told in the 1990s, PK was just the latest expression of male self-help present throughout evangelicalism’s history. PK flourished about the same time that Southern Baptists saw fit to urge Christian wives to “submit graciously to their husbands.” In this light, the relationship between Sanford and Cubby Culbertson, and with the all-male world of The Family, point to a religious worldview in which female submission to spiritually conditioned male authority matters deeply. The twist came when Jenny Sanford refused to play to script—and received accolades for her resistance from all sides. The story began when Jenny failed to show up at Sanford’s June 24 press conference, instead issuing her own strategically crafted statement shortly thereafter. In it, she let the public know that she had kicked her husband out of the house two weeks earlier. “We reached a point where I felt it was important to look my sons in the eyes and maintain my dignity, self-respect, and my basic sense of right and wrong,” she said. Nonetheless, she insisted that she believed in the sanctity of marriage and that, after having “put forth every possible effort to be the best wife during almost 20 years of marriage,” she was ready to forgive and stick it out for the sake of the children. At least, so long as her philandering man was truly humble and repentant. Newsweek’s Kathleen Deveny gave shape to the ensuing sympathetic media coverage of Jenny in “Scorned: A User’s Manual,” an online essay of June 25 in which she called Jenny Sanford a “media genius.” As Deveny saw it, Jenny Sanford “deftly transformed her public humiliation into a weapon—and beat her cheating husband about the head with it. While quoting Psalms!” Jenny had foregone the role reprised by the wives of adulterous politicians—the doormat moments of Hillary (Mrs. Bill) Clinton, Dina (Mrs. Jim) McGreevy, Suzanne (Mrs. Larry) Craig, Silda (Mrs. Eliot) Spitzer, Wendy (Mrs. David) Vitter, and Darlene (Mrs. John) Ensign. She would not play the dutiful, or rather, the pitiful wife, twice victimized by standing by her man during his public admission of having dishonored her. Instead, Deveny wrote, she left her husband to “hang himself—and look really dopey while doing it,” and thereby “somehow managed to come out of a god-awful mess with a little bit of dignity.” Suddenly, Jenny Sanford became a sort of feminist heroine: the Georgetown-educated, independently wealthy financial whiz who had met her husband when both were working on Wall Street and who, by running his successful political campaigns, made his entire career. Even as the death of Michael Jackson on June 25 shifted the spotlight away from the Sanfords, female reporters (especially) continued to follow the story of Jenny Sanford’s strength in adversity, her refusal to play the victim. She told the reporters staking out her vacation home on Sullivan’s Island that her husband’s career “is not a concern of mine. He’s going to have to worry about that. I’m worried about my family and the character of my children.” Increasingly, she was described as “tough” and “astute,” while Mark Sanford’s gesture of wiping away tears in public became an object of satire. (Fox News headline: “How do You Solve a Problem…LIKE MARIA?”). As the New York Times’ Leslie Kaufman pointed out on June 27, “For thousands of women, responding on the Internet and Twitter, Mrs. Sanford’s decision to hold her husband accountable provided a catharsis, a kind of public exorcism of the ghosts of political wives past.” On Slate.com, Emily Yoffe crowed, “Wasn’t it grand!” and praised Jenny’s perfect “passive aggressiveness” in letting her husband have it without sullying or humiliating herself. Jenny Sanford knew exactly how to work the gender angle of this story, and she continued to do it beautifully. In a June 26 interview, she told Bruce Smith of the AP how her cheating husband repeatedly asked permission to visit his lover in the months after she discovered his affair, and how she unequivocally refused. His secret rendezvous in June had “devastated” Jenny, she said, since “he was told in no uncertain terms not to see her.” “You would think that a father who didn’t have contact with his children, if he wanted those children, he would toe the line a little bit,” she said. At the close of this interview, Smith reported that Jenny wept—just enough grief to keep her from seeming cold. “On the coffee table was a collection of devotional books, including a book of commentary on the Bible’s Book of Job, the story of a man whose faith God tests to the extreme. ‘Parenting is the most important job there is, and what Mark has done has added a serious weight to that job,’ she said.” End of story. Here was Jenny Sanford as a perfect role model of family values and nurturing motherhood: Despite her Wall Street heritage, and even while serving as Sanford’s “top political adviser,” Jenny’s real career, as she presented it, was devoted motherhood to four handsome, well-tended sons. Warm but not obsequious, pretty without being threateningly beautiful, strong yet wounded by the man she loved, she seemed to be a woman that all women could adore and admire. Was it any surprise that indignation over her public shame swept the nation? Even as Jenny was receiving kudos from the secular media, she was lauded by conservative Christians. The online Church Leader Gazette praised her June 24 pro-marriage statement and focus on the character of her children, reprinting her statement under the headline, “South Carolina First Lady Jenny Sanford Shows Forth Love, Grace, and Strength in Her Statement After Her Husband’s Affair.” (Mark Sanford echoed the sentiment two days later: “I’d simply say that Jenny has been absolutely magnanimous and gracious as a wonderful Christian woman in this process.”) A Christian woman, indeed she was; but what kind? Little was made of it in the mainstream press, but Jenny is in fact not an evangelical but a Catholic, Chicago-born and raised. Catholics and evangelicals, once bitter political enemies, have famously united in recent decades on gender—or genital—issues (most importantly abortion and opposition to gay marriage), so in one sense her Catholicism can be considered no big deal. The ease with which even the evangelical media took her to be a “Christian,” unmodified and unqualified, tells us something about the atrophying of anti-Catholicism in the South. At the same time, observers might well ask why it took a Catholic woman, and one raised in a region other than the South, to subvert the script of standing by her man at all costs to preserve her marriage. Jenny’s resolute clarity in the face of her husband’s disgrace suggests an independence from the submissive wifehood enjoined even on professional women in evangelical circles. (Silda Wall Spitzer, it’s worth noting, was raised a Southern Baptist in North Carolina and was described during her husband’s short governorship as “a good Baptist.”) Did Jenny Sanford’s Catholicism make the difference? Whatever the answer, her dexterous handling of the media, secular and Christian alike testified to an instinct for self-preservation possibly capacious enough to salvage her husband’s career. Not that Mark Sanford made it easy. On July 1, the AP’s Tamara Lush poured two days of exclusive interviews with him into a tale of a Grand Passion. “This was a whole lot more than a simple affair,” Sanford told her. “This was a love story. A forbidden one, a tragic one, but a love story at the end of the day.” It was, Lush wrote, “bombshell after bombshell,” with Sanford admitting that he wasn’t in love with his wife and that he had had dalliances with other women: “‘Though we both know how impossible our distances are, how different our lives are, all those different things we know in my professional work, my family, all those different things,’ a clearly emotional Sanford told The AP, ‘I will be able to die knowing…’ Here the governor broke into heaving sobs before stammering ‘... that I had met my soul mate.’” On July 2, with the media going wild and Republicans wondering why her husband hadn’t just kept his mouth shut, Jenny emailed a statement to reporters calling his behavior “inexcusable” but saying that she would “leave the door open” to the possibility that he would make good on his promise to save their marriage. The couple left with their children for time alone over the July 4 holiday weekend, and the story began to cool. On July 23, Andy Barr of Politico noted that “the governor’s wife was one of the key players in getting some of Sanford’s rivals in the state legislature to temper their calls for his resignation.” If, at the end of June, Mark Sanford looked like toast, a month later he and Jenny looked like they might emerge as the toast of the town—with his governorship, and their marriage, intact. Had that occurred, it’s hard to imagine anyone begrudging Jenny the apparent fulfillment of her prayers. Instead, however, on August 7 Jenny and her four sons moved out of the governor’s mansion into the Sullivan’s Island beach house. She made certain that the press was on hand, and news outlets across the country published photos of her carrying small items away into her truck. Helping her were several women friends, whom she hugged before leaving for good. In a statement issued that day, Jenny continued to speak as if part of a family unit: “I am so thankful for the overwhelming support and prayers we have received from people all across South Carolina. I am literally in awe of how blessed we are to have such love and support from family and friends, old and new.” Still, “after much careful and prayerful consideration,” she saw the only hope of “healing our family” in this marital separation. Once again, she affirmed that “family comes first.” This time, however, it was not clear that Mark Sanford could still be a part of it. Rumors floated in the press that he had refused to break off with his soul mate, but none of the principals would discuss such details. Even conservative religious observers seemed to cheer Jenny on as she stood tall and allowed her marital drama to be played out in public. Part of her support surely came from her professed willingness to work on the marriage if her husband would, but few seemed to be betting on that scenario. The wife who refused submission, who moved out of her husband’s primary residence on national television, was a heroine and a martyr. Feminism had wedged its way into the soft patriarchy of Christian conservatism. Two days after Jenny Sanford’s departure from the governor’s mansion, the AP reported that Mark had used state aircraft for personal trips as well as for political business, contrary to state law. Calls for his impeachment began to stir, and deeper investigations ensued. Without Jenny at his side, the governor had to weather his scandal by himself. As summer turned into fall, his political future remained unclear as Sanford continued to fight “tooth and nail” (his words) against efforts to oust him from office. But whatever the future held, his wife’s finely tuned revision of the old playbook for humiliated political wives was not likely to be soon forgotten. On September 22, Random House announced that she was writing an “inspirational memoir” that would “grapple with the universal issue of maintaining integrity and a sense of self during life’s difficult times.” In the end, the biggest part of the story was the veneration of Jenny Sanford, feminist/evangelical icon of womanly nurturance and dignity. Even if, as some suspected, she turned out to have been an opportunist who played the media brilliantly, she had stood tall and saved her own hide along with her kids. Watching gender play out in religion and politics has never been so much fun. |