Exploring the meaning behind the facts of science

by Christine Palm

Few

people associate the word “neuroscience” with a grove of golden mustard

plants growing lustily in an abandoned city lot. But to anyone who knows Hebe

Guardiola-Diaz’s approach to the subject, that’s exactly what might come

to mind.

Few

people associate the word “neuroscience” with a grove of golden mustard

plants growing lustily in an abandoned city lot. But to anyone who knows Hebe

Guardiola-Diaz’s approach to the subject, that’s exactly what might come

to mind.

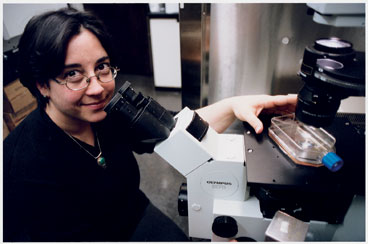

Guardiola-Diaz, an assistant professor of biology and neuroscience, believes her main job lies in instilling in her students not only a love of scientific inquiry, but an understanding of the meaning behind it. A biochemist by training, Guardiola-Diaz is especially interested in the molecular mechanisms responsible for building an intact and functioning nervous system. So how does this lead to three contaminated blocks running between Edwards and Chestnut streets in Hartford’s North End?

When Mary Sherwin, a Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) pollution control expert who lives near Guardiola-Diaz in the city’s West End, came to her with an idea, the professor’s scientific mind clicked into gear.

“I see it as my job to create opportunities for my students to do some good with their scientific aptitude,” she says. “For example, in the summer of 1999 we began to wonder whether a tract of city land contaminated with lead could be rid of its toxicity through phytoremediation, the natural cleansing properties of plants. In collaboration with Professor David Henderson of the chemistry department, we planted mustard plants there. Over the course of several months, our students tended those plants and tested the soil. In the course of doing that, they interacted with neighborhood people who were curious about our experimentation. They met clients from the House of Bread shelter nearby. Eventually, they found that indeed, the lead levels were dramatically reduced. Of course it was an exciting application, but what meant just as much to me was the human growth that paralleled my students’ scientific growth. It was gratifying to see them trouble-shoot instrumentation and optimize analytical methods for determining lead concentration in soil according to Environmental Protection Agency standards. But just as gratifying to me was seeing how, as they grew as scientists, they also grew as human beings.”

Make

no mistake: Guardiola-Diaz is, first and foremost, a molecular biologist. She

laughs self-deprecatingly about the fact that she’s just taken up the piano

again after abandoning lessons as a child in her native Puerto Rico. She makes

no pretense of being a humanist, or an artist, or a philosopher. And yet

listening to her speak of her work, it is hard not to sense the strong

undercurrent of those leanings.

Make

no mistake: Guardiola-Diaz is, first and foremost, a molecular biologist. She

laughs self-deprecatingly about the fact that she’s just taken up the piano

again after abandoning lessons as a child in her native Puerto Rico. She makes

no pretense of being a humanist, or an artist, or a philosopher. And yet

listening to her speak of her work, it is hard not to sense the strong

undercurrent of those leanings.

“Scientific inquiry can, and should, lead to an improvement in the human condition,” she says. “There are many neuro-degenerative diseases that we’ve known about forever—multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s, to name two of the better-known ones. These are extremely severe and debilitating conditions caused by problems at the cellular and molecular level. This is important, because if you understand how neuronal cells develop and function, you can perhaps recapitulate molecular events and develop strategies to help patients cope with their illness. I work on a nuclear protein known as PPAR that may play key roles in the development of oligodendrocytes, brain cells that protect neurons and facilitate communication between nerve cells. We isolate oligodendrocytes from neonatal rat brains and watch them grow and develop. PPAR activators promote their differentiation. We are now identifying genes under PPAR control to gain a better understanding of the role of this protein.”

Along with her students, Guardiola-Diaz has also conducted a great deal of research concerning the recent reappearance of tuberculosis. She has received requests for her papers from scientists and academics from throughout Asia, Europe, and Africa.

“Because of several factors, including the misuse of antibiotics, increased travel, widespread compromised immune systems due to AIDS and other diseases, epidemiologists are finding new strains of antibiotic-resistant TB,” Guardiola-Diaz laments. “And yet, there hasn’t been a single new drug against TB in decades. My students find this outrageous, and I love that they do! There’s no money involved in it for them, and so their research is, in that sense, purely altruistic. But it’s intellectually satisfying, and moreover, it’s right that they should think about someone other than themselves.”

Guardiola-Diaz pauses for a moment as she ponders what she’s just said. She shakes her head and laughs. “I guess I sound a bit like I’m giving a sermon, but honestly, applied science goes to the essence of what it means to be human,” she says. “I’ve been close to a few people with serious mood disorders, and I’ve always been curious about why the brain works differently in different people. What I find beautiful about it is celebrating individuality and acknowledging a wide spectrum of behavior, ability, and talent. What concerns me is when those brain patterns lead across boundaries into territory that is debilitating and isolating.”

What strikes a visitor to Guardiola-Diaz’s busy office in the Life Sciences Center is that she manages, somehow, to integrate so many various aspects of her life. She and her husband Alfin Vaz, a scientist with Pfizer, are the parents of three-year-old Uma, and will soon be adopting another daughter, from India. A native of Puerto Rico, she chose to do her post-doctoral fellowship at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. She did her graduate work in biological chemistry at the University of Michigan, and has taught at Trinity since the fall of 1998. Her phone rings nearly non-stop, and the callers alternate between the guy fixing her car and a former student reporting excitedly that she met a “scientific guru” at a conference and, thanks to Guardiola-Diaz’s class, was able to talk at length about the detoxifying properties of plants.

“I care very much that the next generation of scientists is more than a group of well-educated technocrats,” she says. “I want them to explore the meaning behind the facts, to really participate in their own education, and to practice science with a purpose.”