|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links: Articles in this issue:

From the Editor: The Open and Affirming Lutherans |

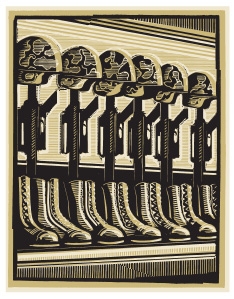

An Army of One

The shooting lasted only about four minutes. But in that brief span, a lone gunman killed 13 and wounded 29 others, before he himself was shot down by base police officers. The shock, grief, and outrage that followed were magnified by the fact that the alleged killer was an Army officer and it appeared that the Army failed to act on solid information that he was an unstable loner who was also a bitter critic of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. That’s about the only common ground that can be found in journalistic reports—and especially interpretations—of the mass killing at Fort Hood November 5. To an unusual degree, attitudes about Major Nidal Malik Hasan’s alleged rampage skewed in two directions, with a great deal of scoffing displayed about those who held alternative views. Interpretation A was that “the Army psychiatrist accused in the shootings acted out under a welter of emotional, ideological, and religious pressures” but was not “part of a terrorist plot,” as a story by David Johnston and Eric Schmitt put it in the November 8 New York Times. It was, in the words of many, “a workplace killing.” Interpretation B focused on Hasan’s Muslim identity and demanded that he be labeled a terrorist. Newsweek quoted conservative columnist Laura Ingraham to this effect on November 10: “What is hard to ignore, now, is the growing derangement on all matters involving terrorism and Muslim sensitivities. Its chief symptoms: a palpitating fear of discomfiting facts and a willingness to discard those facts and embrace the richest possible variety of ludicrous theories as the motives hind an act of Islamic terrorism.” Stories in the first few days after the shootings tended to stress that Hasan was believed to have acted alone. “Investigators have not ruled out the possibility that Major Hasan believed he was carrying out an extremist’s suicide mission,” reported a New York Times story on November 8 that carried the headline, “Little Evidence of Terror Plot in Base Killings.” Rather, the story reported, “investigators, working with behavioral experts, suggested that he might have suffered from emotional problems that were exacerbated by the tensions of his work with veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan who returned home with serious psychiatric problems.” Conservative commentators were particularly inflamed by remarks made by U.S. Army Chief of Staff Gen. George Casey on weekend television news talk shows. Casey expressed concern on CNN’s “State of the Union” November 8, for example, that “speculation about the religious beliefs of Hasan could cause a backlash against some of our Muslim soldiers.” But at this early stage of the story, political leaders, even Republicans, were also urging caution about over-reacting against Muslims. “I mean, does every soldier who shows discontent with the war and every soldier that had had a bad performance report—what are we going to do about these folks,” Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina said the same day on CBS’ “Meet the Press.” “At the end of the day, maybe this is just about him. It’s certainly not about his religion, Islam.” Understandably, not much was known about Hasan in early November. Many news outlets reported that he was born in the United States to recent immigrants from what is now the West Bank but was then part of Jordan. The family moved in the 1980s to Roanoke, Virginia—a working class, Appalachian city in the western mountains of Virginia. There they ran a beer hall and then a chain of restaurants and convenience stores. After high school, Hasan apparently served a term in the Army as an enlisted man, where he began his higher education at a California community college. He returned to Roanoke for more community college before attending Virginia Tech. An outstanding student, Hasan then reenlisted in the Army and was sent to medical school at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences outside Washington. Subsequently, he received training as a psychiatrist at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, becoming one of a number of desperately needed psychiatric specialists in treating soldiers with post-traumatic stress syndrome. In search of information about Hasan, journalists swarmed over Walter Reed. Several also interviewed residents of the shabby apartment complex in Killeen, Texas, where he lived after being re-assigned to Ft. Hood last summer. The Washington Post’s Philip Rucker, for one, reported on November 9 that Hasan was often derided by other residents. Rucker quoted one neighbor as saying residents often laughed at Hasan when he came home from work or the local mosque. “Everyone else just sat down there and laughed and drunk their beer and looked at him and giggled,” the woman said. “They just would laugh at him when he walked down with his Muslim clothes….He was mistreated. He didn’t have nobody. He went to his apartment there and was all alone.” Rucker reported other harassments: In mid August, a drunk soldier who lived down the hall from Hasan scraped a car key down the full length of Hasan’s car and ripped a bumper sticker that read “Allah is Love” off the car. In Virginia, the Roanoke Times reported on November 7 that few remembered Hasan in the city or at the colleges he attended. Those who did, described him as “studious and withdrawn.” About the same time, Julian Barnes and Andrew Zajac of the Los Angeles Times reported that working with soldiers dealing with post-traumatic stress syndrome in recent years had turned him against the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and intensified his Muslim beliefs. Hasan also told relatives in recent years that he was harassed by others in the military for being a Muslim, James Dao reported on November 6 in the New York Times. None of this journalism provided insight from people with more than a passing acquaintance with Hasan. But while it did not paint an unequivocal portrait, by mid-November a coherent analysis was emerging from “the left.” Despite his ethnicity and religion, and even reports of his having shouted “Allahu Akbar” as he began shooting, Hasan’s rampage was “not terrorism,” James Alan Fox and Jack Levin, two criminologists at Northeastern University, wrote in an op-ed column in the November 11 USA Today. “Hasan’s murder spree appears…to be much more about seeking vengeance for personal mistreatment than spreading terror to advance a political agenda. In many respects, the Fort Hood massacre stands as a textbook case of workplace murder,” they wrote. “Fort Hood is indeed a workplace, the U.S. Army an employer, and Hasan a disgruntled worker attempting to avenge perceived unfair treatment on the job. His rampage was selective, not indiscriminate. He chose the location—his workplace—and then apparently singled out certain co-workers for death.” The Fox-Levin analysis turned on Hasan’s alienation in the Army and his failed attempts to leave military service to avoid serving in a war that he perceived as targeting Muslims. “Calling the Ft. Hood ambush an act of terror would only compound the tragedy by reinforcing the kind of intolerance toward American Muslims that appears to have contributed to Hasan’s despair.” This line of reasoning infuriated conservative commentators. Charles Krauthammer took to Fox News to denounce liberals “who want to medicalize Major Hasan’s crime—call it an act of insanity rather than crime.” Jonah Goldberg sneered in the November 12 Chicago Tribune that “for many people, the idea of a Muslim fanatic motivated by other Muslim fanatics was at least initially—too terrible to contemplate.” “How much longer will we tolerate fighting this war as if it were a minor crime wave? Our enemies are fighting to win and they are fighting everywhere, including within our border,” columnist Cal Thomas thundered in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram on November 10. “It is irrelevant that some have put the number of radicalized Muslims worldwide at 10 percent. Even if that figure is accurate, 100 million jihadists can cause a lot of damage.” Writing in the November 10 National Post, Colby Cosh offered the view that “the expectation that Nidal Hasan’s story will fall into one of two bins marked ‘terrorist’ or ‘nutcase’ is, frankly, pretty stupid.” Instead, Cosh offered a both-and analysis. “It may be that the Army bungled its handling of Hasan and that hysterical institutional anti-racism might have gotten 13 people killed,” he wrote. On the other hand, “suicidal terrorists are always troubled misfits….It will almost certainly turn out that Hasan was a quirky loner, that he had social and cognitive problems in school, that he had early and unfixable problems with girls and women.” But “non-Muslims shoot up schools, malls and post offices all the time and it should not be surprising that when a Muslim goes looking for an external locus of blame or rage, his pathology takes a specifically Muslim form.” By the middle of the month, it was the conservative position that began to look more plausible, as scraps of troubling information about the government’s handling of Hasan began to accumulate. One cluster involved official reluctance to take action to address Hasan’s behavior during his time at Walter Reed. Stories began to appear about November 10 with headlines like, “The siren call of Shariah: Ignored warning signs of a radical pathology” (Washington Times); and “Non-believers should have their heads cut off, said army killer. The ‘red flags’ missed before Ford Hood massacre” (London Telegraph); and “In plain sight: Unheeded red flags surround Maj. Nidal M. Hasan” (Washington Post). Stories reported that Hasan had been reprimanded for attempting to convert patients to Islam, that he repeatedly told military colleagues in Washington that he was a Muslim first and an American second, and, most famously, that in 2007 he had given colleagues a startling lecture on the “American war against Islam” during grand rounds at Walter Reed. Usually anonymous sources reported to journalists that fellow officers at Walter Reed had a “fear of appearing discriminatory against a Muslim soldier” and so didn’t file formal complaints. Lt. Col. Val Finnell, who studied at the Uniformed Services University with Hasan in 2007, did complain to superiors. “The system is not doing what it’s supposed to do. He should at least have been confronted about these beliefs, told to cease and desist, and to shape up or ship out. I really questioned his loyalty,” Finnell told the London Telegraph on November 9. The mid-November journalistic narrative was also shaped by the revelation that American intelligence officials had known as early as December 2008 that Hasan was carrying on an email correspondence with an Al Qaeda-connected imam in Yemen, Anwar al-Awlaki. Summarizing information that was appearing in many places, Scott Shane and David Johnston of the New York Times wrote on November 12 that Hasan had sent a dozen or so emails to Awlaki, who had responded several times. The men had known each other, apparently slightly, before 2001, when Awlaki served as imam at a suburban Washington mosque. The imam may have been involved in Hasan’s mother’s funeral in 2001, but left the United States after 9/11. “The emails were largely questions about Islam, not expressions of militancy or hints of a plot,” government officials told Shane and Johnston. “The messages were quickly passed to a Joint Terrorism Task Force in Washington, where a Defense Department investigator pulled the personnel files of Major Hasan,” the Times reported. “Those files, however, did not reflect the concerns of some colleagues at Walter Reed Army Medical Center about Major Hasans’s outspoken opposition to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and his strong feeling that Muslims should not be sent to fight other Muslims.” The Joint Task Force apparently decided that the email correspondence was a legitimate part of Hasan’s academic research and did not pursue the matter by investigating at Walter Reed. The Times then quoted Georgetown University terrorism expert Bruce Hoffman as saying that “any contact with Mr. Awlaki should have raised red flags. There is no doubt that Awlaki is a vessel for the message of Al Qaeda whose goal is radicalizing others. Any contact should have generated serious concerns.” Liberals were reluctant to give up their interpretation, however. Andy Ostroy blogged on the Huffington Post November 16 that it had been “a great week for Republicans—that is if you consider raging hypocrisy and shameless propaganda successful virtues.” A few days later, Robert Wright began an op-ed column in the New York Times with the sarcastic statement that “the verdict had come in” on the liberal media’s coverage of the Hasan case: “The liberal news media have been found guilty—by the conservative news media—of coddling Major Hasan’s religion, Islam.” It was, Wright noted, a continuation of the way the American right and left had reacted to 9/11. “Their respective responses were, to oversimplify a bit: ‘kill the terrorists’ and ‘kill the terrorist meme.’” Not, he continued, that Islamists didn’t have their own caricatures of 9/11 and beyond. In a November 29 column, Thomas Friedman of the New York Times described what he called “The Narrative”—a “cocktail of half-truths, propaganda and outright lies about America that have taken hold in the Arab-Muslim world since 9/11. Propagated by jihadist Web sites, mosque preachers, Arab intellectuals, satellite news stations, and books—and tacitly endorsed by some Arab regimes—this narrative posits that America has declared war on Islam, as part of a grand ‘American-Crusader-Zionist conspiracy’ to keep Muslims down.” “What is scary is that even though he was born, raised, and educated in America, The Narrative still got to Hasan,” Friedman wrote. Time was thinking along similar lines on November 23, asking in a headline “Are lone wolves who don’t need an al-Qaeda training camp the new threat to homeland security?” “I used to argue it was only terrorism if it were part of some identifiable, organized conspiracy,” Georgetown’s Hoffman told Time. “This new strategy of al-Qaeda is to empower and motivate individuals to commit acts of violence completely outside of any chain of command.” Sebastian Rotella of the Los Angeles Times added a third piece to this emerging analysis on December 7, noting that the United States is facing “a rising threat from homegrown extremists.” “There’s radicalization—especially among converts and newcomers,” Zeyno Baran of the Hudson Institute told Rotella. “I think young U.S. Muslims today are as prone to radicalization as Muslims in Europe.” And with that, coverage of the Fort Hood shootings pretty much dropped off the radar screen. In part, this was because the “Islamic terror” spotlight turned to the December 25 “underpants bomber” episode, in part because new information about Hasan stopped appearing, and in part because many people were waiting for the report of an investigation of the Army’s handling of Hasan. That report, co-written by former Chief of Naval Operations Vern Clark and former Army Secretary Togo West and released on January 15, concluded that the military displayed systemic failures, missing the warning signs given by Hasan and failing to share information among its various parts. “It is clear that as a department, we have not done enough to adapt to the evolving domestic internal security threat to American troops and military facilities that has emerged over the past decade,” Defense Secretary Robert Gates told a press conference. “In this area, as in so many others, this department is burdened by 20th century processes and attitudes rooted mostly in the cold war.” “[T]he military,” Gates went on to say, “does not seem alert to signs of radicalization in its own ranks, to be able to detect its symptoms or to understand its causes.” The report suggested that senior officers, especially at Walter Reed, would face disciplinary action. Yet reaction in the press, and especially in the commentariat, was surprisingly restrained. A Washington Post editorial on February 6 emphasized the importance of both taking action to address the problems uncovered in the report and the need “not to go too far.” The Weekly Standard attempted to revive the conservative onslaught with a diatribe on February 1 headlined “See No Evil: The Pentagon’s Fort Hood investigation is a pathetic whitewash.” Penned by Thomas Joscelyn of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, the piece stressed the report’s failure to call Hasan out as a violent jihadist: “The problem is that while many were aware of Hasan’s violent ideological worldview, no one in the military acted on the information because no one wanted to be labeled a bigot.” But that was the loudest outcry from conservatives, whose enthusiasm for criticism of the armed forces tends to be limited. For the liberals, after Fort Hood it seemed harder to insist that radical Islam poses no real threat in the United States, or that the challenge of balancing security and civil liberties in an era of “self-radicalization” is less than daunting. |