|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Table of Contents Winter 2005

Quick Links:

From the Editor: Iraq's Sunni Clergy Enter the Fray The Televangelical Scandal That Wasn't

|

From the

Editor:

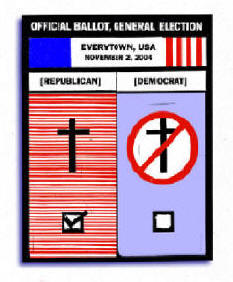

"I've been thinking about you the last day or so, Mark," began my post-election email from the Last Democrat in her suburban Atlanta Church. "You would not believe the 'full court press' that has gone on with all the white churches here in Georgia. I wore my Kerry/Edwards buttons to the mall, to the grocery store, etc. whenever not wearing work or dress clothes every time I even ran into any of the people from my church, they would go into a rant about 'you can't be voting for HIM!,' on and on about how they 'love my Christian President,' etc. Talk about gagging me!" On Election Day, continued Last Democrat, "the church buses were used to go to the high-rise nursing homes all over this part of North DeKalb, load up old people, and bring them to the church to vote. Many were infirm,and under law are allowed to have someone help them in voting. Of course, this someone was one of the church people helping with the buses more than happy to go in and do the touch screen spot for Bush and all Republicans for these poor old people. It just made me nauseous." Well, is this anything for the less partisan among us to be worried about? Back in October of 1980,when the Christian right was a new thing under the sun, the Rev. Jerry Falwell groused to Time magazine that those who were attacking him and his colleagues were hypocrites who had never objected to religion in politics when the perpetrators were clergy supporting liberal causes like civil rights and opposition to the war in Vietnam. "What bothers our critics is that we don't agree with them," Falwell said. Actually, such hypocritical critics were not much in evidence at the time. Even before Falwell's remarks saw the light of day, that icon of liberalism, Harvard law professor Lawrence Tribe, was on record in the New York Times saying, "The tradition of the intermixture of religion and politics is too ingrained in our national life to be eliminated. It is extremely important to the principle of freedom of speech that this process not stop just because some are distressed by the content of the speech or the speaker." And over the years, as the Christian right became ever more deeply ingrained in the Republican Party, the establishmentarian view continued to be that religion and politics mixed reasonably well. When, for example, quasi-clergymen Pat Robertson and Jesse Jackson ran for the presidential nominations of their respective parties in 1988,the Washington Post's chief political bigfoot, David Broder, pronounced,"It's a healthy phenomenon, in the eyes of this secular reporter-critic, and not the menace some see. The clerics sometimes speak uncomfortable truths to the mighty." In the just concluded election cycle, it was harder to be that blithe. The assiduous cultivation of religious constituencies by the Bush apparat, and the undisguised intrusion of evangelical leaders and some conservative Catholic hierarchs into the presidential campaign, demonstrated that the old rule of maintaining a decent respect for the nonpartisanship of religion can now be broken with impunity. On October 23 the determinedly moderate religion columnist for the New York Times, Peter Steinfels, recalled that Alexis de Tocqueville reporting to his compatriots on the state of democracy in Jacksonian America, had called religion "the first of [Americans'] political institutions" even as he pointed out that in the land of the free it kept well clear of electoral politics. "In 2004," wrote Steinfels, "Tocqueville would almost certainly feel that by widespread entanglement in the presidential election, religion has inflicted on itself wounds that will not heal quickly." Maybe so, but up there at his writing desk in the Elysian Fields Tocqueville is more likely fretting over the wounds inflicted by religion on the body politic. Its health was what primarily concerned him, and he intended the American example to show that religion could have a benign impact on a country only by avoiding the kind of political engagement that characterized the Catholic church in France. To be sure, the United States has always had an inclination, not always attractive, to sacralize its business in the world. Without reviewing the history of "city on a hill" and "redeemer nation," suffice it to say that the latest incarnation is President Bush's habit of portraying himself as the instrument of an American mission to bring "God's gift of liberty" to the rest of humankind. Such rhetoric has, at least since the Civil War, mostly served to unify the country. While there have always been those prepared to turn it to partisan purposes, the American civil religion is meant to be inclusive, to unfurl a sacred banner above the political fray. Thus, after World War II, America inserted "under God" in its Pledge of Allegiance and talked promiscuously of "the Judeo-Christian tradition" in order to summon citizens of all religious and political persuasions to common cause against the Communist foe. Presidential elections are, among other things, civil religious exercises in the orderly succession of power, culminating in the oath of office taken with hand on Bible. But over the past quarter century the American civil religion has been invaded by what the Italian scholar Emilio Gentile calls political religion religion as an instrument of domestic political combat. It was Falwell and company who began the now completed process of turning white evangelicals into a solid Republican voting bloc. In 2004 the GOP fully embraced the idea that churches and synagogues of all sorts were where to go for votes. The party's success with religious voters as a whole was brought home this past year by the discovery, via survey data, that the more observant voters are the more likely it is that they will vote Republican, and that the less observant they are the more likely it is that they will vote Democratic. Although journalistic shorthand has tended to use what is only a religion gap to caricature Republicans as pro-religion and Democrats as anti-, there seems little question that the two parties will divide their appeal on these religious lines for the foreseeable future. There have been religious crusades in American politics before. The prohibition of alcohol was one, and the abolition of slavery another. But neither was tied to one political party, and in each it was generally acknowledged that both sides prayed, as Lincoln said, "to the same God," even if they prayed for different things. The civil rights movement, the most successful religious crusade of recent times, traded heavily in the inclusive civil religious rhetoric of Martin Luther King, Jr.,and in Congress depended for its success on the votes of northern Republicans as well as Democrats. Today, in a culture war based on such issues as abortion, same-sex marriage, embryonic stem-cell research, human cloning, and euthanasia (to use the list of "non-negotiable" items in a widely distributed Catholic voter's guide), the religious politics has begun to look suspiciously like what Tocqueville wanted his countrymen to shun. There is the Party of Separation and the Party of Faith -based (or, as a GI in Baghdad told NPR in explaining her vote for Bush): "He's a Christian Republican and I'm a Christian Republican." How odd it is that George W. Bush should be the instrument for bringing French-style political religion to these shores.

|